Dwarf planet Ceres is rich with ice and once might have supported life, scientists say

The research gives hope that we one day might mine asteroids for water and use Ceres as a base for our explanation of the solar system

A dwarf planet in our own solar system might once have supported life, scientists have said.

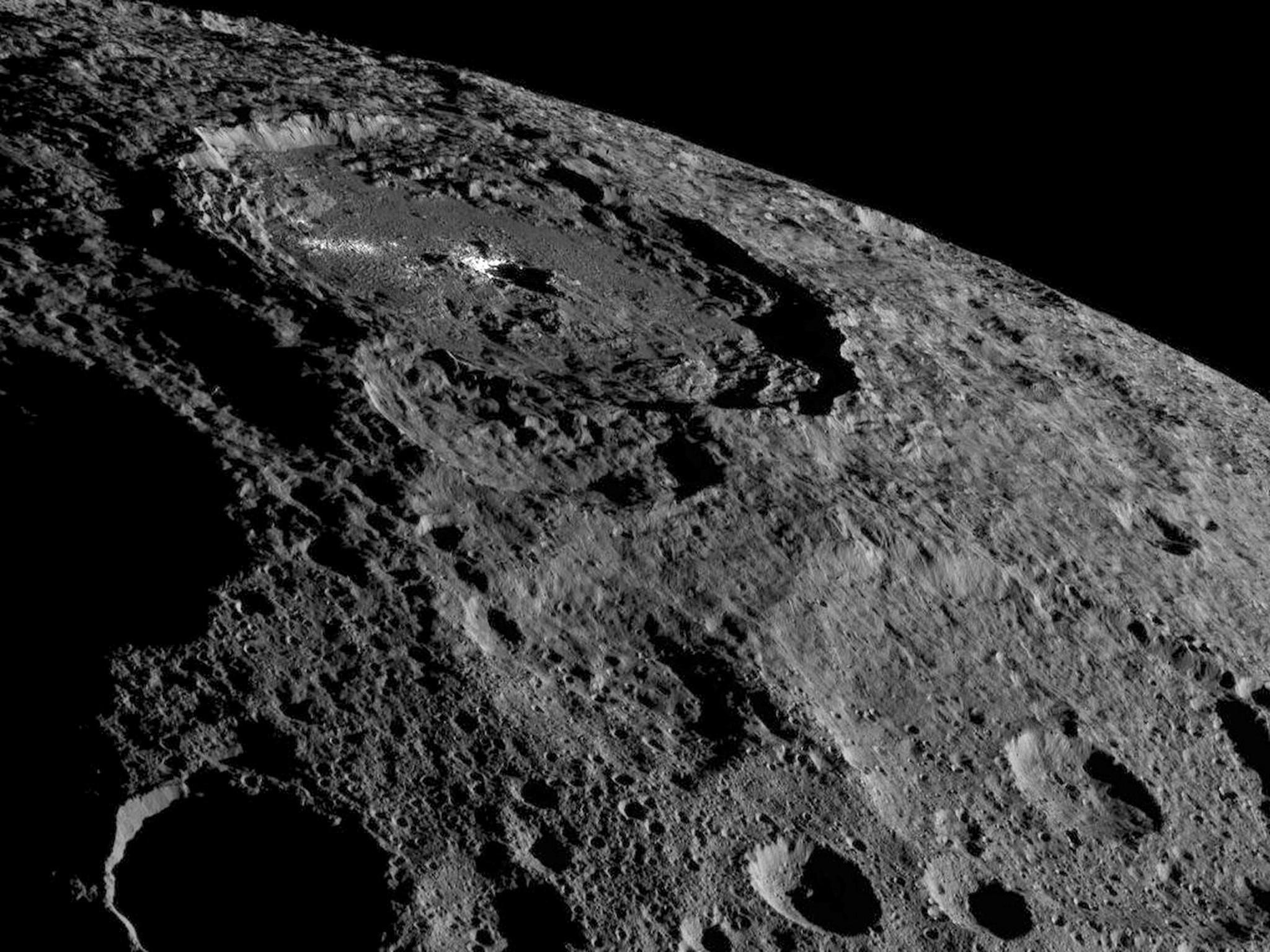

Ceres, a mysterious rocky planet in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, has a rich body of ice beneath its dark surface, according to scientists.

The discoveries were reported in a pair of studies published in the journals Science and Nature Astronomy. The scientists behind them hope that they could help commercial endeavours to mine water and other resources from asteroids, and to send humans out beyond the moon.

The water could even be a hint that there was once life on the dwarf planet’s briny surface, according to the researchers.

The studies show that Ceres is about 10 percent water, now frozen into ice, according to physicist Thomas Prettyman of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, one of the researchers.

Examining the makeup of solar system objects like Ceres provides insight into how the solar system formed. Compared to dry Vesta, Ceres is more like Enceladus and Europa, icy moons of the giant gas planets Saturn and Jupiter respectively, than Earth and the other terrestrial planets Mercury, Venus and Mars, Prettyman added.

Scientists are debating if Ceres hides a briny liquid ocean, a prospect that may put the dwarf planet on the growing list of worlds beyond the solar system that may be suitable for life, said Dawn deputy lead scientist Carol Raymond of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

"By finding bodies that were water-rich in the distant past, we can discover clues as to where life may have existed in the early solar system," Raymond said in a statement.

The finding strengthens the case for the presence of near-surface water ice on other bodies in the main asteroid belt, Prettyman said.

Information collected by Dawn showed that Ceres, unlike Vesta, has been using water to create minerals. Scientists combine mineralogical data with computer models to learn about its interior.

"Liquid water had to be in the interior of Ceres in order for us to see what's on the surface," Prettyman told a news conference at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco.

Additional reporting by Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks