The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Scientists accidentally discover a material that can ‘remember’ like a brain

Discovery could enhance capacity, speed and ultimately lead to the miniaturisation of electronics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have discovered the first-ever physical material capable of “remembering” its entire history of physical stimuli, similar to that of a brain.

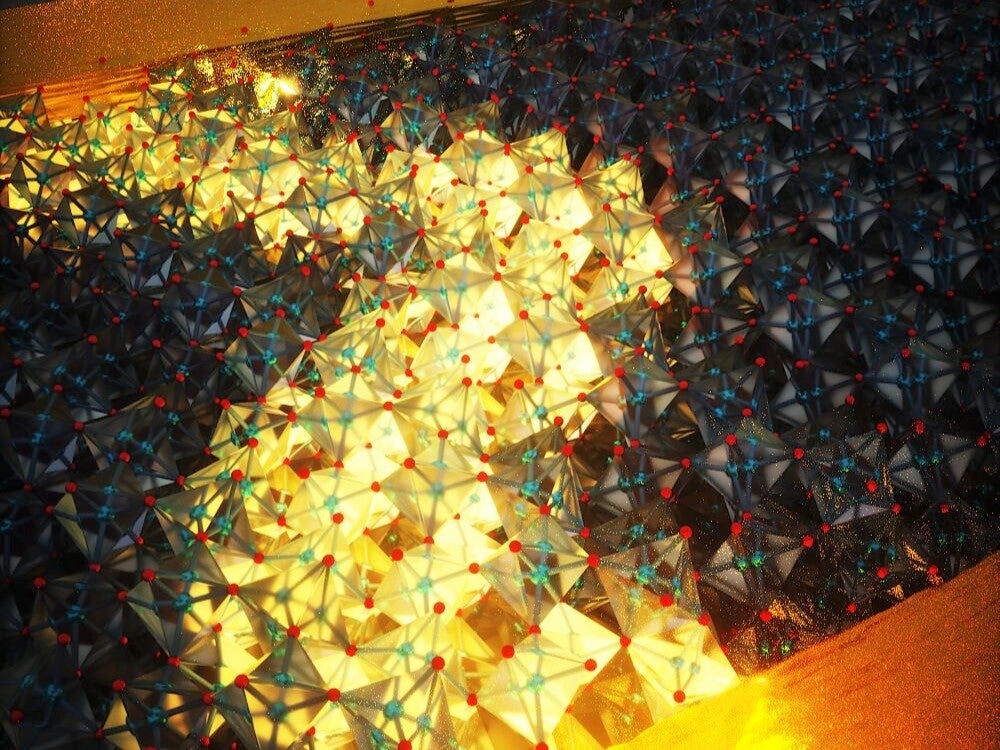

The team from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland stumbled upon the remarkable property while researching phase transitions of vanadium dioxide (VO2), a compound used in electronics.

PhD student Mohammad Samizadeh Nikoo was attempting to figure out how long it takes for VO2 to transition from one state to another, but soon realised that something never before seen was happening when an electric current was applied.

“The current moved across the material, following a path until it exited on the other side,” Mr Samizadeh Nikoo said.

“As the current heated up the sample, it caused the VO2 to change state. And once the current had passed, the material returned to its initial state.”

After applying a second electrical current during the experiment, the researcher observed that the time taken for the material to change state appeared to be directly related to its history.

“The VO2 seemed to ‘remember’ the first phase transition and anticipate the next,” said Professor Elison Matioli, who supervised the research.

“We didn’t expect to see this kind of memory effect, and it has nothing to do with electronic states but rather with the physical structure of the material. It’s a novel discovery: no other material behaves in this way.”

The discovery could have major implications for advancements in electronics that rely on memory to perform calculations.

By having the memory effect be an innate property of the material itself, the researchers claim it could enhance the capacity, speed and, ultimately, the miniaturisation of electronics.

A study detailing the research was published in the scientific journal Nature Electronics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments