Paralysed man communicates first words in months using brain implant: ‘I want a beer’

Locked-in ALS patient also asked to listen to Tool ‘loud’ and ordered a curry

A completely paralysed man, who was left unable to communicate for months after losing the ability to even move his eyes, has used a brain implant to ask his caregivers for a beer.

Composing sentences at a rate of just one character per minute, the man also asked to listen to the band Tool “loud”, requested a head massage from his mother, and ordered a curry – all through the power of thought.

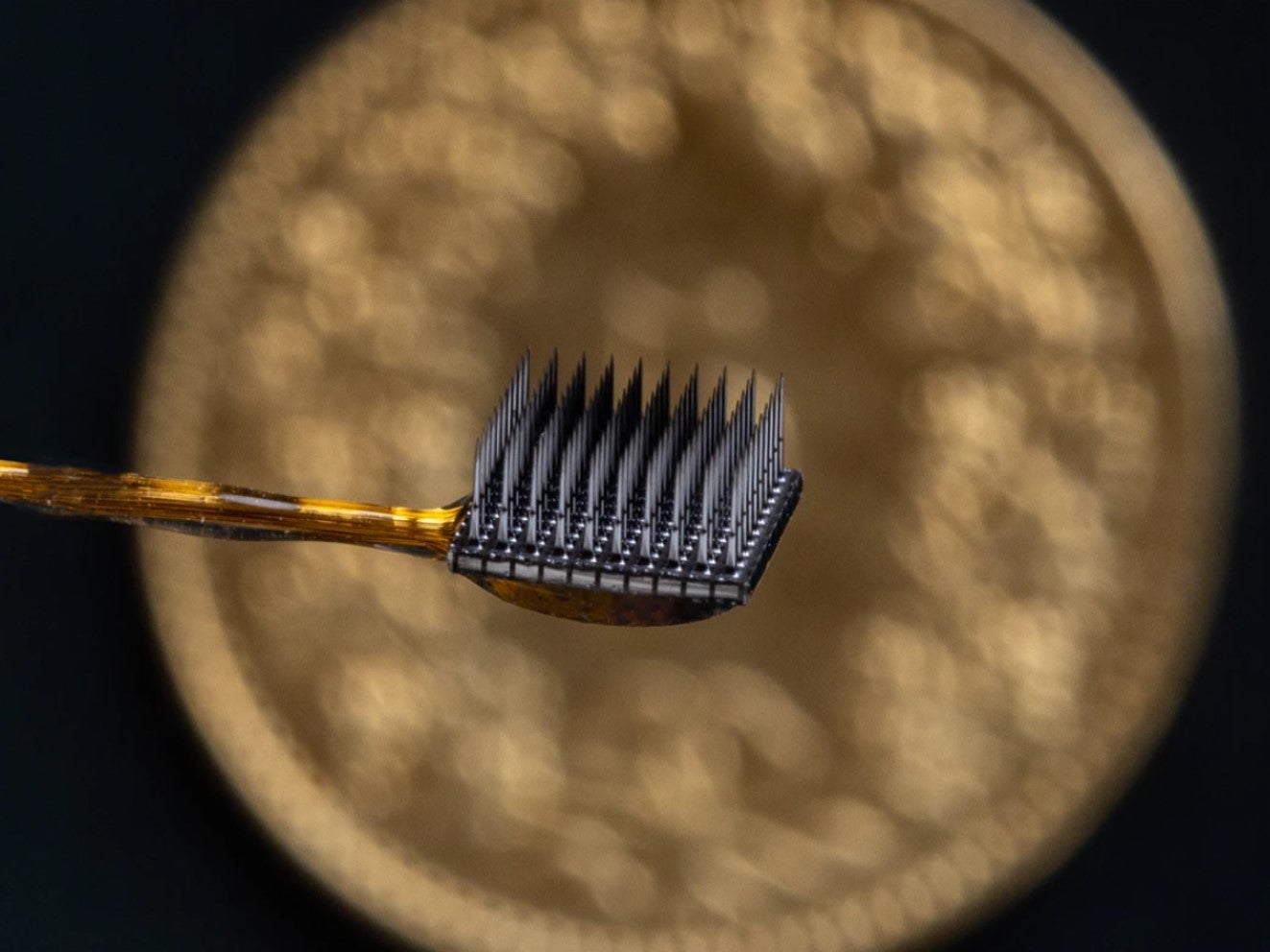

The man, who is now 36, had two square electrode arrays surgically implanted into his brain to facilitate communication in March 2019 after being left in a locked-in state as a result of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

People suffering from the progressive neurodegenerative disease have an average life expectancy after diagnosis of two to five years, though they can live much longer. (The late physicist Stephen Hawking lived another 55 years after his diagnosis, relying towards the end of his life on a communication device controlled by a single cheek muscle.)

Until now, a brain implant has not been tested on a completely locked-in patient, and it was not known whether communication was even possible for people who had lost all voluntary muscular control.

“Ours is the first study to achieve communication by someone who has no remaining voluntary movement and hence for whom the BCI is now the sole means of communication,” said Dr Jonas Zimmermann, a senior neuroscientist at the Wyss Center.

“This study answers a long-standing question about whether people with complete locked-in syndrome – who have lost all voluntary muscle control, including movement of the eyes or mouth – also lose the ability of their brain to generate commands for communication.”

Working with researchers at the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering in Geneva, Switzerland, the ALS patient consented to having the brain implant fitted when he still had the ability to use eye movement to communicate in 2018.

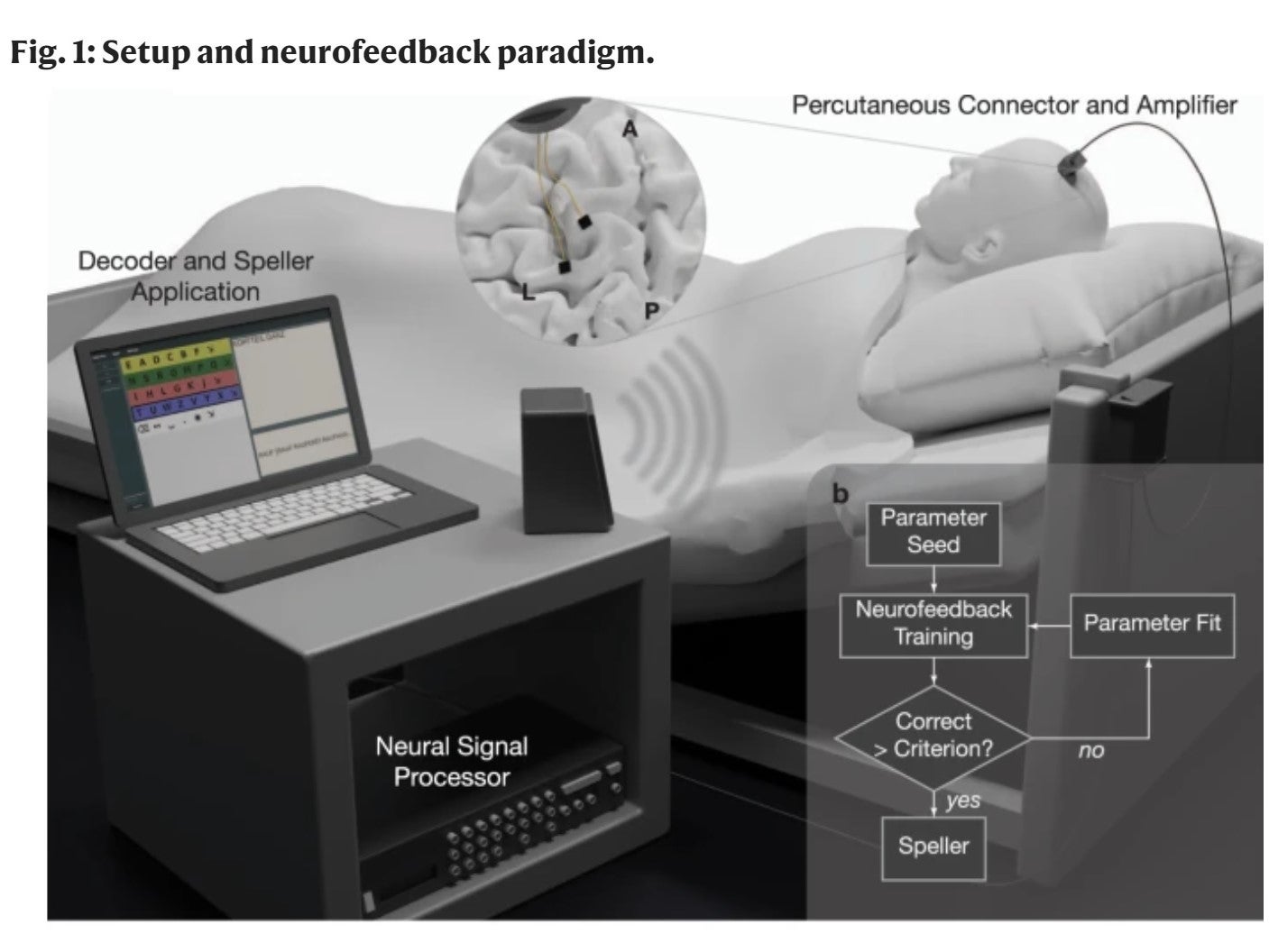

It took three months of unsuccessful attempts before a configuration was achieved that allowed the patient to use brain signals to produce a binary response to a speller program, answering ‘yes’ or ‘no’ when presented with letters.

It took another three weeks to produce the first sentences, and over the next year the patient produced dozens of sentences.

One of his earliest communications concerned his care, asking for his head to be kept in an elevated and straight position when there were visitors in the room.

He also requested different kinds of food to be fed through his tubes, including goulash soup and sweet pea soup. “For food I want to have curry with potato then Bolognese and potato soup,” one request stated.

He was also able to interact with his 4-year-old son and wife, generating the message: “I love my cool son.”

The research was detailed in a study published this week in the journal Nature Communications.

The study, titled ‘Spelling interface using intracortical signals in a completely locked-in patient enabled via auditory neurofeedback training’, noted that the BCI communication system can be used in a patient’s home, with some sessions even being performed remotely via the patient’s laptop.

The scientists behind the brain-computer interface technology are now seeking funding to provide similar implants for other people with ALS, which will cost close to $500,000 over the first two years of use.

“This is an important step for people living with ALS who are being cared for outside the hospital environment,” said George Kouvas, chief technology officer at the Wyss Center.

“This technology, benefiting a patient and his family in their own environment, is a great example of how technological advances in the BCI field can be translated to create direct impact.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments