Beware the ghost of emails past

The permanence of electronic mail is highlighted by the hacking scandal at the News of the World. Why do so many of us use our office address for gossip, shopping and other, darker, deeds? We hit the send button at our peril, argues Rhodri Marsden

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Emails are quick to rattle off and ridiculously easy to send. If this wasn't already manifestly obvious, try going on holiday for a fortnight, come back, check your emails and witness the avalanche of slurry that slides inexorably into your inbox. Actually, perhaps emails are far too easy to send; maybe they should require us to complete some onerous physical task before the server is prepared to deliver them.

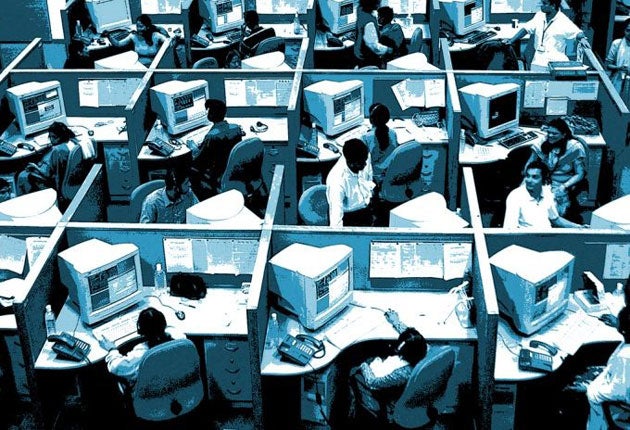

The medium often stands accused of being inefficient, unhelpful, of presenting us with too much of the wrong kind of information, and also erecting a kind of depersonalised barrier behind which we all feverishly type without thinking. It gives us carte blanche to present ourselves as, say, forceful, demanding individuals, when in reality we're simpering yes-men who are terrified of causing offence. Brutally aware of this, various companies will proudly announce a "No-Email Day", hoping to inspire employees to enjoy a more human way of communicating.

But we can't leave emails alone, not now. As soon as No-Email Day is over, we dive straight back in. It's too convenient to abandon, its most obvious advantage in the workplace being its talent for proving you said something (or didn't say something) whenever a dispute arises. It's there, all in black and white. You cover your back, and they can't deny it. And thanks to a raft of data-protection legislation, your company email account is a permanent, ever-expanding data-trove, providing an incredibly useful record of who said what and to whom. Millions of virtual conversations can be stored in an easily searchable database on a disk the size of the palm of your hand.

But... there are so many buts. We sometimes have off days at work; in fact, your emails may reveal more off days than on days. If we were presented, This Is Your Life-style, with the contents of our "Sent Mail" box over the past few years, we'd inevitably wince at the way we dealt with certain issues. We'd regret dashing off a vaguely abusive two-liner to a client that irritated us. We'd regretfully suck through our teeth at that habit we had of suffixing every email to our boss with a smiley, winking emoticon with a big nose – ;0) – to give the impression that we were having a delightful time in their employ. The speed and informality of emails coupled with their permanence is, actually, pretty dangerous. There's no way we'd want our performance at work to be judged by the emails that we send – but it can happen, and we forget that it can happen.

When senior executives at the News of the World exchanged emails during the height of its journalists' phone-tapping activity, the notion that that data might be conveniently preserved for reading by investigators five years hence probably didn't occur to them. But after a claim last December that the crucial chunk of said emails had been "lost" in a transfer of their back-up system to India, it turns out they're in the UK after all. The people who sent them will have barely any recollection of them; might there be the odd cold sweat over what their examination could reveal?

If you have an office-based job and you're at work now, just as an experiment, have a look at your email folders. You might find confirmations of online shopping sprees you've done with various retailers. There'll undoubtedly be a sprinkling of personal communications covering non-work topics, both with your colleagues and with your friends in other buildings. There might be Facebook notifications, extended bitching about the boss or links to semi-amusing YouTube videos. But if you find yourself experiencing twin rushes of guilt and shame and you're now stabbing furiously at the "delete" button, there's no real point. They're probably already stored, somewhere, because your employer is obliged to have them so. And while you might get away with a stern warning if all the above were discovered and you were hauled out of your chair for a disciplinary, it's a curious thing about our propensity to misuse work emails that we simply carry on doing it. Many email howlers have passed into folklore, but our amusement at other people's misfortunes doesn't seem to stop our own indiscretions.

You have to understand – and you probably do, but just ponder it again for a moment – that if you send an email with even mildly eyebrow-raising content from your work machine, you have absolutely no control over its eventual distribution. If you're fortunate, it might sit on a server for eternity and never be seen again, but if luck's not swinging your way, it could be forwarded around the world in minutes, appended with a whole series of comments from disbelieving strangers.

Sexual revelations are a common theme running through the worst work email disasters; the names of Claire Swire, Peter Chung and Patrick Smith will for ever be associated with their sexual preferences for those of us who saw those famous emails, and those who didn't can find out instantly what they were by using a search engine.

Others, such as Lucy Gao, found themselves mocked simply for being a bit confused and socially gauche. Lucy sent a ridiculous email detailing the exact behaviour she expected from attendees to her 21st birthday party ("The more upper class you dress, the less likely you shall be denied entry" was one glorious example) but she made it a whole heap worse by sending it from her Citigroup email account. If she'd sent it from Yahoo!, it would never have made such headlines and hung around in our collective consciousness. But her haughty, wannabe attitude became instantly associated with Citigroup, and she became one of a colossal list of people who have either been disciplined or dismissed for "inappropriate use of the email system". Meanwhile, bosses, legal advisers and IT departments continue to rack their brains to work out a way of stopping such PR disasters (or, indeed, legal disasters) from happening again.

But you can't stop it. The weapons that companies have at their disposal are feeble and almost completely ineffective – one of them being the email disclaimer. This lengthy tract of prose typically sits underneath any email that's sent or received from a corporation, and says something along the lines of "The information within this email is confidential and intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use or disseminate the information contained in this email."

There's a glaring problem with this straight away: once I've read the text telling me that I might not be allowed to read the email, I will have already read the email. If I'm not the intended recipient, why was the email addressed to me? And what power, exactly, do you have to stop me forwarding this email if I don't even work for your company? The disclaimer typically goes on to say that "Any views expressed in this message are those of the individual sender"; that's all very well, but an eye-popping work email that ends up going viral will for ever be associated with the company, regardless. Attempts at enforcing confidentiality start to lose some of their efficacy when an email is spinning its way around the planet suffixed with LOLs. And, in any case, these disclaimers have no legal authority; they've simply never been tested in court. Their only real purpose is to add about three pointless sheets of paper to a printout of any email.

Another, perhaps more ominous, addendum to our work emails is the casual mention that we might be being watched "for staff training purposes" or similar. Your IT department may well have access to your email account for maintenance reasons; it's unlikely that they'd be remotely interested in your purchase of two tickets to see Black Swan, but they could probably find out if they wanted to. Larger-scale monitoring of email content – which undoubtedly goes on – is much harder for companies to do in a way that's proportionate to the risks posed by unauthorised use and that doesn't breach data-protection legislation.

Years ago, when I was working for a book company, I was taken to one side and told that I couldn't send external emails outside the building any longer because their traffic reports indicated that I was sending way too many. And a cursory scan of the subject lines and recipients revealed that the content had less to do with books and more to do with the aftermath of a cataclysmic relationship breakdown. I had been warned that my emails could be monitored, but a glance at the Telecommunications (Lawful Business Practice) (Interception of Communications) Regulations reveals that said regulations don't cover personal communication. In other words, if companies read any emails I send from work that contain personal content, that's unlawful – but how do they know until they open them? It's a legal minefield that pits employees' rights against employers' rights in a vague soup of contradicting legislation. If we've used work emails to mete out abuse to someone, we should expect to get fired. But if we feel that our email has been scoured by the boss purely in order to find a reason for them to sack us, that's a different story.

Anyone who's pondered this issue for more than a minute or two will already have restricted their use of work emails to business matters only, and adopted the view that they should only say things in work emails that they'd be happy for the whole organisation to see. For anything personal, they'd fire up Gmail or Hotmail instead. But it's not merely the things we say in these personal emails; it's the time that's being taken out of our working day to say them. Employers understandably hate our wasting time at work, and construct lengthy "internet acceptable use" policies – including bans on webmail in some cases – in an attempt to stamp out inappropriate activity during paid time. Banning personal phone calls at work could be seen as violating employees' human rights, and forbidding discussion of last night's X Factor with a colleague would surely transform a workplace into a sweatshop. But email communication, because of all its attributes – easy, simple, efficient, monitorable, permanent – is always going to be looked at more sternly.

Then there's use of the web – always a thorny issue with employers, initially because of the mass of not-safe-for-work content, but latterly because of the rise of social networking, with Facebook or Twitter providing a permanent online social playground in a browser window. So these sites get blocked, but the choice of some of the websites that companies make inaccessible seems disproportionately draconian. Some don't even let you read the Daily Express, for goodness' sake. A friend of mine told me that access to job-seeking websites was banned at a former workplace, and automatic email searches for the word "CV" would instantly bring to the attention of bosses any employee's attempts to leave the evil clutches of the organisation.

An employee who has their personal-communication opportunities restricted isn't a happy employee, according to a survey carried out 18 months ago by email provider GMX. "Access to personal email is a valuable way for workers to relieve the negative effects of work," it concluded. But do we have any right to complain if we feel we're being treated unfairly? A friend of mine who for years railed against the harsh nature of companies' internet policies had a complete change of heart when he started to work in an IT department and witnessed the incredible level of abuse we subject their systems to. And we're in denial about it; one survey showed that we admitted to, on average, 40 minutes of personal internet use per week at work. Per week? 40 minutes? Per week? Seriously?

The sophistication of modern smartphones shifts the whole issue, of course. Pinging messages backwards and forwards with friends is easier than ever. As they aren't going through the companies' servers, corporate blushes will be spared if we say anything out of line. But as far as wasting company time is concerned, that's much harder to eradicate – unless, of course, employees are frisked for their phones at reception.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments