Alex Garland's film Ex Machina explores the limits of artificial intelligence - but how close are we to machines outsmarting man?

Having watched the new film, Rhodri Marsden found himself celebrating the joys of humanity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.My girlfriend casually informed me, apropos of nothing, that she'd washed her hair using shower gel rather than shampoo. I raised an eyebrow. "Well, I guess it's all the same," I said. "It's all detergent, isn't it? Shampoo, shower gel…" "Cillit Bang," she added, prompting 30 seconds of sporadic giggling at the very idea. At that moment, I could be pretty certain that neither of us were robots. Such exchanges feel like the essence of being human: unpredictable behaviour, saying things that don't need saying, reaching absurd conclusions and experiencing joy as a consequence. Good times.

In the film Ex Machina, released this week, a young coder finds himself in the company of an attractive robotic female entity named Ava, built by his boss. The film's narrative hangs around the apparent self-awareness possessed by Ava; at times, it's evident that she passes the Turing Test, the term given to the various ways in which artificial intelligence (AI) is measured against that of humans.

But is Ava actually experiencing consciousness? Can she feel? Is she capable of making light-hearted quips about bathroom cleaner and enjoying the reaction said quip prompts in others? Many scientists doubt, even given the extraordinary advances in technology awaiting us, that AI can realistically match the combined intelligence and consciousness of human beings. Others believe fervently that it can, and that it poses profound questions for the future of humanity. That moment of attainment is known as The Singularity.

One of the inherent difficulties of debating The Singularity is that humans are incapable of predicting the nature of an intellect that will exceed our own. We have no real idea of what The Singularity means for us. That doesn't, of course, stop scientists, radical thinkers, philosophers and AI experts making best guesses, and their visions range from the utopian to the hellish.

Ray Kurzweil, Google's director of engineering and the man perhaps most closely associated with The Singularity term, is almost evangelical in his optimism. He excitedly outlines a vision of the future where man and machine combine, extending our lifespans indefinitely and making optimum use of everything around us. Science fiction writers and film-makers have, over the years, sounded a more cautious note in the interest of dramatic tension.

Some scientists, meanwhile, warn that any entity with greater intelligence than ours is unlikely to have our best interests at heart. "If we're lucky, they'll treat us as pets," says Dr. Paul Saffo of Stanford University in The Singularity, a documentary film by Doug Wolens. "If we're very unlucky, they'll treat us as food."

The speed at which The Singularity is approaching is, according to Kurzweil, driven by the nature of the growth in technological power – "exponentials" – in relation to our own relatively static intelligence. For example, Moore's Law, formulated in 1965 by the co-founder of Intel, Gordon Moore, broadly states that computer speed doubles every two years, and that's still holding true.

Some argue that the overall rate of growth is slowing, some say it's speeding up, but there's enough confidence knocking about for a few dates to have been assigned to The Singularity.

Kurzweil pegs it to the year 2045, by which time he believes that one computer will possess equivalent intelligence to every human being on the planet combined. These kinds of comparisons, however, rely on the assumption that the brain can be represented in terms of computing hardware – a philosophy known as Strong AI.

Advocates say there's nothing intrinsically special about living matter that prevents it from being modelled; the brain, after all, processes inputs, delivers outputs and possesses memory – though, yes, with somewhere approaching 100 billion neurons in a human brain and more possible connections than there are atoms in the universe, that would be a formidable computational task. However, that task is made even more complex by those thorny questions of sentience, self-awareness and consciousness, described by Sir Nigel Shadbolt, professor of artificial intelligence at the University of Southampton, as the "Hard Problem".

"We have no idea how much sentience has to do with being ensnared in the body we have," he says. "We can't even come to an agreement about where, in the evolution of actual organic life, anything like self-awareness kicks in. We're building super-smart micro-intelligences – we call them AI – that can recognise your face, translate from one language to another, learn to play games and get better at them. But we have no clue about what a general theory of intelligence is, let alone self-awareness. Why, come 2045, that should that suddenly change... I don't think that matching the processing power of the computer to the brain is going to give us any better insight."

Mark Bishop, professor of cognitive computing at Goldsmiths, is on the same side. "If you accept the premise that everything about the brain is explainable by a computer program," he says, "then Kurzweil is absolutely right. But I believe that there are many strong grounds for doubting that claim. No matter how good the AI, the computer will never genuinely understand. It might appear to, but only in the sense that a small child might appear to understand an adult's joke when it laughs appropriately at a dinner party."

Bishop outlines three arguments that address the question of consciousness and computing. The first, by John Searle, dates from 1980 and is known as the Chinese Room; if a computer convinces a Chinese speaker that it understands Chinese by responding perfectly to their questions, it has passed the Turing Test. But does it really understand Chinese, or does it only simulate understanding? The second is Bishop's own argument from his 2002 paper, Dancing With Pixies. "If it's the case that an execution of a computer program instantiates what it feels like to be human," he says, "experiencing pain, smelling the beautiful perfume of a long-lost lover – then phenomenal consciousness must be everywhere. In a cup of tea, in the chair you're sitting on."

This philosophical position – known as "panpsychism" – that all physical entities have mental attributes, is one that Bishop sees as Strong AI's absurd conclusion. Shadbolt agrees. "Exponentials have delivered remarkable capability," he says, "but none of that remarkable capability is sitting there reflecting on what very dull creatures we are. Not even slightly."

The third argument Bishop makes is that there's something about human creativity that computers just don't get. While a computer program can compose new scores in the style of JS Bach, that sound plausibly like Bach compositions, it doesn't design a whole new style of composition. "It might create paintings in the style of Monet," he says, "but it couldn't come up with, say, Duchamp's urinal. It isn't clear to me at all where that degree of computational creativity can come from."

By contrast, one of the scientific advisers for Ex Machina, geneticist Adam Rutherford, describes the consciousness of Ava's character as being a mere "couple of conceptual breakthroughs" away. So it's evident that there's profound disagreement and some deeply entrenched opinions about the likelihood, let alone the timing, of The Singularity. Kurzweil rejects the views of many of his critics, saying that they can't comprehend the exponential rate of technological change, and those who subscribe to his views dismiss counter-arguments as being weighed down by religious baggage. However, ironically, Kurzweil's vision of eternal life (where realigning misaligned molecules can prevent disease, and where we can be physically augmented by technology) almost seems to be driven by a semi-religious instinct – specifically, a fear of death.

"People who reject religion are often very scared of death," says Bishop. "It seems there's a deep lack, and some people replace that by buying uncritically into a computational dream, a dream of robot minds and silicon heaven."

Bishop also stresses that there are emergent ways of looking at the problem of consciousness that bypass that dream. "The dominant metaphor for the mind over the past 50 years has been the computer, but there are many exciting new avenues where scientists are looking at the way consciousness arises without buying into this computational metaphor – which, in my view, has had its time."

The Singularity and its consequences are almost inevitably addressed in the media with slightly hysterical overtones. When the co-founder of Paypal, Elon Musk, recently donated $10m (£6.6m) towards research into the safety of AI, it was described in one newspaper as a move to "prevent a robot uprising". And while a post-Singularity world is by its very nature unfathomable, Shadbolt stresses the need for care, even among those who don't believe in the concept.

"There are lots of ways of being smart that aren't smart like us," he says. "A robot doesn't have to have self-awareness to be autonomous and capable of creating havoc. It's right to come out and say, for example, that you shouldn't build a self-replicating, single-mission system." Philosopher Nick Bostrom outlined one such system: a superintelligence whose goal is the manufacture of paperclips. Let loose, it would have no reason not to transform the solar system into a giant paperclip manufacturing facility.

"And I'd suggest," laughs Shadbolt, "that Earth would be a duller place as a result."

The arguments surrounding The Singularity are deeply compelling, not least because they ask us to assess what it means to be human. In a landmark essay for Wired magazine in 2000, Bill Joy, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, wrote a heartfelt and somewhat anxious response to Kurzweil's vision, during which he recalled the penultimate scene in Woody Allen's film, Manhattan. Allen considers why life is worth living: for him, it's Groucho Marx, the second movement of the Jupiter Symphony, Swedish movies, the crabs at Sam Wo's and so on.

"Each of us has our precious things," wrote Joy, "and as we care for them we locate the essence of our humanity."

I briefly glimpsed my own humanity in a joke about washing one's hair using Cillit Bang – and unlike The Singularity, it was a very small thing. But maybe it's the small things, not the big ones, that are most important.

'Ex Machina' is on general release from today

The top 5 AI movies

Blade Runner

In Ridley Scott's film, based on Philip K Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the "replicants" are implanted with false memories to make them think they are human. One question: is Harrison Ford among them?

2001: A Space Odyssey

HAL 9000 is the computer that controls the Discovery One on a mission to Jupiter in Stanley Kubrick's classic. HAL's monotone is surely one of the creepiest AI voices in film history, becoming particularly menacing when the system turns on the crew.

The Terminator

Arnold Schwarzenegger's cyborg assassin is indistinguishable from humans (apart from the metal interior, that is). But the dogs are on to him.

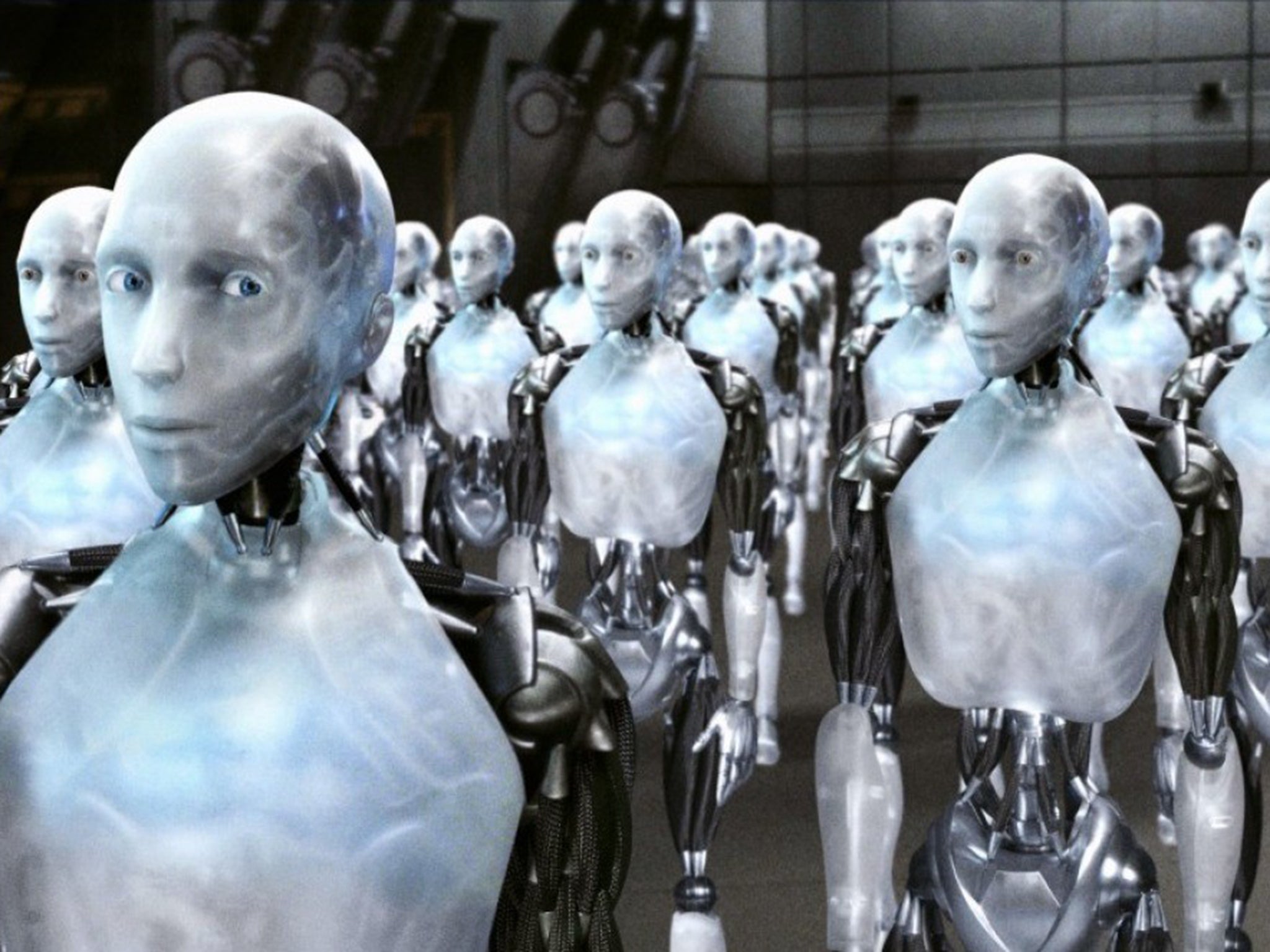

I, Robot

All the robots in this Will Smith blockbuster, set in 2035, are programmed with the Three Laws of Robotics, meaning that they can never harm, and must always obey, humans. But then one robot, Sonny, decides to go rogue.

Her

Scarlett Johansson's husky voice brings Samantha, a Siri-esque computer operating system with accelerated learning capabilities, to life. Joaquin Phoenix's Theodore gets in too deep with the sexy construct he has brought in to organise his emails.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments