Aids and Covid-19: A life lived between two pandemics

As we enter the second year of the pandemic, Robin Gorna reflects on how her life has been shaped by pandemics over the past 50 years

New epidemics demand humility, curiosity and hope. On 5 June 1981, the US Centre for Disease Control (CDC) published its first report of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in five gay men in Los Angeles, California; on 5 January 2020 the World Health Organisation (WHO) published its first report of pneumonia of unknown cause in 44 patents in Wuhan, China.

As we move into the second miserable year of the new pandemic, we also hit the fifth decade of the one where I did my growing up. My life continues to be endlessly changed by these different, and in some ways oddly similar, pandemics. Some of the responses to Covid build brilliantly on the lessons of the past, other aspects should. From the beginning I was fascinated by this rapidly emerging new epidemic, and the similarities of science, politics and people with what I experienced decades ago. Then in May 2020 – late in the first wave – I became sick with Covid-19. As my own infection lingered, so did my focus on the connections and differences, and the lessons we still might have time to learn, from global and local responses to Aids.

Five years after that first pandemic started, I found myself on the barricades caught up in the excitement of volunteering for the Terrence Higgins Trust (THT). An enthusiastic, idealistic student, I learned so much from extraordinary men (mostly) whose activism was grounded in the global struggle for gay rights. A huge amount of energy for change came from people living with HIV and Aids, like the UK’s (mostly now disbanded) support groups Frontliners, Positively Women and Blackliners.

People joined them searching for information and solidarity, then quickly shifted gear to advocacy, confronting neglect and lack of services. Their enraged and focused energy shaped and inspired my sense of how change happens. United by a shared awareness of risk, and horror at the demonisation of the sick and dying, Aids attracted keenly committed volunteers and brilliant advocates at all levels of the response. It’s not been the same with Covid.

Invisible for too long, and often fearful of racist repercussions, African and Caribbean communities were also disproportionately affected by that virus

Failing to recover from my Covid symptoms, I searched online for support from others and, finding virtual groups bringing together thousands of people, I soon started to share what I’d learned from the other pandemic of my lifetime. The Aids rallying cry “Nothing About Us Without Us” struck a chord with other people living with Long Covid. In August 2020, I joined some of them to give evidence to the UK’s All Party Parliamentary Group on Covid and subsequently drafted a long list of demands that we sent to the Health and Social Care Committee. The committee quizzed health secretary Matt Hancock about non-existent services; he rapidly announced £10m to set up Long Covid clinics. Sounds good – but currently there are 1 million people with Long Covid in the UK (according to the ONS) . It’s a paltry £10 per person .

Many of us are enraged by the consequences of underfunding: extreme waiting lists, inadequate care, inept information campaigns and much besides. Yet unlike Aids, no dynamic activist force for change has emerged. Why? It doesn’t help that profound fatigue is the defining symptom of Long Covid. Also, few of us were connected before our Covid symptoms lingered – except the hundreds of thousands of health and care workers (ONS recently discovered that – unsurprisingly – they carry the highest burden of Long Covid). It’s shocking to watch the neglect of so many who suffer from long-term symptoms after getting sick at work – people, especially from black and Asian communities, infected due to inadequate PPE and often forced back to work too early or retired against their will, rather than supported with a phased return. As midwife Sophie puts it: “I didn’t die from Covid, but I haven’t got better.” The inherent qualities of carers include putting others’ needs first. With the power imbalance and fear of taking on employers, occupational communities behave very differently from recreational ones.

I met Sophie through the Long Covid Support Group, through a concerted effort to encourage people of African descent to join meetings of the NHS Long Covid Taskforce and with health ministers to speak about their lived experiences. All of us who had fallen into the role of “representing the community” were white, and some of us worried that as (middle-class) white women we had the privilege to seek help and speak out, while other communities took the brunt of death and serious illness. As early as May 2020, the ONS was publishing careful statistics on the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on the UK’s black and Asian communities. It took months for government policy and messaging to catch up with the data; I'm not sure the community groups have caught up yet. The same happened in the early days of Aids. Invisible for too long, and often fearful of racist repercussions, African and Caribbean communities were also disproportionately affected by that virus – with poverty driving the uneven impact in different ways.

The epidemiology of infectious diseases matters. In 1986, the early, weekly reports of growing numbers of people with HIV alarmed and fascinated me – I tracked them closely, piecing together how the epidemic expanded among women in the UK . Epidemiology is a fascinating detective story – a science now practised from armchairs all over middle England, with people interrogating Chris Whitty’s nightly slideshows. In his 1987 book And the Band Played On , Randy Shilts (the San Francisco journalist who died of Aids-related complications in 1994, aged 42) describes in rigorous detail the daily endeavours of epidemiologists trying to piece together the trends at the start of the epidemic. In July 1981, four weeks after that first report, scientists at the CDC also found 20 men in New York with the same symptoms, and as he archly comments: “They weren’t all eating at the same restaurant.” Epidemiology is fascinating, and it is also political.

Larry Kramer’s angry essay “1,112 and Counting” changed the course of the Aids response in the US, documenting the relentless increase in deaths among gay men. His impassioned plea to gay men to understand the impact on their communities, entwined with neglect by the authorities created to protect them, led to the creation of activist group ACT UP (the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power – and it did). Opening with the line “If this article doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in real trouble”, Kramer’s essay is a masterpiece in using epidemiology to alarm and demand action (and I wish I had written my own version in May 2020). It’s a story expertly retold by David France (with the benefit of three more decades’ hindsight) who shows how the initial public health and political responses were slow, fearful and grounded in prejudice. In the Covid era, alarmed epidemiologists have taken to social media, creating “Independent Sage” and Twittering loudly with the same intent .

Many political responses to Covid-19 have been slow and inept, but for different reasons – several of which are currently being blown open through fierce political and media questioning. The early history of Covid already provides a clear case study in how politics and public health are entwined (in too many countries populism and economics have been prioritised over public health) just as Aids demonstrates how human rights and public health cannot be separated. In the UK, politicians with little or no understanding of science or health promotion offered contradictory and confusing messages on Covid, frequently undermining the role of the chief medical officer – a role that had been so important in the early years of the Aids crisis where Sir Donald Acheson quickly emerged as a voice of reliable scientific information and advice. From the outset, Aids was mediated through a hefty dose of homophobia and stigma against what we now (politely) call marginalised groups or key populations: those who were most vulnerable to HIV, including the vibrant communities of sex workers, drug users and gay men who already shared so much experience of being hated and criminalised. Communities had to take this on, as Australian activist Adam Carr noted as early as 1984: “We are the only people with the power to stop Aids, and this is our one great strength, our one ace. The doctors cannot stop it, the scientists cannot stop it, the government cannot stop it, except by helping us to stop it. Only gay men themselves can bring this situation under control, and we have the means to do it. If we publicly pledge ourselves to this objective, and if we achieve it, we will succeed not only in saving ourselves, but in saving the whole community, from the scourge of this dreadful disease. And the political consequences of such a victory will be as beneficial to us as the consequences of our failure to act would most certainly be calamitous.”

In 1998 I moved to Australia to lead the Australian Federation of Aids Organisations, hoping to learn from the best Aids response in the world. It’s no coincidence that many countries doing well in relation to Covid also did well on Aids. Australia and New Zealand know the importance of co-ordination, inclusive decision-making, valuing all communities, and governments communicating with affected populations in a straightforward, honest way. By contrast, the (many failings) in the Indian response include that “until April, the government’s Covid-19 taskforce had not met in months”.

And so we stayed at home, avoiding care. Many of us got very sick, few of us got any treatment. Thousands died needlessly

Serious public health challenges demand seriously good governance and effective political leadership. The shocking course of the epidemic in countries with populist leaders – think Bolsonaro, Johnson, Modi, Trump – contrasts dramatically with the success in countries with considered, thoughtful people at the helm. It is no coincidence that research on 35 countries found that those with female leaders “experienced much fewer Covid-19 deaths per capita and were more effective and rapid at flattening the epidemic’s curve, with lower peaks in daily deaths”. New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern is top of the crop, keeping Covid deaths well below 1/100,000 deaths; by contrast the UK’s rate is 190/100,000. Before we despair, there is real hope for transformation. Where governments get it wrong, there is still potential for course correction. The US demonstrated this clearly in the shift from Trump to Biden – something redolent of the massive changes in South Africa’s response to Aids when the murderous denialist policies of Mbeki and Tshabalala-Msimang gave way to the evidence-based effective scale-up of treatment and services by President Motlanthe and his health ministers Hogan and Motsoaledi.

Successful public health responses depend on good communication, exemplified by Ardern’s reassuring, but firm, introduction to her country’s lockdown measures – and her delightful national address giving the Easter Bunny and Tooth Fairy essential worker status. Of course, it was cute for a young mother to take children seriously, but her approach goes deeper, demonstrating a genuine appreciation of what it takes to support people to respond to unreal demands in the face of unprecedented challenges. Early Aids campaigns were successful because gay men spoke to each other in straightforward language, emphasising shared risks, and urging each other to take extraordinary measures to tackle unprecedented challenges. UK Covid campaigns have been striking by their absence of focus on the dynamics of transmission, and their hefty emphasis on rules and punishment. HIV messages and safer sex workshops focused on eroticising safer sex and encouraging people to do counter-intuitive things, giving detailed descriptions of why certain acts were and were not safe, and giving people the information and skills to make smart judgments in unexpected situations.

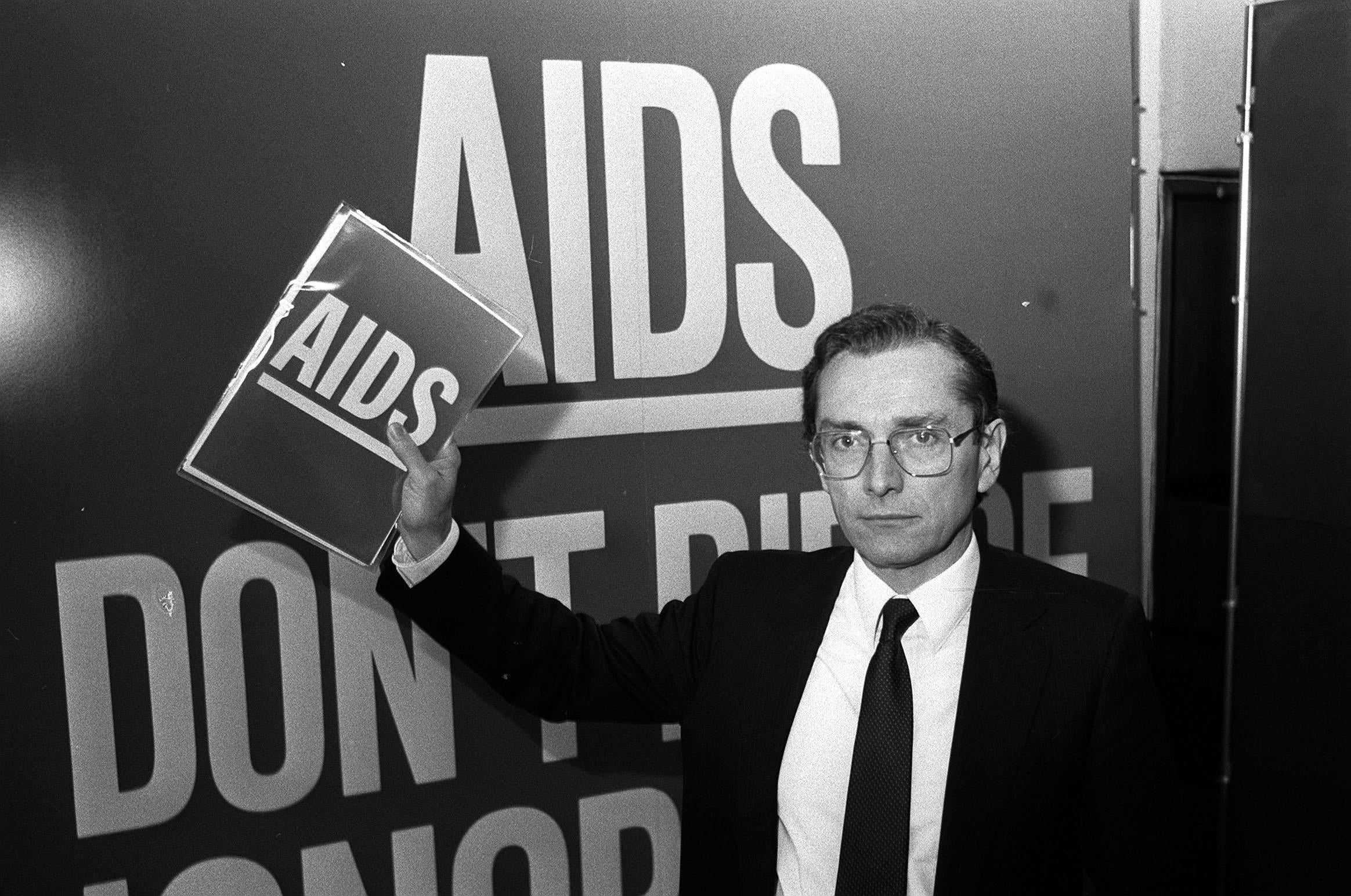

As with Aids, all households received a “vital update from the government about” coronavirus. March 2020 was just the second time letters had been sent to warn every household about a public health threat. By then at least 10,000 people had died. In 1986, when health minister Norman Fowler persuaded Thatcher to send out the “Don’t Die of Ignorance” leaflet, 275 people had been diagnosed with Aids. While far from perfect, at least it took people through the basics of how HIV was transmitted and how to avoid infection, with frank information about “risky sex” and “sharing needles”. By contrast the 2020 “information” is heavy on rules and slogans – with little attempt to explain how coronavirus is transmitted, and no advice on what to do if you got sick with it except stay at home. Accompanying posters screamed “If you go out, you can spread it, people will die.” But what to do if you did get it? The answer: “Stay Home.” Prevention is vital with a highly infectious disease, but – and this was often the same with Aids – messages failed to consider that their audience included people who were (becoming) sick or had recovered. And so we stayed at home, avoiding care. Many of us got very sick, few of us got any treatment. Thousands died needlessly.

It is remarkable that so much behaviour change happened so fast with both pandemics. As Covid lingers, the focus on criminalisation and lack of attention to how the virus is actually transmitted poses massive challenges. Lopsided messaging can only fail if individuals (such as students) are left to guess about risk minimisation measures, and risk fines even if they guess right. Criminalisation has never worked well in tackling Aids, and it is equally messy and ineffectual in stopping Covid. Terrifying people only works for a short time (if at all). As Aids epidemics matured and knowledge expanded, communities would adjust their health promotion messages. In the second decade, as HIV testing and treatment became easier to access, some gay communities adopted “serosorting”, meaning that (for example) men who had both tested HIV-negative would stop using condoms together – and then use them if they had sex with others who were (or might be) HIV-positive.

Not a perfect strategy, but a fine example of risk minimisation, rather than elimination – an essential strategy for living long-term with a pandemic. CDC director Walensky recently asked people to make their own (risk minimisation) assessment about whether they need to wear masks given the very high vaccine coverage: “If they are vaccinated and they are not wearing a mask, they are safe. If they are not vaccinated and they are not wearing a mask, they are not safe.” As the UK loosens restrictions, Boris Johnson’s messages start to include vague reference to “trusting people to make their own decisions”. Not only is this weirdly patrician, it seems doomed to failure given that thus far the government has not trusted people with clear information about how the virus is and is not transmitted. With complex demanding health messages, countries do best by bringing people with them creating a shared understanding of why different behaviour is needed. We learned that in Aids; we are lagging with Covid.

Happily, there are a couple of areas where the Covid response stands on the shoulders of the Aids response. The swift, collaborative development of effective vaccines builds on the excellent international collaborations set up by Aids researchers in the 1990s. And there is also real hope that access to Covid vaccines in poor countries will be achieved because activists are building on what we didn’t quite achieve in the past. Both pandemics are scarred by inequity and a hideous global divide with the poorest countries bearing terrible burdens of illness without the means to pay for the medical interventions that pull richer countries out of the depth of the mess. In Aids there was a massive treatment divide; for Covid it’s all about vaccines.

Over the past year activists for Covid vaccine equity have been pleading for big, powerful countries to waive the TRIPS (Trade-Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) agreement – a structural solution to the economic disparities that drive pandemics among the poorest people of our world. The energy has been fierce, my inbox creaking with sign-on letters and raging Op Eds from advocates on all continents explaining the complex nuances of how smart international negotiations could save millions of lives. Few of us expected the official US government tweet on 5 May, from trade representative ambassador Katherine Tai, who proclaimed: “These extraordinary times and circumstances call for extraordinary measures. The US supports the waiver of IP protections on Covid-19 vaccines to help end the pandemic and we’ll actively participate in @WTO negotiations to make that happen.”

It’s a perfect example of what smart – and very persistent – advocacy can achieve. Over two decades ago, smart Aids activists – such as indomitable campaigners Ellen t’Hoen and Jamie Love – figured out that one of the simplest ways to get drugs into (poor) bodies would be to stop companies boosting their profits (and with them the costs to poor countries) by charging for the IP (intellectual property) involved in developing them. Companies argue that without recouping their IP costs they will never develop new products; the counter-argument is that in the face of a global health emergency where medicines (for Aids) or vaccines (for Covid) are not affordable for most poor people, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) must force companies to waive the IP levy that big companies apply to the costs of new products; TRIPS is the bit of international law that governs who gets to profit. The US policy shift to advocate for TRIPS waivers is shaking big pharma to the core as it means that local companies could access the formulae needed to manufacture vaccines and drugs quickly and cheaply.

The explosion of mask designs and sales of hand cream to mitigate the impact of over-sanitising have made behaviour change desirable

Two decades ago local drug companies in South Africa started to make ARVs (antiretrovirals) to treat their (now 7.7) millions of people living with HIV. The pharmaceutical companies who had developed and licensed these ARVs took then President Mandela to court claiming that South Africa was breaching TRIPS legislation with this local manufacture (in essence that they had stolen the “recipe”). Mandela countered that Big Pharma was profiteering on the backs of the poor, and that the country with the largest Aids epidemic in the world should be allowed to make drugs for its people without paying Big Pharma for its IP. South Africa won.

Behind the snappy slogans “Pills not profits” lie extremely complex details of international law, and the power imbalance that rules international negotiations and the need for technology transfer as well as waiving legal restrictions. South Africa and India remain champions of rebalancing in favour of the countries that need – and can now manufacture – generic (aka “copycat”) products; but until 5 May the wealthier nations had continued to line up on the side of the multinational corporations and their IP protection. Instead of a structural solution they emphasised the more charitable style model of Covax – a global collaboration to accelerate the development, production, and equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines. Covax is hugely impressive but – like other global health bodies such as the Global Fund to Fight Aids, TB and Malaria – it will always be caught by the complex geopolitics of global health.

Hence the brilliance, and shockwaves with the US announcement. It took me back to 1998, when I had been elected as the first community co-chair of an International Aids Conference (IAC). In July, 10,000 scientists from all disciplines, policy makers and activists (and my one-year old twin sons) gathered in Geneva under the slogan “Bridging the Gap”. Covid began in a very connected world, whereas the Aids response began before we had email, mobile phones and social media to ping ideas and advocacy messages to other countries in seconds. The global response to Aids grew organically out of pre-existing connections, the recreational communities that shared information and resources (in the 1980s THT’s most popular information for gay men were posters from the San Francisco Aids Foundation repurposed with stickers with the local helpline number). As the epidemic expanded at pace, connections at all levels became powerful, with the massive international Aids conferences serving as a vital point of networking, scientific exchange, policy plotting and activism long before we had the ease and immediacy of our virtual world.

Haart – Highly Active Antiretroviral Treatments – had been revealed to the world at the 1996 IAC under the optimistic tagline “One World, One Hope”. It was painfully obvious that this breakthrough announcement only delivered hope to one part of the world. Two years later we had great hopes that we could use the conference to make change, but The Lancet questioned whether the event had “the muscle to persuade the drug industry that its prices are too high”; Richard Horton concluded: “We think not.” As usual he was, sadly, right. Despite intense efforts we could not get a single representative of the pharmaceutical industry to speak publicly at the conference, despite many opportunities where we debated the issue repeatedly. They chose instead to meet behind doors with UN leaders Kofi Annan and Peter Piot. I recall chairing a vibrant and detailed panel where Jamie Love and others presented an impassioned call to arms explaining how IP legislation, and TRIPS waivers in particular, would deliver Haart to poor countries far more rapidly than any charity scheme. The cries for it never ceased, but I often feared it was an activist pipedream. Three months ago, I was contacted by Gareth Thomas MP. I’d worked for him at DFID back in 2005 when we scaled up the UK response on Aids: could I remind him of those complicated arguments about TRIPS? On 20 May, the Labour shadow cabinet wrote to international trade secretary Liz Truss proposing a 10-point plan to maximise production and equitable distribution of Covid-19 vaccines around the world. The same NGOs , 15 years ago, had buzzed in my former minister’s ear about access to HIV treatments for poor countries were back demanding action on the new pandemic.

The Aids-Covid connections can be found at many levels of culture, society and policy. These range across the eerie similarities between the anti-condom proponents and the anti-maskers , and related opportunities to promote simple messages (Wear them inside!) - and by contrast the lagging cultural responses to Covid. Learning to live safely with both of the viruses is very empowering. In the same way that we eroticised safer sex and condom manufacturers developed multiple colours and flavours, the explosion of mask designs and sales of hand cream to mitigate the impact of over-sanitising have made behaviour change desirable. Contrast this with all the inaccurate and unclear information that can make people go a little crazy - whether the panic about kissing (how many hours did I spend in the 90s describing the concentration of HIV in saliva?) or the extreme measures washing food in bleach, then leaving it to linger for three days outside the backdoor. The massive need to integrate behavioural and psychosocial research into a multi-disciplinary response was something we got right in Aids at the beginning, but it’s not happening yet in Covid. And there is no meaningful engagement of people living with Covid in any response – global or local – unlike Aids where it is a non-negotiable requirement.

We need to find smart ways to live with the nagging complexities of an unknown disease course ahead

The need to get treatment activism off the ground and balance focus on prevention with the urgency of early interventions and better treatments is also trailing far behind. Of course vaccine development has been remarkable, and unexpectedly swift – contrast with HIV where 40 years on vaccines continue to elude us. Yet we are astonishingly slow with the Covid treatment progress. I remain shocked that one year on there is none of the loud clamour for treatments among the now millions of us living with Long Covid. In the Eighties and Nineties people with Aids demanded access to experimental drugs to have a chance of survival; in 2020 one high profile president was pumped full of experimental anti-Covid drugs. He seemed to recover quite quickly. What about the rest of us? Could I have been spared 10 miserable months of health challenges and time off work if experimental drugs had been available? What about all the GPs, midwives, nurses, anaesthetists etc, trained at huge expense, desperate to work, but stranded by their occupationally acquired infections with nothing but online physiotherapy on offer. In the global collaborations all eyes have (understandably) been on the vaccine with next to no funding or energy devoted to treatments – for the millions of us with lingering illnesses, and the millions more who will become sick. That has to change.

Covid responses must also learn from the centrality of human rights in Aids responses. Conversations about vaccine passports, requiring certain cadres of employees to be vaccinated, approaches to criminalisation would all do well to learn from the deep discussions among Aids experts about how to get this right, how to balance “rights and responsibilities”, how to motivate for effective behaviour change rather than punish breaches. The same goes for efforts to tackle stigma, and the very different rationale for the discrimination many of us have experienced. We must learn to get the language right – the WHO demands that diseases are never named after places or people .

We swiftly stopped calling Aids “Grid” (Gay Related Immune Deficiency) and we must learn to talk about B 1.617.2 – unless we want to see Asian hate crimes rise among Indian communities in the same way that they affected Chinese communities when leaders foolishly spoke about “the Wuhan virus” and worse. I was struck in recent days to read the death notice for an amazing colleague who died suddenly with Covid; their family chose to reference our friend’s underlying health condition, not the Covid. Many of us gathered (having taken lateral flows, and keeping our distance) to farewell our colleague, adapting a ceremony that we had developed over the past decade to farewell other friends who had lost their lives to Aids. As numbers keep on expanding at pace, we need to learn from the past and find smart ways to handle the multiple loss and bereavement that communities and countries are experiencing as we face Covid and its uneven impact. Our Aids communities have got used to this. Before Haart we had the ever expanding Quilt to memorialise the constant loss. Over the years we have adopted rhythms and rituals, gathering friends and creating ceremonies. Perhaps imperfect in the Aids response, but the communities most affected are the first generation since world wars to have faced communal loss on this scale. We have tales to tell, ideas to share.

On a very personal level, the need for smarter more focused treatment activism feels especially important. I got heavily involved in Aids treatment activism in the late 1980s and early ’90s, advocating as an ally for my friends – especially women – living with HIV. At the time, I remember many people asking “how will HIV affect people in 20 years’ time?” Something that was de facto unknowable then, just as the natural history of Covid, and its lingering sequel, is now. Who knows what 10 years with Long Covid looks like? Currently I am rejoicing at a massive “vaccine bounce” in my own symptoms. In the absence of real time action research, and clear, focused demands from activists with similar experiences, we need to find smart ways to live with the nagging complexities of an unknown disease course ahead. With a new disease you don’t know, until you know. But with this pandemic, we have a lot to learn from what happened four decades ago. It is still not too late to learn from that history, and avoid repeating its most wretched aspects.

Robin Gorna is the head of diversity and inclusion at Brighton College, and is one of the Focal Points for Human Rights and Gender Experts on the Technical Review Panel for the Global Fund to Fight Aids, TB and Malaria. She served as a member of the NHS Long Covid Taskforce from September 2020.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments