Largest ever 3D map of the universe fills in mysterious, 11-billion-year 'gap' in history

Study reveals 'cracks' in our understanding of the cosmos, researchers say – including the fact we don't know for sure how fast the universe is expanding

Scientists have filled in a mysterious 11-billion-year gap in our history of the universe – and have come across another puzzle.

New analysis of the biggest three-dimensional map of the universe ever made has helped fill in the strange missing period in the middle of the existence of our cosmos. Scientists have long had a good view of how the universe looked at its beginning, and in the last few billions of years – but they can now fill in the gap in the middle and tell a full story of the development of our cosmos.

But it has helped to lead to further puzzling questions about our picture of the universe, including the central question of exactly how fast it is expanding.

“We know both the ancient history of the universe and its recent expansion history fairly well, but there’s a troublesome gap in the middle 11 billion years,” said cosmologist Kyle Dawson from the University of Utah, who led the team announcing the results, in a statement. “For five years, we have worked to fill in that gap, and we are using that information to provide some of the most substantial advances in cosmology in the last decade.”

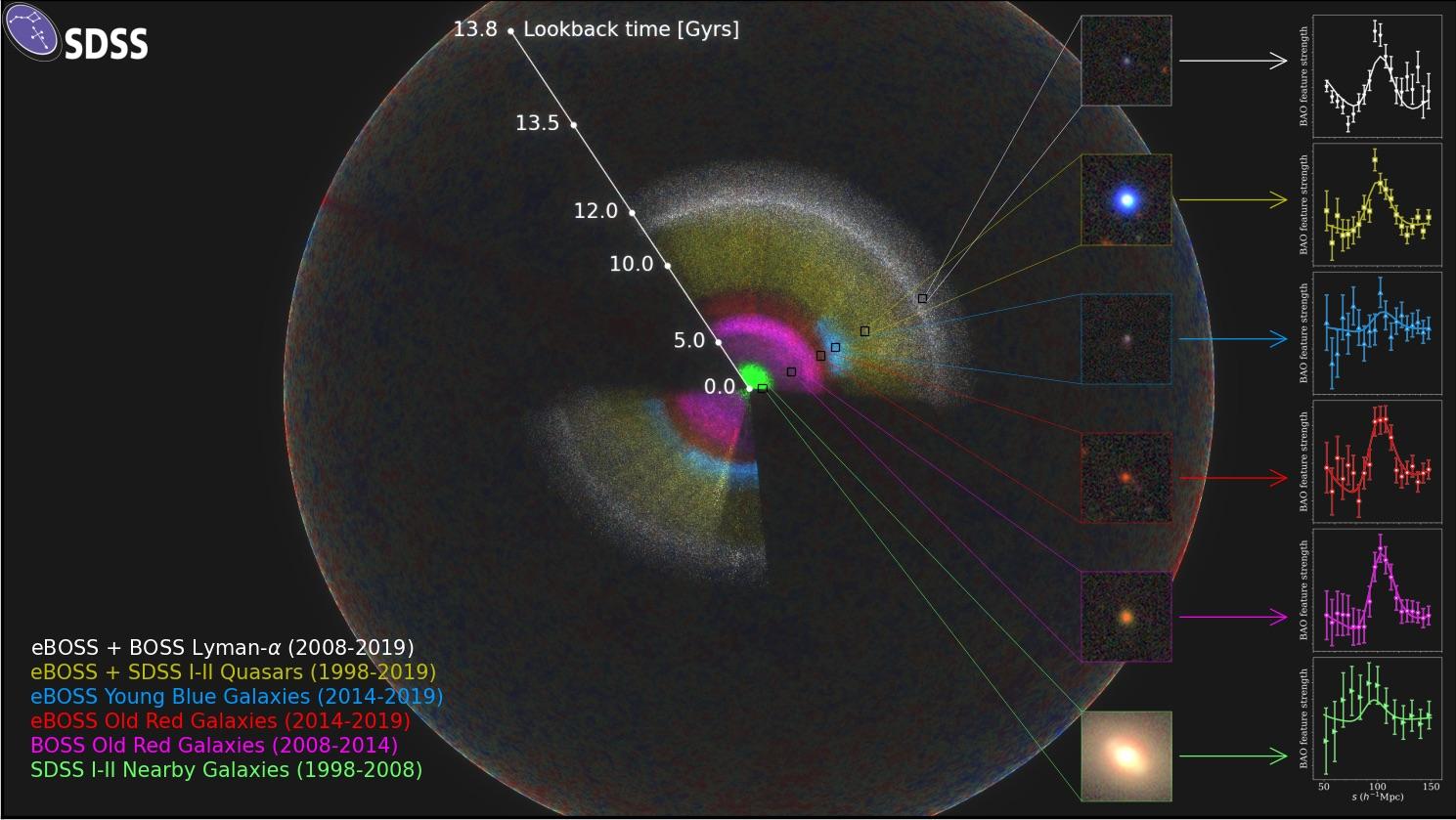

The new work took data from the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey, which has looked to create a detailed map of the sky. It particularly relied on detailed measurements of more than two million galaxies and quasars, which together give us a view of those 11 billion years of time that has appeared be missing.

“Taken together, detailed analyses of the eBOSS map and the earlier SDSS experiments have now provided the most accurate expansion history measurements over the widest-ever range of cosmic time,” says Will Percival of the University of Waterloo, eBOSS’s Survey Scientist. “These studies allow us to connect all these measurements into a complete story of the expansion of the universe.”

Images released by the team – as part of new research that allowed 20 different papers detailing the new studies – show that map, which depicts the filaments and voids that make up the universe, starting just 300,000 years after it came into existence.

That more complete story of the development of the universe showed that the expansion of the universe seemed to accelerate around six billion years ago. Ever since, it has got faster and faster.

That strange expansion seems to be the result of dark energy, which both answers questions and poses new ones: that understanding of the universe is in keeping with Einstein's general theory of relativity, but poses difficulties for our understanding of particles physics.

But the new study also indicates that we might not even be right about the speed of that expansion. The new study's measurement of that rate – known as the Hubble Constant – is about 10 per cent lower than it is in studies that use nearby galaxies.

There is little chance that the difference is the result of an accident, the researchers say, especially since the data in the new research can be used in various ways to calculate the same number.

Instead, there is a problem with our measurements of the Hubble Constant that cannot be easily explained away, the researchers said.

“Only with maps like ours can you actually say for sure that there is a mismatch in the Hubble Constant,” said Eva-Maria Mueller of the University of Oxford, who led the analysis to interpret the results, in a statement. “These newest maps from eBOSS show it more clearly than ever before.”

The changes in the rate of expansion could be the result of an otherwise unknown form of matter or energy that we can see the effects of, researchers say, but further work must be done to understand the puzzle.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks