The home DNA testing company 23andMe has gone bankrupt, so how safe is your data now?

23andMe was once the darling of postbox DNA testing, but after a colossal data breach and months of business turmoil, the company has finally gone into administration. So, what’s next for your most personal data, asks Zoe Beaty

In the middle of 2008, a room full of celebrities and socialites gathered in a room for cocktails, clutching plastic tubes filled with saliva. It was New York Fashion Week, and the attendees were some of the first to take part in a very new sort of socialising: a “spit party”. Connotations aside, it was a clever start for a relatively unknown genetics testing company. 23andMe made headlines around the world, kicking off a journey to “personalise genetic healthcare” that would culminate in a business worth $6bn (£4.7bn) at its peak in 2021, and a global conversation around one important question: who really owns your data?

Now, 16 years on, 23andMe is back in the headlines – and this time, it’s not so rosy.

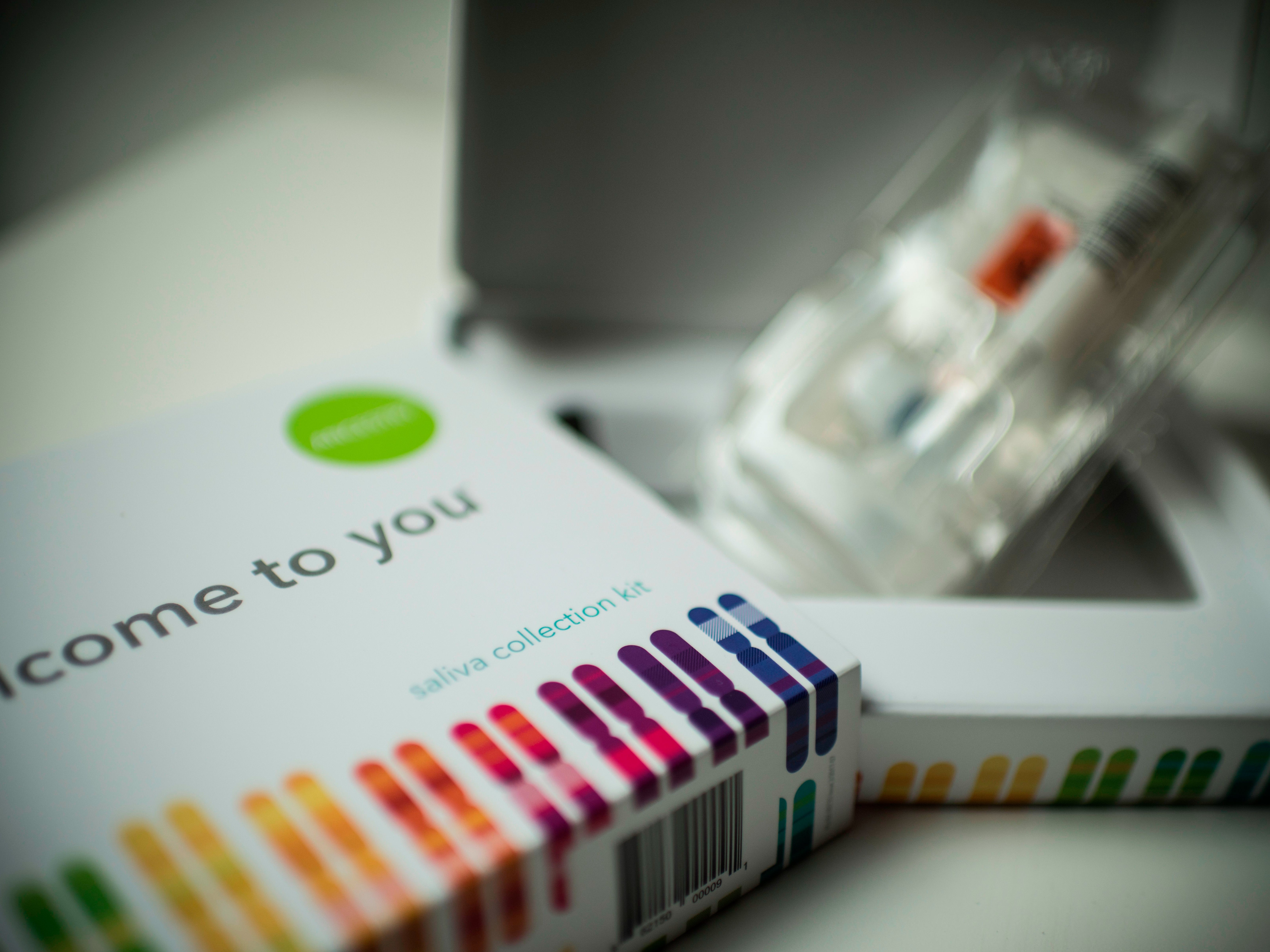

The US genetic testing company 23andMe has filed for bankruptcy protection in America to help sell itself, confirming its chief executive, Anne Wojcicki, has stepped down. The company, which provides saliva-based test kits to customers to help them track their ancestry, added that it was operating as usual throughout the sale process. “There are no changes to the way the company stores, manages, or protects customer data,” it said

However, it is still reeling from the huge data breach, which began in April 2023 and lasted for five months, affecting almost half of its 14.1 million customers; the resulting US lawsuit cost the company $30m to settle in September last year. The same month, its board unanimously rejected the “strategic direction” of its founder and CEO, Anne Wojcicki and all seven resigned leaving the the genetics testing company to fall into dissary, with its values plummeting.

“I believe in the company. I believe in the long-term mission,” Wojcicki said in an interview with US talk show CBS Mornings last year. “But I believe it’s essential for us to restructure.” She oversaw the redundancy of more than 40 per cent of 23andMe’s workforce and then despite her insisting the company will be “growing and thriving” in its mission to “transform health care” in the next five years it failed to recover its fortunes.

In a post on X, Wojcicki said she was “disappointed” by the bankruptcy filing and that her bid to take the company private was rejected which is why she resigned: “So I can be in the best position to pursue the company as an independent bidder”. Adding, “If I am fortunate enough to secure the company’s assets through the restructuring process, I remain committed to our long-term vision of being a global leader in genetics.”

Wojcicki’s belief in the company is in her genes. Her sister, Susan Wojcicki, former long-term CEO of YouTube, helped enable the creation of Google in 1998 when she rented out a garage to its founders – one of whom, Sergey Brin, would become Anne’s husband as well as one of 23andMe’s first backers. From the beginning, the consumer-friendly genetic test also attracted early, token financial backing from the likes of Wendi Murdoch and Harvey Weinstein, but really, it was her clever marketing, and the human trait it targeted – curiosity, and especially curiosity about ourselves – that would make the company soar.

The test was initially sold as a way to social network, according to the press at the time. Your DNA might connect you with communities who have psoriasis, or a voracious sweet tooth, or who are also susceptible to bowel cancer. Once posted off, the 89 genetic markers might also reveal intriguing – or life-changing – information about your family. Perhaps you’re not “one-quarter Irish”, as your Grandma insisted; perhaps you were adopted all along. The novelty of collecting your own stories was, and still is to many, beguiling. It’s also a warning story that defines a generation that blindly walked into the internet. Now, the consequences of those actions – of throwing our most personal, sensitive information into the unknown – are beginning to appear.

Before its more recent challenges, 23andMe had been continually looking to expand its remit – while the curiosity boom worked for a while, selling one-time kits eventually became a financial cul-de-sac. Subscription models wouldn’t cut it, either: Wojcicki saw the company’s future in drug discovery. “23andMe’s Pharma Deals Have Been the Plan All Along”, one Wired headline read in 2018 – it had just signed an exclusive contract with GlaxoSmithKline, who invested $300m.

The “plan” was to use genetics to change and influence healthcare scale. It saw some success: one drug the company developed, 23ME-00610 – a monoclonal antibody that, very simply put, works by reactivating the immune system’s response to tumours – has shown early signs of success.

23andMe maintained that “transparency is a core tenet of the company”, the report said – proper guidelines around reusing the data collected by those who purchased at-home tests were followed. But tension grew – the company had always been positioned as a consumer-first, healthcare aid, yet its practices became more meaningfully “big tech”. Customers were informed of how their data might be used elsewhere in medical research, and they retained the power to opt out at any time, but some began to feel betrayed and, perhaps for the first time, to question where their data was going. The thing is, who reads the small print?

Those implicated in 23andMe’s significant data breach might give it a go now. According to Reuters, “the hacker accessed 5.5 million DNA Relatives profiles, which let customers share information with each other, and accessed information for another 1.4 million customers who used a feature called Family Tree”.

The settlement case that ensued also resolved “accusations that 23andMe did not tell customers with Chinese and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry that the hacker appeared to have specifically targeted them and posted their information for sale on the dark web”.

The company informed their customers of the breach in a blog post. In June, the UK’s information commissioner John Edwards and Canada’s privacy commissioner Philippe Dufresne agreed to begin a joint investigation into the 23andMe breach, in order to examine the scope of information exposed and whether the company had adequate safeguards and had made appropriate notification to regulators when the breach occurred.

But the size of 23andMe meant it was always going to be at risk when it comes to data, says Jake Moore, global cybersecurity adviser at ESET. “When you've got such a huge user base, you paint a target on your back,” he explains. “Because all you’ve got to do as a criminal hacker is to find that one vulnerability, which, let’s face it, is clearly going to be somewhere. If they can exploit that, then they have access to huge amounts of data, with the possible chance of extorting people dramatically. Even just the threat of that is hefty enough.”

Moore says that, during the early 2000s Millennial tech boom, data protection and regulation were less of a priority than they are now. For most companies back then, “The focus was making money,” he says. “It was this new age of using social media, using celebrities – this idea of big or go home. Most never even expected to be [data] breached.”

If a hacker is able to look into people’s medical histories, they can start to put a profile on them, Moore explains. If a name, an address or other sensitive information is also attached, it adds to the risk of identity theft, too. “It just opens up this huge can of worms. And what we’ve learned from previous data breaches is that once your data is out there – once the can is opened – it never gets put back. It’s always going to be there, whether it’s on the dark web, the open web, or just circulating on lists that are sold on by even legitimate companies. You never get to put it back.”

Now, the future of 23andMe, with Wojcicki waiting in the wings to buy the company, remains to be seen . Certainly, the genetics-at-home bubble appears to have been dramatically burst. For the rest of us, the message is clear: long gone are the days when we innocently uploaded hundreds of photos to Facebook weekly, or thoughtlessly popped our most precious data, our DNA, in the postbox. Who owns our data? Who knows. But it’s time to read the small print for whatever comes next.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks