From traumatic brain injury to an Alzheimer’s treatment

In association with University of West England: There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s disease and even diagnosing the condition can take years of tests. For a disease that affects more than 520,000 people in the UK, and several million worldwide, this is not good news.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s disease and even diagnosing the condition can take years of tests. For a disease that affects more than 520,000 people in the UK, and several million worldwide, this is not good news.

But new research could lead to a faster way to diagnose Alzheimer’s as well as to a treatment that would involve simply taking a supplement to delay the condition’s development. Many of the early symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as short-term memory loss and mood swings, are signs of normal ageing or other conditions. Only one-third of patients with the symptoms will go on to develop Alzheimer’s – and it is difficult at the moment for clinicians to tell whether they are witnessing the early signs of Alzheimer’s or something different.

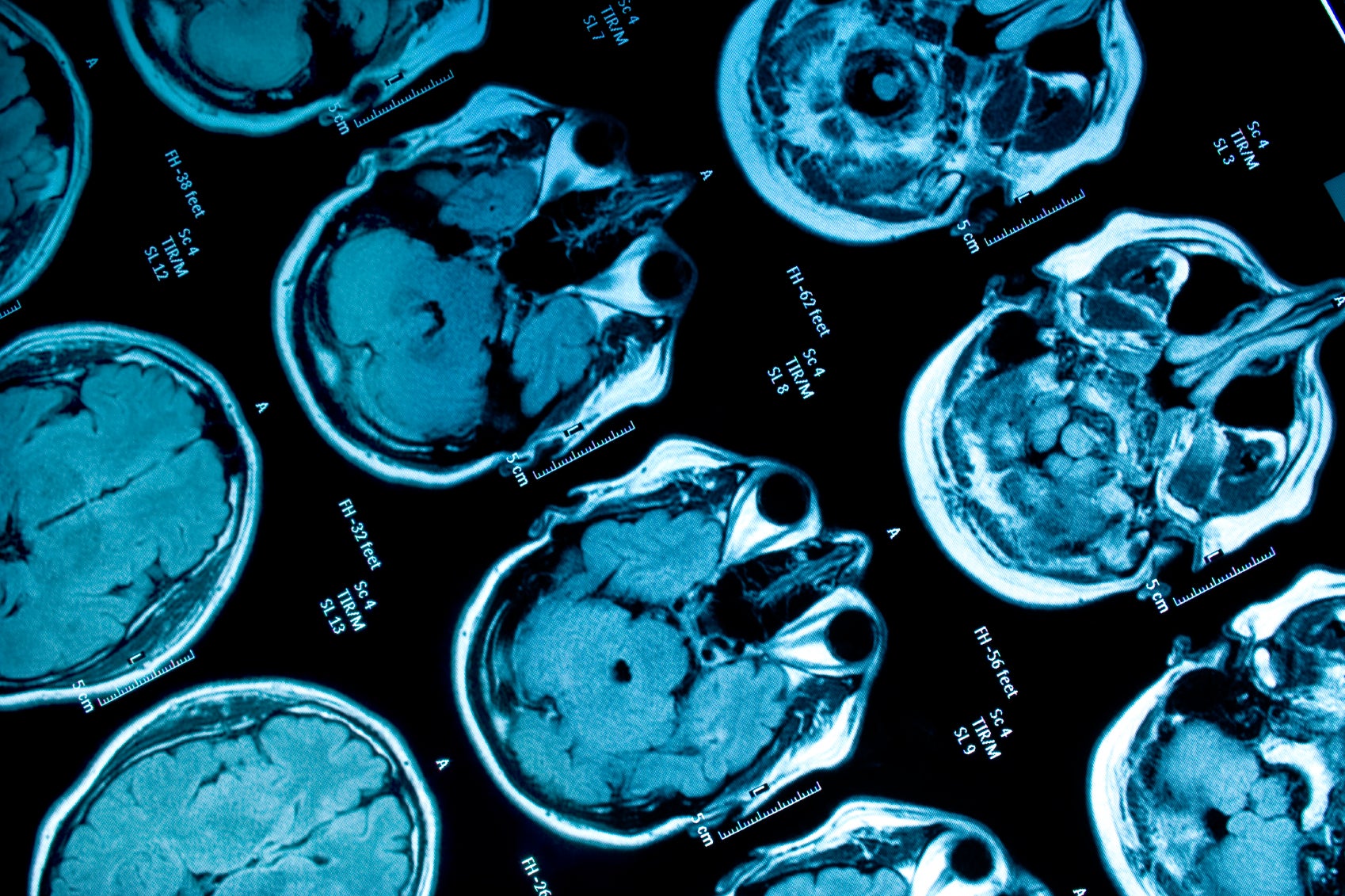

Patients suspected of having Alzheimer’s first take a questionnaire to assess their mental abilities; they may then have a brain scan. It can take months, or even years in some cases, for an Alzheimer’s diagnosis to be confirmed. However, Professor Myra Conway of the University of the West of England’s Centre for Research in Biosciences, is working towards a blood test that would enable early diagnosis.

Professor Conway has found early evidence that the levels of three “redox proteins” increase in the cerebrospinal fluid of those with Alzheimer’s. She is now looking to see whether the levels of these proteins also increase in the blood. If they do, checking levels of these proteins would provide doctors with a new diagnostic tool. The research is being supported by £50,000 from the Freemasons’ Grand Charity, after an application for funds supported by the UK charity BRACE.

A separate line of research is inspired by patients who have suffered traumatic brain injuries, for example in a road traffic accident. “It’s been found that levels of certain components of the blood drop in those who have suffered a traumatic brain injury, and that glutamate levels increase,” says Professor Conway. “Glutamate is toxic to the nerve cells in the brain, resulting in neuronal loss.” Giving supplements containing the depleted blood components to patients who have suffered a traumatic brain injury has been shown to restore some cognitive abilities. Some patients have even come out of a vegetative state.

This raises some intriguing questions. “Is there an indication that the profile of these blood components also changes as patients with mild cognitive impairment get older?” says Professor Conway. “Is there a way that if levels of these components start to drop, we can supplement what’s naturally there?

“Supplementing these components would not cure Alzheimer’s, but it might delay its progression if the treatment starts early enough; a patient’s cognitive reserve may be preserved. It could improve their quality of life.”

Early research is looking at the biochemical processes involved in the regulation of glutamate levels in cell models in the lab. Professor Conway and her team also plan to measure levels of blood components in Alzheimer’s patients to see whether, as in the case of sudden brain injuries, they are relatively low. It’s already known that the glutamate levels cause toxicity and contribute to the destruction of neuronal cells.

If these supplements are found to slow the progression of cognitive decline, the long-term implications are huge. “The impact of this treatment on the lives of Alzheimer’s patients and their families would be phenomenal,” says Professor Conway. “To be able to maintain their cognitive reserve would give them their lives back.

This content was written and controlled by the University of the West of England

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments