100 years of Roald Dahl

Children’s literature expert Dr Ann Alston reflects on the delights and dilemmas of Roald Dahl to celebrate the author’s centenary

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It all began, as they say in children’s stories, when standing in the bookshop, eye-to-eye with a stack of bright untouched hardback copies of Roald Dahl’s new book, Matilda. My mother said: “You’ll have to wait until the paperback comes out.” But in a swoop of bad parenting – and to the fury of my mother - my father picked up the book and bought it. Little did he know the impact of that moment, and 28 years later, here I am preparing for the celebrations of Roald Dahl’s Centenary.

As a lecturer in children’s literature, I’m more than used to friends, neighbours, random people on the streets and, occasionally, even students, asking “what’s the point?” After all, it’s just children’s literature.

But that is the point - I expect most of you read Roald Dahl as children. Not everyone will have read the whole of Milton’s Paradise Lost or Dickens’ Great Expectations (unless you graduate from UWE Bristol’s English degree), but everyone will have read some children’s literature, from the Prime Minister to the Security Guard, and that is one of the reasons it matters so much.

It gives us our first experiences of stories; it tells us how the world around us works, and often it gives a picture of how we as adults would like the world to be rather than how it actually is.

I’m sure we all remember that particular type of children’s literature with the didactic element, where the little monster who has been rude throughout, discovers he has no friends anymore, and ends the book a changed diplodocus.

Dahl doesn’t do this. In Dahl, the child tends to come out on top: Matilda defeats the Trunchbull and goes to live with Miss Honey; James, captain of his peach, squashes the terrifying aunts Sponge and Spiker as he embarks on his journey; Sophie escapes the orphanage and helps the BFG to defeat the bloodthirsty bullying giants; Little Red Riding Hood memorably, whips a pistol from her knickers and shoots down the wolf.

Dahl once said: “If you want to remember what it’s like to live in a child’s world, you’ve got to get down on your hands and knees and live like that for a week. You find you have to look up at all these bloody giants around you who are always telling you what to do and what not to do.”

It seems, then, that he’s on the side of the child, it seems simple and this is one of the reasons he appeals, that his books have been translated into more than 50 languages and that he continues to figure in several top-10 children’s reads.

But what I find fascinating about Dahl is his complexity: the dilemma of Dahl is that he appears on the side of the child but, actually, he also demands they conform to his views. When Dahl’s narrator sneaks up to us and says: “I’ll tell you a secret about grown ups,” then we are completely in his power.

In Matilda he gives us a list of books to read which will make us “better people”. And, although this list is essentially made up of the classics of English Literature, Dahl’s books were never appreciated by academics and educationalists during his life, but were rather branded misogynistic or racist.

Even though Dahl hated educational establishments (in Matilda, Mr Wormwood tellingly exclaims: “Who wants to go to University for heaven’s sake? All they learn there is bad habits!”), he nevertheless demanded that high standards be maintained; he despised the Establishment but also seemed to long to be a part of it. And though I argue his childhood - just over the bridge from Bristol in Wales - was formative, there is little mention of it in his books, for he was at once Norwegian, Welsh, English, and American.

Dahl, as my own PhD supervisor Professor Peter Hunt once told me, was a shrewd cookie. This shrewd cookie has become a national treasure. As schools across the country celebrate his work next week, the carnivals will begin - and so they should - for we will continue to delight in Dahl’s dilemmas and complexities for generations to come.

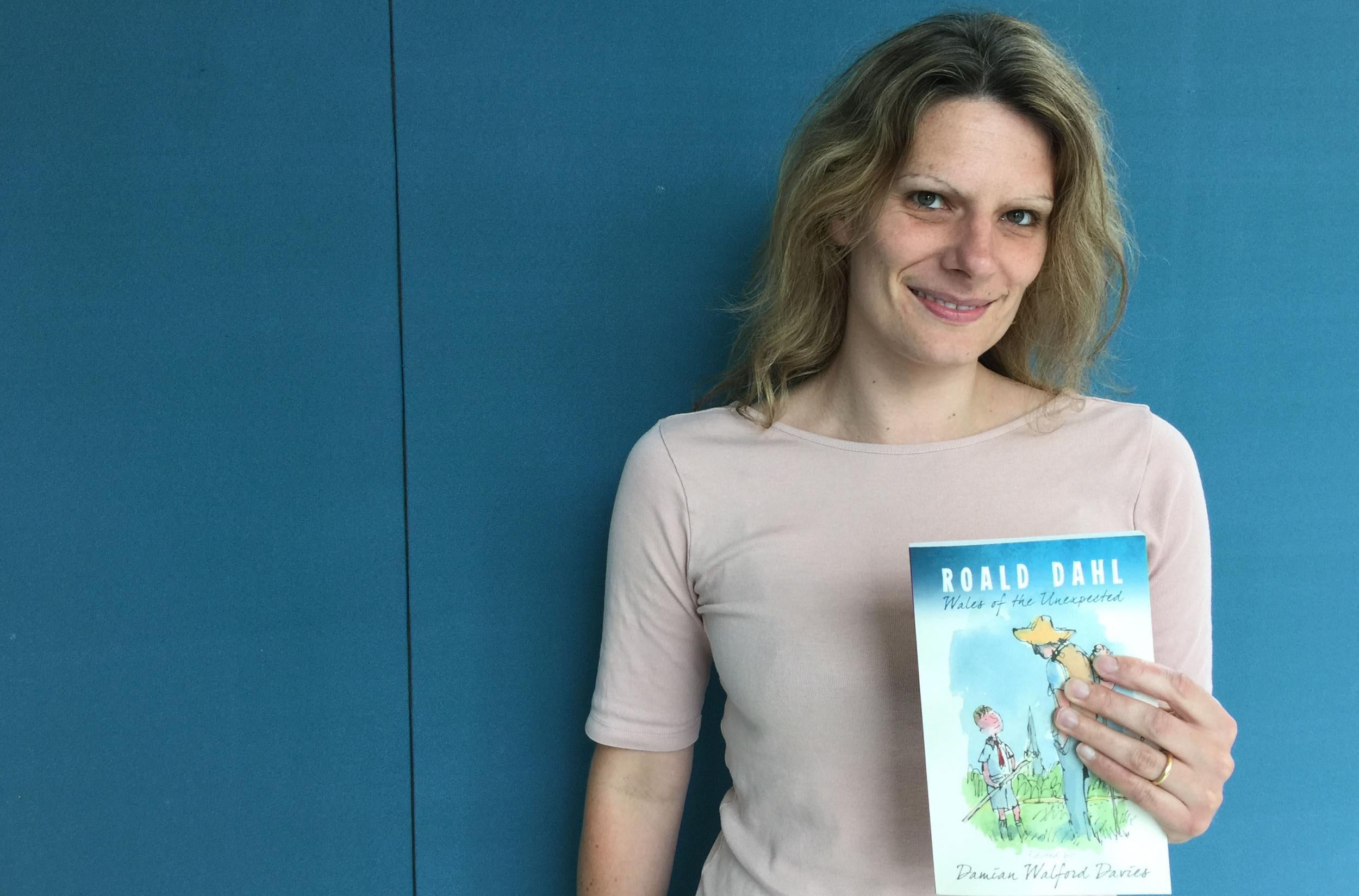

Dr Ann Alston is a senior lecturer in English Literature at UWE Bristol where she specialises in children’s literature. Having published her book on Family in English Children’s Literature (Routledge, 2008), Dr Alston went on to expand her research into Roald Dahl’s children’s literature, co-editing with colleague Catherine Butler, and contributing an essay for the first critical collection of work on Roald Dahl - Roald Dahl: A new casebook (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). She has recently written as essay for a new collection of essays centred on Roald Dahl’s connections with his birthplace; Roald Dahl: Wales of the Unexpected (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2016).

*This content was written and controlled by the University of the West of England

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments