British education in crisis? Literacy and numeracy skills of young people in UK among lowest in developed world

Pupils worse at maths and English than grandparents with England 22nd for literacy and 21st for numeracy out of 24 countries

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Young people in the UK lag behind most of the Western world in their mastering of the basic skills of literacy, numeracy and IT, according to an influential study published today.

The report, by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, shows there has been no improvement in performance in the basic between today's 16 to 24-year-olds and their grandparents' age (55 to 65-year-olds).

Indeed, they are the only ones in the western world to fare worse than their older peers in the tests in the basics.

The findings may have major implications for the UK's ability to compete in the global economy in future years - threatening it with a major skills shortage, according to the OECD's deputy director of education and skills and the coordinator of the project, Dr Andreas Schleicher.

They also put a question mark over the validity of improving exam results in the UK and lend credence to claims made by Education Secretary Michael Gove - among others - of grade inflation, particularly at GCSE level, over the past decades.

"Today's young people (in the UK) are not any better skilled than people in the older generation," Dr Schleicher said. "Young people in the UK are considerably behind their peers in other countries.

"One of the reasons why the older generation does reasonably well is that they keep learning and improving their skills - but young people in the UK lag quite a bit behind in basic skills."

The report concludes: "In England, adults aged 55 to 65 perform better than 16 to 24-year-olds in both literacy and numeracy. "In fact, England is the only country where the oldest age group has higher proficiency in both literacy and numeracy than the youngest age group after other factors, such as gender, socio-economic backgrounds and type occupations, are taken into account.

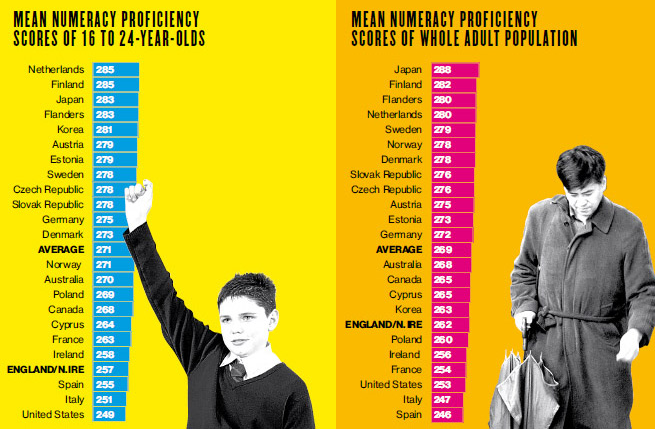

The figures show that, in England and Northern Ireland (the two parts of the UK to take part in the tests), 16 to 24-year-old scored 266 on average in the literacy test - putting them third from bottom in the 24 nation league table with only Spain and Italy behind them. Japan topped the table with a score of 299.

In numeracy, the UK 16 to 24-year-olds scored 257 - putting them fourth from the bottom with Spain, Italy and the United States behind them. The US was last.

The England/Northern Ireland figures for young people compared with an average score of 272 and 262 respectively when all 16 to 65-year-olds' scores were counted up.

In addition, a breakdown shows the UK now provides just four per cent of the highest flyers of all the countries taking the test compared with eight per cent of all 55 to 65-year-olds.

The figures were immediately seized upon by Conservatives as evidence that young people educated under the last Labour government were "amongst the least literate and numerate in the developed world".

Skills Minister Matthew Hancock said: "This shocking report show England has some of the least literate and numerate young adults in the developed world. These are Labour's children, educated under a Labour government and force fed a diet of dumbing down and low expectations.

"We are fixing the problem with a more rigorous curriculum, better teaching, higher standards and tougher discipline."

Mike Harris, head of skills at the Institute of Directors, added: ""The OECD's report makes truly depressing reading. It underlines the credibility gap between the picture painted by decades of rises in exam pass rates and employers' real-world experience of interviewing and employing people,

"Too frequently, impressive examination results seem to act as a false barometer of actual attainment and competence."

The report concluded: "The implication for England and Northern Ireland is that the stock of skills available to them is bound to decline over the next decades ubless significant action is taken to improve the skills proficiency amongst young people."

The tests - in numeracy, literacy and IT skills - were carried out on 5,000 adults in each participating country and aimed to show how much use adults made of the skills they had learnt at school in the workplace.

They showed -as well - a starker link between people's performance and their backgrounds in England and Northern Ireland. Adults who had at least one parent involved in a university-level education scored 26.7 points higher in literacy than those with parents who did not pursue such qualifications. This compared to an international average of 18 points difference between the two groups. In numeracy, the figures were even more stark - a 31.1 point difference in the UK compared with 19.5 internationally.

"It is deeply worrying that our young people are no better skilled than their parents' generation," said Sally Hunt, general secretary of the University and College Union. "If we are to stay competitive in the global market we need a strong supply of highly-skilled workers.

"The poor performance of the UK in terms of skills is linked to lower investment in post-16 education including in colleges and universities, as well as a culture which makes lifelong learning difficult and expensive for those who need it most."

The crumb of comfort, though, that the UK can take from the league tables is that it is more effective in using the skills of its highly performing adults than most other countries.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments