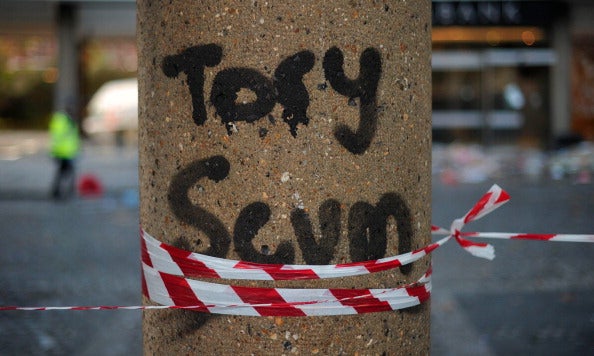

How the Conservative Party systematically alienated itself from a generation of young people and students

'Jeremy Corbyn’s successful election campaign was symptomatic of a generational dissatisfaction with a government who no longer seem interested in them'

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

This is an obituary. The subject may still be living, but its demise has been there for all to see for some time now.

Since the election of the coalition government in 2010, the Conservative Party has systematically alienated itself from a generation of young people. The last six years have seen successive increases in university tuition fees and an increase in the socio-economic marginalisation of young people.

2010 saw a fee rise from £3,290 to £9,000 in the wake of the Browne report amid cuts to the funding of youth services and a series of deeply unpopular educational reforms undertaken by Michael Gove.

These measures have proved deeply unpopular. Gove’s education reforms were met with a succession of rolling teacher strikes while upwards of 30,000 students and young people protested in London in opposition at the Government’s plans in 2010. Successive demonstrations over fee changes have seen violent confrontations between both police and students.

Then, after July’s emergency Budget which saw the scrapping of maintenance grants , last month’s green paper on higher education saw a commitment to a possible rise in tuition fees with inflation, as well as a shift towards a more marketised platform of higher education.

Crucially though, under present proposals, graduates will now leave university with debts in excess of £50,000 while those from the lowest economic demographic will graduate with debts of a higher level.

For a government that fought and won an election on a message of providing ‘a brighter’ and ‘more secure future’, young people seem ostracised by a government that seems increasingly out-of-touch with their practical concerns.

However, this narrative takes place amid a systematic economic recovery with the news that graduate employment levels have returned to their pre-recession level; according to a November 2014 survey undertaken by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), 82,000 people who graduated in 2011 - around 88 per cent - had secured work. Another recent graduate employment survey found that of 267,735 people who graduated last summer, 76.6 per cent had secured work.

Josh Boyle, a member of King’s College London Conservative Society, described how he’s not convinced that students, and young people in general, are dissatisfied with the Tories.

He said: “While it’s true the National Union of Students takes a consistent anti-Tory line on pretty much anything from tuition fees to the Syria crisis and all points in between, they are categorically not representative of all students.

“I think most students will be fairly satisfied with the Conservatives’ rule. By handling the economy in a safe way, the Conservatives provide vital economic and physical security for everyone - something I just can’t say of Labour at the moment.”

Despite this, the Conservatives appear to have positioned themselves directly against the salient interests of young people.

Callum Cant, a member of the National Campaign Against Fees and Cuts, however, insists students and young people have been “systematically attacked” by the Conservatives since 2010.

He said: “It makes complete sense there is a developing antagonism towards a party that has tripled tuition fees, marketised education, presided over a real wage crash, and a housing price spike.

“Clearly, when policy is being developed, students and young people are treated as a soft target and this will continue - until we get organised and fight back.”

The last six years have seen a remarkable recovery in the nation’s economic fortunes. This, though, has come at a cost. The logic behind the increase tuition fees was to provide students with a better, and more accountable, style of university education. Instead, balancing the books has resulted in the victimisation of a demographic singled out for the fact they contribute ‘nothing’ to society, along with a shift in campus culture from quality of education to target-meeting.

While it is easy to dismiss students as a ‘political irrelevance’, Jeremy Corbyn’s successful election campaign for the Labour leadership was symptomatic of a generational dissatisfaction with a government - the Conservative Party - who no longer seem interested in them.

The image of philosophy undergraduates who spend three years of an undergraduate degree publicly subsidising their drinking through their student loans is enough to dissuade most people students should just ‘shut up and stop complaining’.

However, Corbyn’s victory demonstrates, not only the disconnectedness of the Tories towards students - but also just how dangerous this cohort is. Students cannot be ignored.

Twitter: @jsoomper

James Somper is a freelance writer and history undergraduate. He has written for The Telegraph and The Gentleman’s Journal

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments