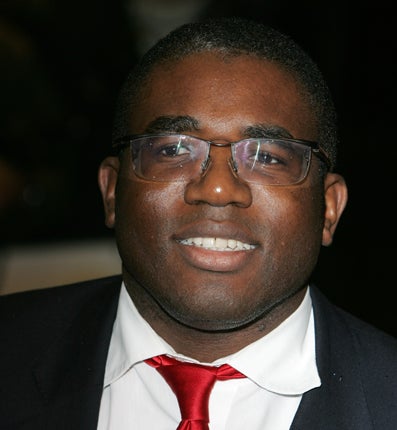

David Lammy: 'Do what is right for you'

Liz Lightfoot talks to the minister for higher education about his own experience of applying to university

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As he prepares the official response to this year's A-level results, David Lammy can clearly recall the emotions and tension of the run-up to his own day of reckoning. It was the summer of 1990, and he was holding an offer to study law at one of the country's leading universities, and it all rested on his grades for English, history and religious studies.

"I remember it well," says Lammy, now the minister for higher education. "This is a really nervous time for students and their parents. For me, the nervousness was wrapped up with a huge unfamiliarity because no one in my family had been to university."

It was a step into the unknown for the 18-year-old Lammy, whose parents had come to England from Guyana as part of the Windrush generation, and settled in Tottenham, north London, where he was born and now sits as a Labour MP. After his father left the family home, Lammy and his three elder brothers and younger sister were brought up by their mother on her salary as a care assistant and home help.

Church played a large part in their lives and it was there that his singing ability was recognised. He managed to secure a choral scholarship to the King's School, Peterborough, then the only state choir school in the country.

By his mid-teens he was a fan of LA Law, the television series, and decided he wanted to be a lawyer. "I liked the idea of advocacy and I liked the respect I thought was attached to the law," he says.

The idea took shape and the University of Nottingham offered him a conditional place in its law school. "University represented a very big departure because I had been in my school environment for seven years and developed a strong community of friends, and a strong relationship with teachers," he says.

"Going to university is a very new horizon. It is you, and you alone stepping into this place and the beginning of a really important stage of life. So [for me], the waiting was all caught up with this anticipation and excitement."

The waiting will have been even more fraught than usual for students this year, due to an unprecedented 10 per cent rise in university applications, representing an extra 50,000 people in the system. Many of those who fail to gain places at either their first choice or insurance university will enter the UCAS Clearing system to find courses with unfilled places. Each year about one in 10 successful applicants secures their place through Clearing.

Not all the students in Clearing have failed to secure a place. Some enter the system for other reasons, such as changing their subject or their choice of university. Lammy has a special understanding of the dilemma they face: his results sent his plans into a spin as they were better than predicted by his teachers.

Despite the high reputation of the University of Nottingham, he began to think about the possibility of a place nearer home. "I did not get an offer in London, and I had been away in Peterborough for seven years and wanted to come back," he says.

Thanks to the new Adjustment period, students will this year be able to scout for a different university if their grades are better then expected, with the security of sticking with their original choice should they fail to find a new place.

But, in the old system, Lammy faced the difficult decision of declining the place at Nottingham and chancing his luck in the Clearing system. After taking advice from UCCA – as UCAS was then called – and from his teachers, Lammy decided to contact King's College, London, which gave him an interview, as did the School of Oriental and African Studies (Soas).

He had only recently discovered Soas and had not applied there first time. He recalls: "I remember very well coming out of Russell Square tube station with my elder brother, who brought me to the interview at Soas, wearing a suit which was his not mine – probably shiny."

He chose Soas because of its international focus and ground-breaking courses, and says its global reputation helped him to secure a place at Havard University for postgraduate study.

As such, he thinks it is wrong to see the Clearing as a system for disappointed candidates; many using the service will have done better than anticipated. "Others will have come out of the school environment, had their summer holidays and decided their chosen course was not really what they wanted to do," he says.

And Lammy has some reassuring words for those worried about a dearth of places this year: "I am very pleased we have been able to an announce an additional 10,000 places and it is important to stress, as has been the case in Britain for as long as I can remember: if you have got an offer and meet the grades, then off to university you go."

Competition for places is nothing new, he says. Even in a normal year, without the pressure of extra students in the Clearing system, only around four in five are successful. About two in four re-apply the following year and, of those, 80 per cent are successful.

"It is right to say this will be a competitive year in Clearing but students shouldn't panic. They should think about the breadth of what is out there: over 140 universities that are very varied in their mission and a huge range of training institutions and Apprenticeships plus the Open University and Birkbeck, offering a wide range of part-time study."

Don't just do what is expected, do what is right for you, he tells students. "For me it was the right choice to study at a university in central London in close proximity to the Inns of Court which were very, very remote from my family background. It was a difficult decision at the time but it was the right choice and I have not looked back since."

Wise words: David Lammy's Clearing tips

Seek advice

"Teachers are very committed to the students they have taught," says Lammy. "My teachers were very helpful and certainly those in my constituency are around and keen to be in touch with universities to help them understand the strengths of students making new applications."

Contact UCAS

"I have been in very close contact and know they have around 100 staff manning the phones offering expert advice to applicants, their parents, colleges and universities," he says.

Don't delay

This is a competitive process – but don't rush into something before thinking it through. Where possible, visit the university or college.

Get you finances sorted – quickly

Seek out information from the Student Loans Company.

Other options?

If you don't get what you want this time round then look at other training and part-time study opportunities or reapply next year.

David Lammy: The CV

Born Tottenham, north London, 1972

Education The King's School, Peterborough; School of Oriental and African Studies; Havard Law School

1994 Called to the Bar

2000 Elected MP for Tottenham

2002 Joined the Government as junior minister for constitutional affairs

2008 Becomes the minister for higher education

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments