British basketball has done so much with so little but its potential has never been greater

The sport is under-funded but much-loved in Britain and that will always give it a chance on these shores despite the many obstacles, writes Vithushan Ehantharajah

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nick Nurse knows all about potential. More importantly, he knows how to unlock it.

He did so with the Toronto Raptors in 2019, leading them as head coach to the NBA Championship by creating a team that exceeded the sum of its parts in earning the franchise’s first rings and the city its first banner. Canada’s team rose to become more than just America’s add-on.

To get to that position, Nurse had to unlock his own potential first. That process began in middle England almost 30 years earlier.

In 1990, as a point guard out of Northern Iowa, he knew he wasn’t going to make it to the NBA. But he knew he had a shot, certainly a drive, to be a coach. So, aged 22, he took the punt to become a player-coach at the Derby Rams. And through the travails of a year dealing with the drop-off from Division One college basketball – and the perks that came with it – to small halls and a minibus driven by their starting centre, he came to one sure conclusion. What ambitions he had in basketball would be realised in England.

After going back to the United States, he returned to coach the Birmingham Bullets in 1995 and stayed for another 10 years. A stint with Brighton Bears was sandwiched between further returns home before a tenure as Great Britain’s assistant coach from 2009 up to the end of the 2012 Olympics. He moved onto the Raptors staff in 2013.

Read more:

- Lee Collins death: Yeovil Town captain dies aged 32

- England Euro 2020 squad: Who’s on the bus, who could miss out?

- England players must realise their power after passing up chance to protest over Qatar

- The making of Sam Curran, a quick learner who is wasted down England’s batting order

- How Olympic inclusion highlighted breakdancing’s cultural divide

After two decades of hopping back and forth across the Atlantic, few have a better gauge on British basketball. So, as Nurse stares down the barrel of the webcam while sat in the middle of the Raptors’ training court, The Independent asks him straight up: What, to him, *is* British basketball?

“It always, for a long time, seemed like there was a lot of potential talent and a lot of potential interest that always remained in ‘potential’,” he answers. “Probably because of the infrastructure. Not enough places to play, not enough coaching, not enough ways for people to earn a living on the administrative side, coaching side or the playing side to make it elevate to the level that the talent probably could take it.”

There is one caveat to this answer, which Nurse offers himself: He hasn’t watched a British Basketball League game in a while. And in a way, that makes it more salient. Because even if he hadn’t set eyes on a match since 2012, his assessment still rings true to this day – of potential that remains demonstrably unfulfilled.

The problems Nurse outlines are no closer to being solved and have been exacerbated by the pandemic. Justifying greater funding has been a long-running battle for the British Basketball Federation and Basketball England. Now with more sports desperate for funding due to the effects of Covid-19, basketball finds itself further back in a longer queue.

A boost came in December when the BBF were promised £1.35million as part of its placing on UK Sport’s Progression group for the 2024 Olympic Games. In February, Sport England allocated £2.5m in grants and loans, while England Basketball was given a grant of £200,000. The recent cash injections were to cover essential costs and ensure the survival of these organisations.

Facilities remain a top-down issue. Few professional clubs own their halls and renting indoor spaces because it is harder to justify further down the chain. The plethora of outdoor courts across the country helps the game tick along, but never more than that.

As for the British Basketball League (BBL), the main income streams through attendance have stopped creating a hole many fear will be too great to refill. Since the league’s formation in 1987, clubs have come and gone – there are currently 11 men’s and 11 women’s franchises – in part because of a lack of interest, both from the national media and sponsors. A two-year deal to return the BBL to Sky Sports struck last December is hoped to rectify the latter, but those within the league tell The Independent it will be a few generations before any real benefits are felt.

And yet, at the recreational level, the numbers show basketball as an undeniable force. Between 2018 and 2019, more than 1.3 million people in England played it at least once a week. During this period, it ranked as the second most participated team sport behind football.

Therein lies the problem: a huge disparity between raw interest and professional respect. To get into that, it’s worth splitting the subject into two parts that, for some reason, have not quite dovetailed – the BBL and British NBA fandom.

***

In 1978, Vince Macaulay was leaving class when a friend came up to him and begged him to make up the numbers in a basketball game. Having arrived back in Liverpool from Nigeria for his A-Levels so he could attend the London Institute of Film, sport was far from his mind. Basketball hadn’t even crossed it.

He agreed to stand around – they needed five to tip-off – but found himself taken by the game more than he thought. At the end a man watching from the sidelines came over and asked Macaulay if he fancied joining the local side, Liverpool Attack.

That man was Jimmy Rogers, a legendary coach regarded as the Godfather of British basketball. Rogers and Macaulay founded the Brixton Topcats in 1984, a club that became known for churning out talent. Their most notable alumnus is Luol Deng, who enjoyed a 15-year professional career in the NBA, primarily with the Chicago Bulls.

Many reflect on the 1980s as an unknown golden era for British basketball, where standards and interest were high. So much so that when the Topcats earned a Nike sponsorship in 1985, a 22-year-old Michael Jordan came down to grace Brixton Rec as part of the deal. Macaulay filmed and edited the footage of Jordan’s visit.

At some point over the next 15 years progress just, well, stopped. Macaulay, who became one with the scene as a player, coach and now owns the London Lions, has spent more than three decades exasperated as to why.

“This game, it’s incredible,” Macaulay preaches to The Independent. “And yet this country can’t see that. There are people outside this country who know our British players and we don’t. Luol Deng, next to Hamilton, is the highest-paid British sportsperson in history. He could walk down Oxford Street and no one would have a clue.”

If Macaulay’s organic discovery of the game tells one side, his professional life tells quite another. During his time at the club, they have been based in Hemel Hempstead, Watford, Milton Keynes and, since 2013, at the Copper Box as the first professional sports team to reside in the Olympic Park.

Their nomadic existence was down to circumstance: hiked rents requiring them to up sticks and find a new home, often ejected without regard.

Macaulay’s biggest gripe remains with finances. To this day, the words of Rogers, who passed away in 2018, still ring true to him and plenty of others. The biggest drop-off from grassroots comes through players assuming their own costs once they reach a certain level. Given the demographic of the majority who play basketball, it is a familiar ceiling.

“As far as Jimmy was concerned, selection for the national team was racist,” says Macaulay. “In that, if you got selected for England Under-18s, your mum and dad had to come up with £1,800. Who else is going to be able to do that unless they’re from X, Y, Z demographics? The national team don’t have enough money to pay for these things when it comes to travel and accommodation. So, you end up in this situation where kids who grew up with the game – primarily from ethnic, low socio-economic backgrounds – have to make a decision. And guess which way they go?”

One example that still rings in his ears is a situation with a player under his care in Milton Keynes called up to the England U18 side. With the national set-up unable to cover his costs, the club organised a fundraiser to get him on a flight out of Heathrow to play a match in Greece. Around the same time, a student in the player’s class was called up to represent the same England age group in rugby. He and his family were driven to Heathrow, where they stayed overnight before they were all flown out to Italy and back.

“You mention participation – we outstrip rugby and cricket but you look at how much funding they are getting, £50m here, £100m there. On what basis? Even netball, as successful as it seems to be, takes upwards of £20m from the purse. Fair funding is what we’ve always campaigned for the last five or six years. Can it get fair funding?”

Macaulay has tried to practise what he preaches at the London Lions. He has tried as best he can to invest exclusively in British talent, focusing on those in mainland Europe in a bid to bolster the Lions as a major continental force. Currently, the league allows teams to play a maximum of five over-18 non-British players per game, of which a maximum of four can be work permitted. British passport holders must fill the remaining spots.

Read more:

One of those he was able to coerce back to the UK was Justin Robinson - another product off the Topcats conveyor belt who earned a scholarship to the US where he went through the high school and college system. After a stint in Europe, he believed enough in the Lions project to return to London, where he grew up.

“I played in Europe for seven years and came back to England in 2017,” says Robinson. “There are a few Brits that came back before then but I took the leap of faith to come back and play in the BBL. It was a risk at the time because I was earning a lot more in Europe. Ever since then – I’m not even trying to toot my own horn – I think a lot more British guys are now here in their prime. There’s a list of high-level British players who came back then.”

Pay remains a stumbling block to attracting the best talent and thus elevating the most visible product. A middle-tier player at a higher profile club like the Lions, Newcastle Eagles or Plymouth Raiders could earn between £3,000 and £4,000 a month. Elsewhere, that bracket could be as low as £900. It has led to calls to establish a BBL minimum wage to ensure there is no exploitation.

“The players that have returned, even the players that are coming over from the US now – Americans – have found a way to make good money, make a career and make their base their home,” says Robinson. “Basketball over here is still trying to find a way. You need money to attract better talent. That will always be the case. “

***

While British basketball has struggled, the rise of the NBA has been unstoppable. The appetite for the game’s best players and a superstar lifestyle aligned with its cultural resonance knows no bounds on these shores, and on mainland Europe.

“When you think about Europe, there has never been a better time to be a fan,” says Ralph Rivera, NBA managing director of NBA Europe and the Middle East.

“Look at talent – the number of players from Europe has grown with around over 60 in the league. And they’re not just players; they’re the very best: Giannis Antetokounmpo (Greece), Luka Doncic (Slovenia). You’re talking about MVPs, Rookies of the Year. That builds on the “Big Three” of Tony Parker, Dirk Nowitzki and Pau Gasol who paved the way for players and fans from Europe.”

At the time of writing, there is only one active player on the NBA roster with a British connection – Toronto Raptors’ OG Anunoby, born in London but who moved to the United States aged four. However, a lack of representation has been no barrier to interest.

The UK is ninth in the world and number one in Europe for League Pass subscribers – a service that broadcasts all NBA games live, along with highlights and other content. An internal study within the NBA found the UK also has Europe’s largest online fan community.

It’s not for nothing that NBA Europe’s headquarters are also in London. That move came as a way of figuring out how to crack the UK market.

“In all of Europe, football is the No 1 passion people have,” says Rivera. “Outside of the UK though, when it comes to team sport, it’s basketball. What makes the UK market more challenging is there are so many other sports that have traction here in terms of fandom: rugby, cricket, Formula One, horse racing, even snooker and darts. There is a lot of fanaticism here in the UK, but there are also a lot of sports competing for that.” However, as the nine successful sold-out NBA London Games demonstrate, there is clearly a captive audience.

In a bid to get to fans earlier, the NBA teamed up with Basketball England to create the “Junior NBA”: sixteen leagues of 30 teams made up of mostly school-based 11 to 13-year-old boys and girls playing throughout a “season”. Part of the agreement includes harnessing the NBA’s clout with sponsors to assist with grassroots schemes like court refurbishments. The pandemic delayed the latest iteration but the drive is there to continue. Along with the hugely popular NBA 2K video game series, the belief at league HQ is the seeds have been sown for the next generation of UK super fans.

It was during the 1990s that the bug was caught in the UK and around the world. This breakthrough era was typified by the popularity of The Last Dance documentary, which revolved around Jordan’s final 1997/98 season with the Chicago Bulls. Channel Four were the first to ride the wave.

Read more: The Last Dance is an enthralling journey through Michael Jordan’s career

The broadcaster happened upon the rights to a McDonalds four-team exhibition tournament in 1995, which featured the Houston Rockets as defending NBA champions. Channel Four saw an opportunity to take the plunge and decided to go all in. They opted for a three-pronged approach of live-action (NBA XXL), a Thursday-night Match-of-the-Day wrap-up of the previous round (NBA 24/7) and a magazine show that encapsulated broader themes (NBA Raw) of music and fashion. Along with seasoned experts, they decided to bring on a presenter to act as a conduit between the league and an unfamiliar British public. Someone who could supplement basketball expertise with a strong knowledge of black culture. That was Kiss FM host and assistant editor of Blues and Soul Magazine, Mark Webster.

“We very deliberately went out of our way to not talk to people like they were kids,” says Webster, who spent half his year based in New York to tie in with the post-season. “But equally, we had to give people access to it. We were big on graphics and fast-editing: a very stylised production. We were making sure we provided information but not overwhelmingly so, which is easily done with American sport.”

The gig would only last three seasons as Channel Four lost interest and Channel Five picked up the scraps. The time differences and scheduling were seen as too great to overcome.

A shot in the arm came with social media. The NBA’s deliberately lax attitude to video rights in the 2010s allowed them to increase their reach. Twitter, YouTube, and, latterly, Instagram and TikTok became outlets for fans to indulge their passion and, in turn, content creators emerged to fill the gaps in traditional media.

One of those was Mo Mooncey, London-born, Midlands raised, who developed an affinity for basketball through family in the US and video games. Late nights and telling WHSmith to reserve one of the few copies of SLAM magazine for him were ways to scratch an itch, along with playing where he could. He began writing about basketball while at university and eventually developed his own channel – Hoop Genius – where he posted videos. Other video opportunities arose and, by 2019, he was on the radar of Sky Sports who were looking to revamp their NBA coverage.

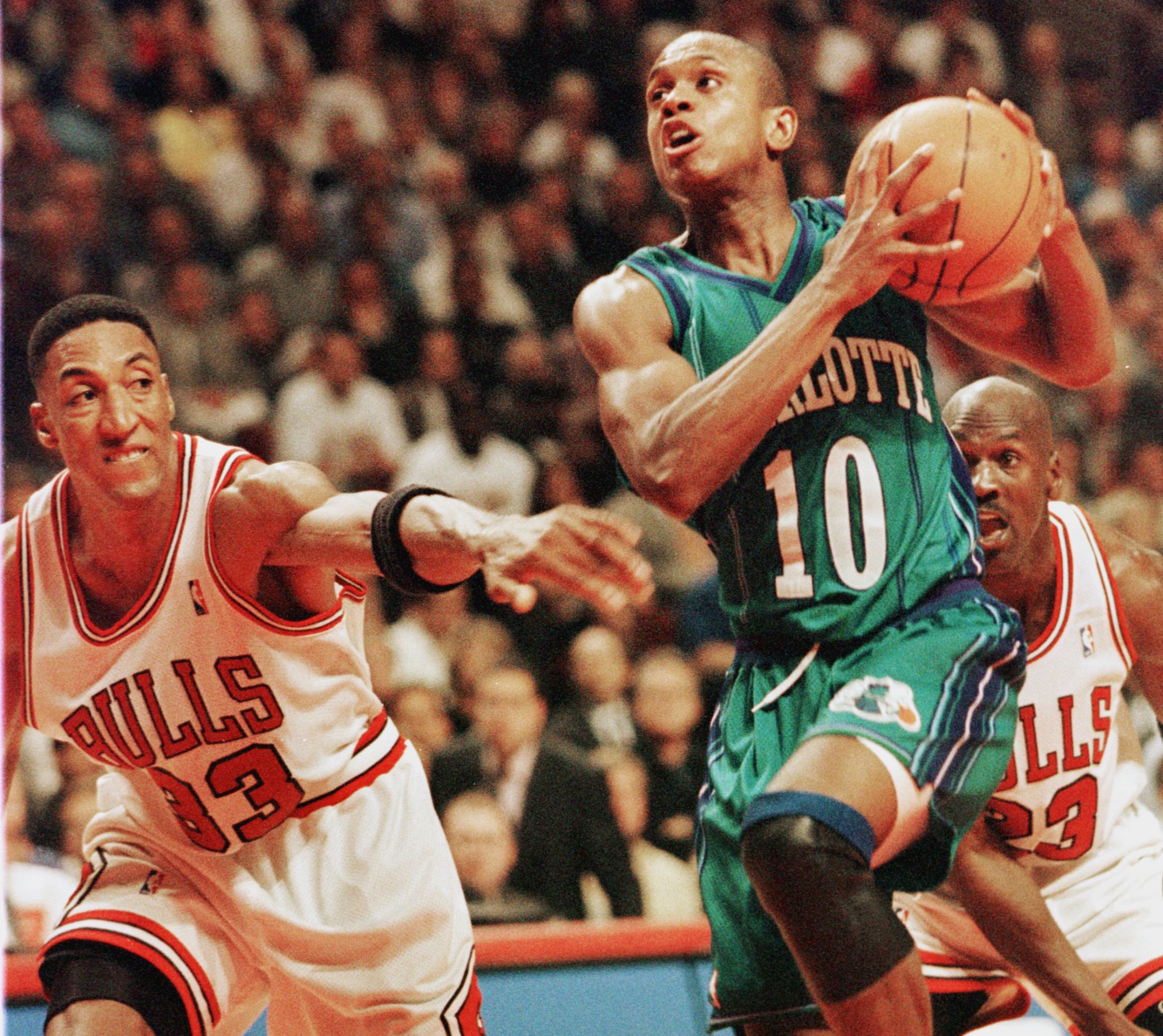

Mooncey is now in his second season with Sky, where ratings are up by 47 per cent this season, and is one part of a four-pronged presenting team with host Jaydee Dyer, British basketball player Ovie Soko – more widely known for his appearance in 2019’s Love Island – and former NBA all-star B.J. Armstrong, a three-time Championship winner with the Bulls in the early nineties. Their coverage is a balance of casual, engaging and considered, catering to a new breed of UK fan with a greater appetite for analysis. Combined with a drive over the last seven seasons to broadcast weekend games in UK primetime, the league has never been easier to follow.

“By the time Sky called, I felt I was established on the UK scene,” says Mooncey. “I can’t remember exactly, but I said to them, look, you’re not going to find someone who knows about the NBA more than me. I don’t mean this in an arrogant way, but I’d been so deep in it for so long. It was basically my life.”

As a representative of this “internet boom” generation, he’s got a few ideas on basketball’s recent accelerated popularity. “It’s really exploded in the last few years because it’s such an easily digestible game on social media. You can watch a Steph Curry three or a LeBron James dunk. It’s easily accessible. Every night there’s anywhere between two and 12 games. Within each game there are hundreds of highlights. In football, you might wait a week and then there’s only one goal.

“I think it’s going to have a trickle-down effect. When people of my age – 26 – and younger, when we’re grown up and raising kids, we’ll be showing our kids the NBA in the way that our parents showed us football, cricket or rugby.”

It’s on the subject of the BBL that Mooncey switches from optimism to despair. “British basketball is awful. You don’t really become a huge fan. They still don’t know how to grab the next generation and develop a fanbase. There are kids running Instagram pages that do a better job of pushing the BBL.”

Sky’s BBL coverage has helped boost this side. Teams and players have noticed upticks in social numbers and engagement. The better production value that comes with a television broadcast has been welcome, though the majority of games are still streamed via a standstill camera at centre-court turning left and right, which lacks court-level views and does not catch the facets that make basketball so dynamic, such as the physicality and athleticism under the rim.

Everyone involved with British basketball knows better funding will lead the sport to a better place. They also agree greater respect will be driven by what’s on the court. However, which court offers the surest platform remains a sticking point. Mooncey believes it needs to happen on the pristine wooden floor at the highest level.

Read more:

“What will make it big here is if we ever get a British kid as a NBA superstar. Not just a ‘good’ player, I mean on a level of going and doing what Doncic does. That’s what really explodes it. I started playing rugby after that 2003 World Cup. Those peripheral sports need that kind of moment in order for it to explode.”

While that would fill a void that has never really been filled – Deng, even as a high class albeit second-tier NBA talent, remains an outlier – the roots of that player need to be unequivocally identifiable as a British product. The issue here is that there is no discernably British way of playing basketball. Not yet, anyway.

“I saw two distant styles when I was over there,” recalls Nurse. “The domestic game at the time was fast-paced, under-sized and athletic. The international game was a lot of guys playing in Spain, Italy. We had a lot of size so we could play a lot of the European style set-offence, set-defence. A little bit more physical, not as much fast-paced.

“The contrast is hard to overcome, but we didn’t have all that many players from the BBL that were playing on the national team. Most of our guys were already playing on mainland Europe so they were used to that style.”

Of course, there is no “right” way to ball, and certainly no “wrong” way to win. But the prevailing sense is the need to cultivate an identifiable way of playing. Thus the quandary becomes very chicken and egg around success and style.

“If I look at an American player I can tell you if he came from Los Angeles, Chicago or New York, because they play differently,” states Macaulay. “Someone from Chicago will take the ball to the basket because it’s too windy to shoot long. An LA baller is very laid-back, often quite flamboyant. If you come out of New York, you’re generally hard-nosed with incredible ball-handling skills and a relentless way about you.

“We don’t really get any of that in England, say. Our main influences come from America because what talent we have leaves during their formative years for the States and they develop their styles over there .”

For Robinson, who has experienced a variety of styles that, at 33, are as much his personality as his game, the lack of a “British way” is a product of the stunted growth.

A final question is put to him: Is it possible for him, and other higher profile British players, to elicit a cultural shift?

“I don’t see it as a responsibility because I just want to be myself. And show the younger up and coming British players that you can play at home and make a career here. That, I think, is our main role as active players right now. We need to continue trying to show the UK is a place where our basketball and your basketball can thrive.”

What certainties there are in British basketball rest in the countless individuals pulling the game along as a collective. Doing their utmost to prop the sport up and champion its worth all while trying to do right by themselves. Any spare time and energy is taken up by administrative stand-offs and philosophical considerations of what they do, but never why they do it.

That, ultimately, is the great frustration with British basketball. There is no lack of effort, simply a lack of what they deserve. The absence of provisions is covered by raw passion. And as unsustainable as that may be, talking to those involved with the sport leaves you with the impression that even if it continues to be underfunded, it will never be under-loved.

It may seem churlish to suggest the government and wider sporting authorities are actively keeping basketball down. But by being so passive to its evident grassroots enthusiasm is to be complicit with its struggles.

Basketball by its very essence is about making the most of very little. All you need is a ball and a hoop. Extra help in the UK can see it discover itself and become a product everyone can be proud of, not just those with basketball in their blood. Even after decades of neglect, basketball’s potential has never been greater.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments