Tour de France 2019: Bidons and body armour - how the biggest race on earth is dealing with the heatwave

With near-record Tour temperatures of 40C in the shade and 60C on the road the world's best cyclists are having to take drastic measures to cope

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s halfway through the stage, and Team Ineos have a problem. Geraint Thomas’s earpiece crackles with news from a team car behind: “We’ve run out of bidons,” he’s told. You know conditions are bad when the world’s most meticulous sports team runs out of water by 2pm.

Ineos had loaded the car with 10 bottles per rider in preparation for a scorching day in the south of France, with near-record Tour temperatures of 40C in the shade and 60C on the road. But it wasn’t enough, and they weren’t the only ones. “I had one full bottle,” a blowing Peter Sagan says afterwards, “and another, and another, and another, and another. It was crazy.”

All around, riders are doing everything they can to cool down. Ice cubes are crammed in helmets and stuffed inside unzipped jerseys directly on to matted chest hair. The Kiwi George Bennett takes a chilled bidon and jams it down his back. By the end even the man in the yellow jersey, the infallible Julian Alaphilippe, is cooked, going straight from anti-doping to his bus and skipping media duties due to dehydration.

Before each stage, bottle distribution becomes an event in itself as teams plot points to dish out water as well as some electrolyte mix, to combat the loss of sodium through sweat. In the race the peloton takes matters into its own hands, snaking across to the side of the road guarded by trees or a few shop awnings. Afterwards team doctors weigh the riders and have the glamorous job of assessing the colour of their urine.

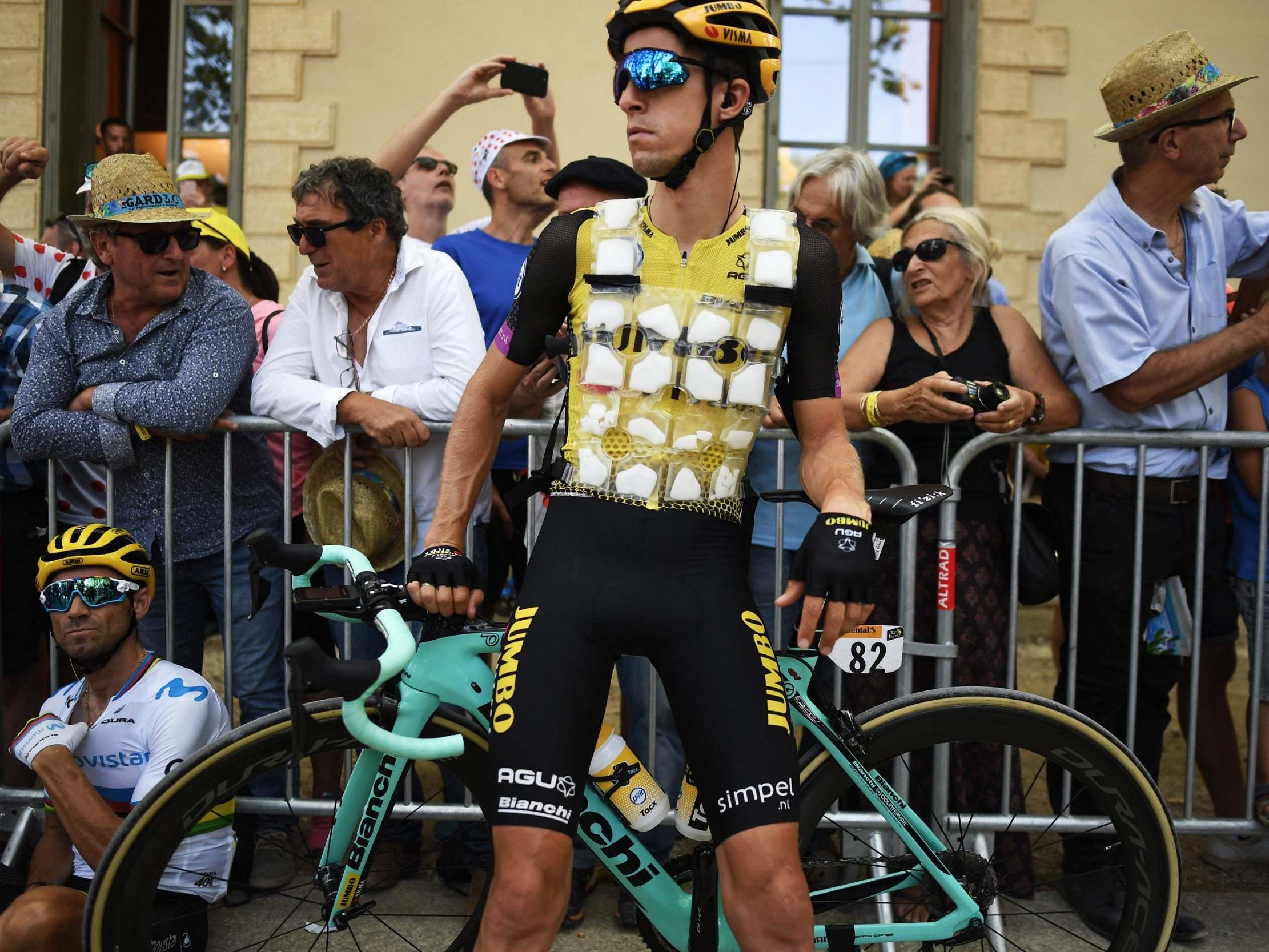

A walk around the paddock reveals some of the more technical heat-battling strategies. Team Arkea-Samsic are topless on their warm-up bikes except for their specially designed ‘cryovests’, a little like body armour but with ice instead of Kevlar. As he steps off Ineos’s bus, Luke Rowe slides a pack into one of his ice-socks, then the other, then pokes one down an unsuspecting colleague’s neck. In a few hours he will have been disqualified from the race for taking things too far; later he will blame the heat of the moment.

The weather has created something of a debate here about some the fundamental values of the Tour de France. Should riders be protected from the dangers that come with riding hard for five hours in 40-degree heat? Or are the extremes exactly what makes the race one of sport’s greatest endurance events? Both points are valid, but there does seem something slightly sadistic in watching them boil.

It is times like these, when the body temperature rises and the lungs burn, that illness ravages the peloton. By week three it is not just the mind and the legs but the immune system which wants to switch off and sleep for a month. Teams have to be ruthless and riders who fall sick are put in quarantine – sleeping separately, eating in solitude, not even a handshake allowed. Ineos are said to take germaphobia to extreme levels, treating each evening’s hotel check-in like entering an operating theatre.

Thibaut Pinot, France’s darling who is now the bookmaker’s favourite to win the race and end 34 years of hurt, has his room specially cleaned every day, according to L’Equipe. He’s been made to take regular sauna sessions to get used to the heat he hates riding in – he doesn’t like much outside fishing in a pond near his house – and every day he’s wrapped up in a long-sleeved jersey at the end because his team want him to sweat.

Extremely hot weather is not exactly a new phenomenon in cycling, of course. The Spanish grand tour typically starts in August, which always seems a little cruel, where particularly in the south the Andalusian sun can often be brutal. And for those who hail from hotter climes, this Tour de France is positively mild.

“It’s similar heat to what we have in Australia at the Tour Down Under,” says Matt White, head of Australian team Mitchelton-Scott. “It’s warm, but the guys just have to pay a little more attention to their hydration. More bottle points, they come back to the car for more bottles, ice socks, just be a lot more aware of the temperatures they’re racing in.

“This is probably the hottest day a lot of riders have experienced this year, but some of our guys have been training in Sierra Nevada and Grenada, where there’s temperatures like this nearly every day.”

Yet for others, it’s too much. Sagan, who is on the verge of clinching a record seventh sprinter’s green jersey, complains it is like “rolling in an oven”. He says: “If we have to go to the mountains (in this heat) it will be suicide. I think CPA [the riders’ association] should do something. I don’t know why we pay them when they don’t protect us.” Later race organisers announce that the following day’s time cut will be more lenient to account for the heat.

But as ever in cycling, the show must go own. The riders will require more detailed strategy and basic ice shovelling to avoid sunstroke, dehydration and illness, as one of the most absorbing races in years kicks up into the Alps for its grand finale. On the plus side, conquering some of the hardest climbs in Tour de France history is just another small problem on their list.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments