The cult of Roger Federer: What is it that inspires such obsessive devotion?

Tennis star Roger Federer inspires adoration in his fans, whatever their age or status. Will Skidelsky, a self-confessed obsessive and author of a new book on the champion, explains how following the Fed is like belonging to a religion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Roger Federer is making serene progress through the early rounds of the French Open, his 62nd consecutive Grand Slam tournament. This August, he'll turn 34. According to the rankings, he's the second best tennis player in the world. Talk of retirement has trailed him for years, but he insists he's not about to hang up his racket. And who can blame him? He's injury-free, mostly still playing well – and challenging for the major titles, if no longer winning them. Professional tennis is his life, what he knows. Why should he hasten to the exit?

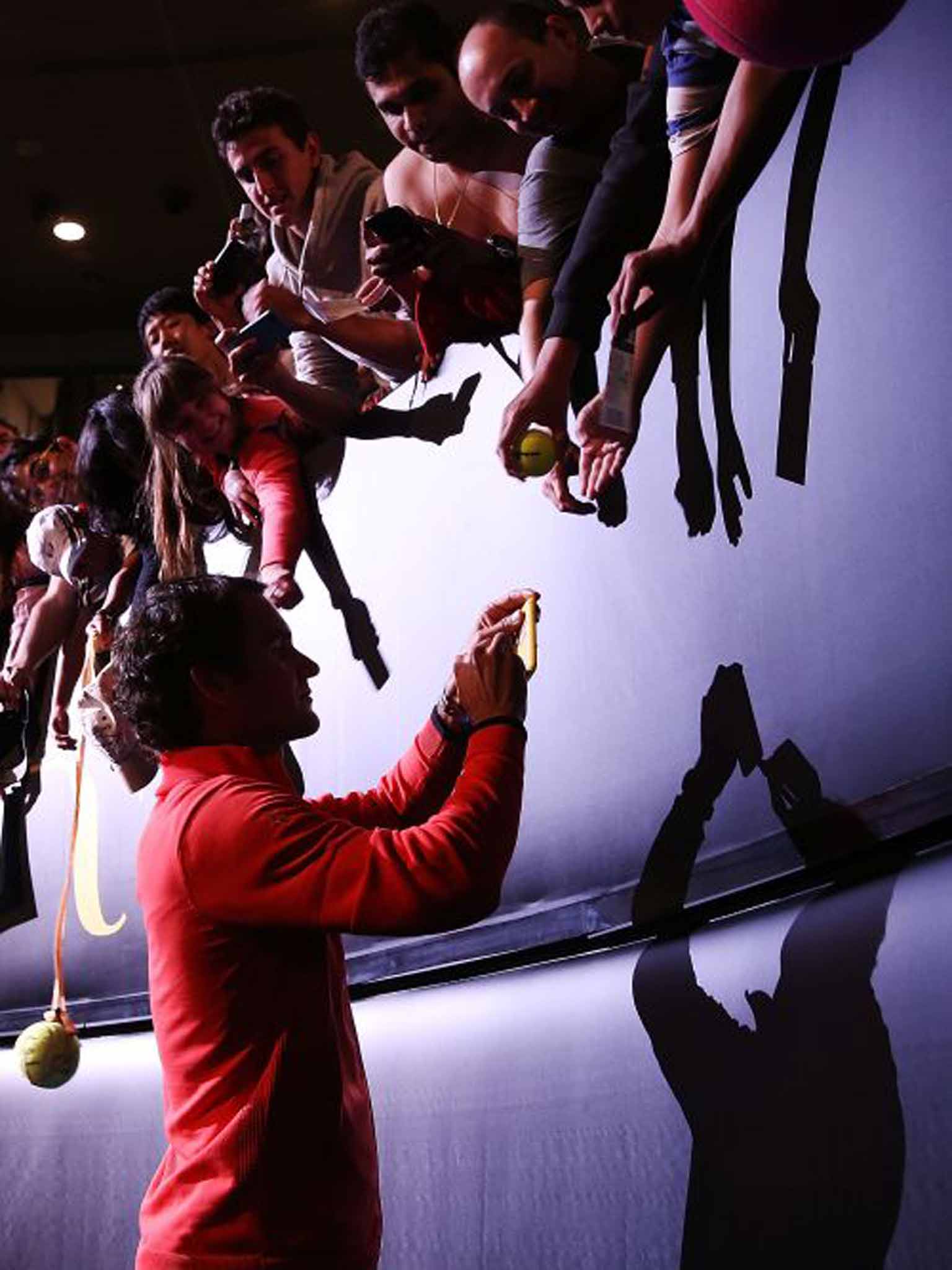

I came to Federer later than many: my fanship took hold in late 2006, when his days of real glory were already behind him. Ever since, he's been a constant in my life, part of my psychic make-up, my identity. And this protracted quasi-love affair has taught me something, which is that I am far from unique. A great many people harbour similarly intense, often positively deranged, feelings for Roger Federer – although most refrain from pursuing him onto the court itself, as one selfie-hunting fan did at Roland Garros a couple of days ago.

Of course, it's no secret that he's immensely popular. Wherever he plays, crowds treat him like the home favourite. He's won the ATP Fans' Favourite award every year since 2003. He's one of the most marketable, and rich, athletes in the world, earning around £40m a year just in endorsements. Yet a word like "popular" doesn't quite do justice to the adulation that he inspires, doesn't quite capture its all-consuming nature. For most, if not all, Federer fans, supporting him is about more than mere admiration, more than affection. It tips into something deeper, less definable. It's practically a way of life. You could call it a quasi-religious feeling, as much a question of belief as love.

David Foster Wallace was among the first to diagnose the phenomenon, in his 2006 essay "Federer as Religious Experience". According to the late American novelist, the Swiss star's defining feature was that he regularly hit shots that violated the laws of physics, that were "impossible". He famously described these as "Federer Moments".

I think this terminology is very apt for the passion that Federer inspires. His fans definitely regard their idol as being the vessel for some higher power, something lying beyond ordinary comprehension. It follows that watching him is almost a form of religious observance. Mute reverence is the only correct response. "Shh, genius at work," reads one of the signs that his fans hold up.

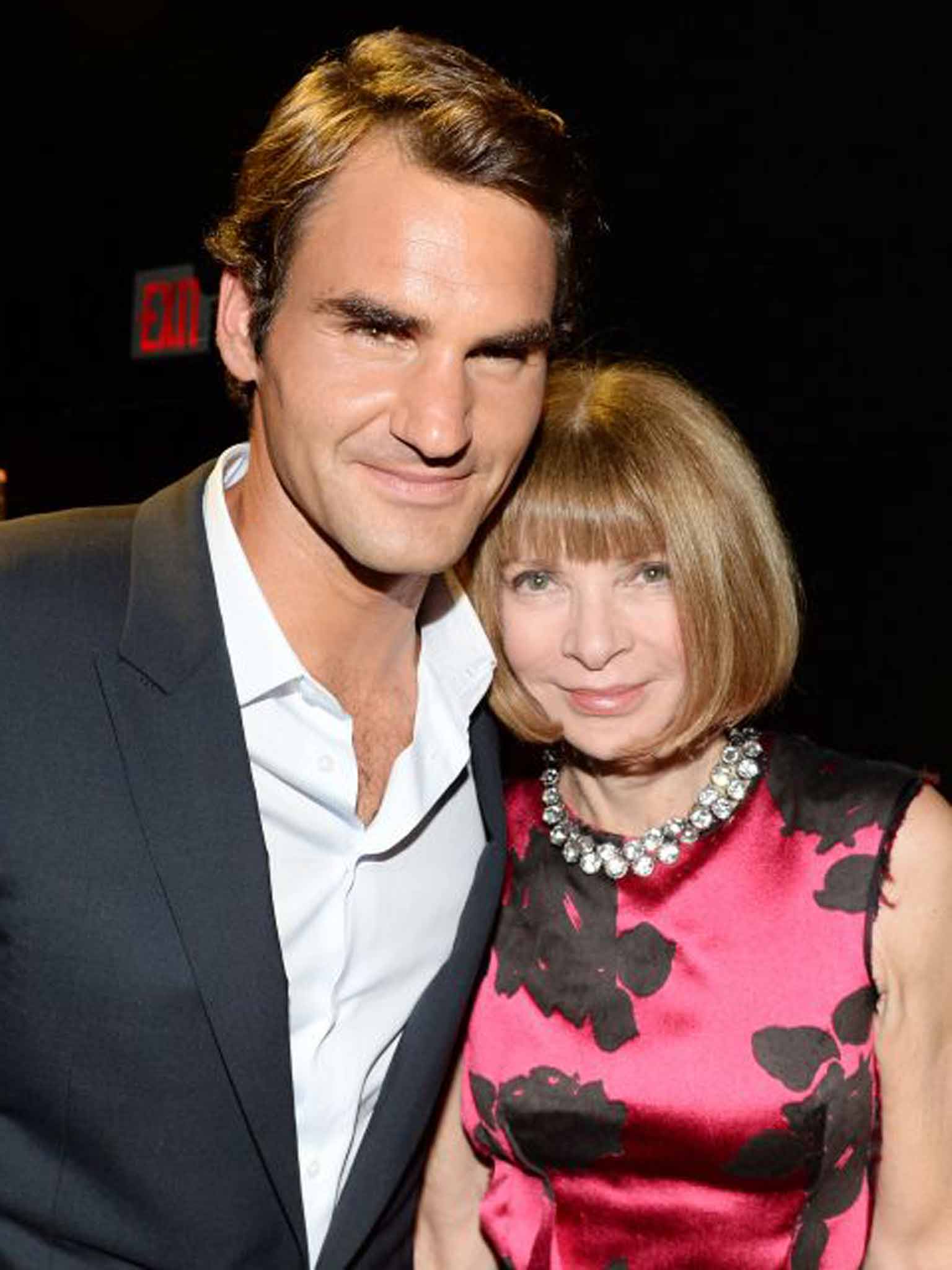

What also follows is that being an ardent Federer fan feels, at times, like belonging to some vast cult, with members scattered all over the place. Wherever you go you'll encounter people who've been similarly touched, who, like you, have seen the one true way. If Wallace's essay on Federer is the cult's founding text, then Anna Wintour, the editor of US Vogue, a good friend of Federer and for at least a decade an obsessive watcher of his matches, may well be its high priestess.

Partly because of writing a book about Federer, I've become very aware of these fellow obsessives, just how ubiquitous they are. They can, I've discovered, crop up anywhere. Sure, you'll find them in the expected places: at tennis clubs, in the stands at his matches. But I've often encountered them in less obvious locations. At smart dinner parties, I've met high-powered bankers who, the minute Federer is mentioned, drop their guard and come over all weepy and rhapsodic. I once took a ride from a taxi driver who confessed that he felt more strongly towards Federer than he did towards his own wife. At the public courts near where I live, I met a Polish man so obsessed with the Swiss that he'd taught himself to play in the exact same style, spending countless hours in front of slow-motion shots of his idol, racket in hand. (He also – of course! – named his first son Roger.) Unlike Nadal fans, who tend to be in their teens or early twenties, Federer fans, I've found, can be any age: I've met 10-year-olds and octogenarians who adore him, although the largest number seem to be middle aged (for reasons I'll get on to). They can be from any country and straddle every social class. There really is no one type.

What explains the hold that Federer has over so many? One thing I'm confident about is that it doesn't have all that much to do with his personality. Sure, Federer, at a personal level, is known for being exceptionally nice. He's polite to (and about) everyone (except the odd opponent he's lost to). He has impeccable manners and exhibits remarkable patience in dispensing his many obligations. He's a great "ambassador" for the sport. Not everyone likes him. Many regard his affability as masking a core of extreme arrogance (they may well be right). Some think him ungracious (his speech upon beating Andy Murray in the 2012 Wimbledon final was considered particularly patronising). When describing his own game, he has a fondness for adjectives like "amazing" and "incredible", which strikes many as embarrassingly immodest.

But I've always been tempted to laugh when people ask me: "How could you be so obsessed with Federer? Isn't he a bit of an idiot?" (They don't always put it as nicely as that). Because for me – and, I suspect, for a great many of his fans – what his personality is like isn't really the point. This isn't personal, I want to say; it's about the tennis, stupid! Federer seduced me, all those years ago, with the majesty of his game, which struck me as being like the physical manifestation of some Platonic ideal of truth, of beauty. His tennis called out to me – and, powerless to resist, I answered the call.

But what is it exactly about that tennis? Sure, the miraculous moments – the "tweeners" (when he hits the ball between his legs), the ridiculous angled passing shots, the stupefying drop shots – are an important part of the picture. But in a way, they're merely the baubles, the cosmetic add-ons. There's a deeper truth to Federer's ascendency, one that brings into play the entire history of the sport. The fact that Federer is particularly loved by those in the 35-55 age bracket is surely no coincidence. This is the demographic who will have witnessed the changes to tennis wrought by racket and string technology over the past four decades. The shift from the relatively spinless, gentle and crafty game of the Seventies to the ferocious, bruising power game of today has been profound; no other major sport has had its basic character so altered during this period. These changes can't be undone, and there is no point calling for a return to wooden rackets (as John McEnroe periodically has). As is almost always the case, technological progress has resulted in some things (craft, finesse, elegance) being lost and others (power, speed, excitement) being gained. It's simply impossible to say whether today's matches are "better" to watch than the matches of 40 years ago: the context is so different as to render the comparison meaningless.

One of the key components to Federer's appeal, I believe, is that his game would be impossible to position on a graph delineating all the changes of recent decades. Players such as Nadal and Djokovic are easy to place; they are emphatically of the here and now. There is nothing remotely old school about them. (In Nadal's case, "futuristic" might be even more apt.) Federer is sometimes described as a "throwback", but the truth is more complex.

His game is both contemporary and old-fashioned, modern and classic. In his movement, in certain technical features of his shots, in his side-on gracefulness, he certainly does recall pre-graphite days. But in other respects – his power and stamina, his ability to generate staggering topspin – his game is wholly modern. This epoch-straddling ability is something many great athletes possess, but his seems particularly remarkable, given how different the game's recent eras are from each other.

This backward-facing character is a significant source of emotional power. Ours is a culture obsessed with progress, with improvement, and sport is a major focus for such sentiment. (Aren't athletes always getting fitter and stronger, records always being broken?) Someone like Federer is a counterbalancing influence. He seems to reconnect the game with its history and, for spectators, this can be a source of immense pleasure. Watching him, I often feel as if I'm being transported back to my own boyhood, to the game I loved (and ultimately abandoned) as a child. He has the ability to take me out of myself, to take me to other times, other places. For this, I will always be grateful.

Naturally, the Federer narrative has other strands to it; how could it not in such a long and varied career? When Wallace wrote his essay in 2006, Federer was at the top of his game, without serious challengers. In the ensuing nine years, his fans have witnessed the spectacle of his superiority being first challenged and then eclipsed. Rafael Nadal, of course, was the man responsible for bringing Federer's ascendancy to a close and, in a way, we Federer fans should be grateful to him for this (although we can't bring ourselves to actually like the Spaniard). For out-and-out dominance always gets boring in the end. All great athletes need equally strong rivals. And how strange – but also fitting – that Federer's greatest rival should have been a man who is the negation of everything he stands for, a diametrically opposed ideal of sporting excellence. Whereas Federer stands for effortlessness, lightness, natural talent, beauty, Nadal stands for effort, strength, determination, the overcoming of impediments. This is why their rivalry was so spellbinding, although, in truth, it was a short-lived thing. Like countless others, I found the spectacle of Federer desperately trying to cling on to his superiority – as, for example, in the 2008 Wimbledon final – impossibly riveting and moving. It was as if the pair were battling for the very soul of tennis.

As the years have passed, another element to Federer's appeal has emerged: sheer longevity. Initially, what was counter-intuitive about him was that he could exist, playing the tennis he did in the modern era. But more recently, he's defied the odds in a new way: by carrying on competing at the top. The received wisdom is that he should be past it by now, enjoying time with his family, his stupendous wealth. After all, in the bruising modern era, isn't tennis really a game for younger players, those in their mid-twenties? Pundits, certainly, have written him off many times, responding to each dip in form by prophesying the end. But still he keeps on going. Just the other day, he even predicted that he planned to play on well beyond next summer's Olympics in Rio. Remarkably, he still hardly ever gets injured. And though it's true that it's now nearly three years since he last won a Grand Slam, he remains very much on level terms with his other "Big Four" rivals.

Tennis fans of all stripes endlessly debate the question of where Federer stands in the game's overall hierarchy – of whether he really is the greatest, the "GOAT". Personally, I think such debates are pointless. For one thing, just as the game of today can't meaningfully be compared to the game of 40 years ago, so it's impossible to pit the achievements of a Rod Laver, or a Bill Tilden, against those of a Federer or Nadal. The circumstances are just too different.

But I'd question the usefulness of such comparisons in another sense. Doesn't Federer, as an athlete, stand for something opposed to the very idea of quantification, of measurement? To reduce his career to mere numbers, mere logic, is to fundamentally misunderstand what he is about. Questions of how good he is can't and shouldn't be resolved rationally, for these are ultimately questions of faith, of belief. So – can I say for certain whether Federer is the greatest player of all time? No, I can't. But do I believe him to be the best? Yes, emphatically. µ

'Federer and Me: A Story of Obsession' by William Skidelsky is out now (Yellow Jersey, £13.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments