The amazing tale of tennis and the Titanic

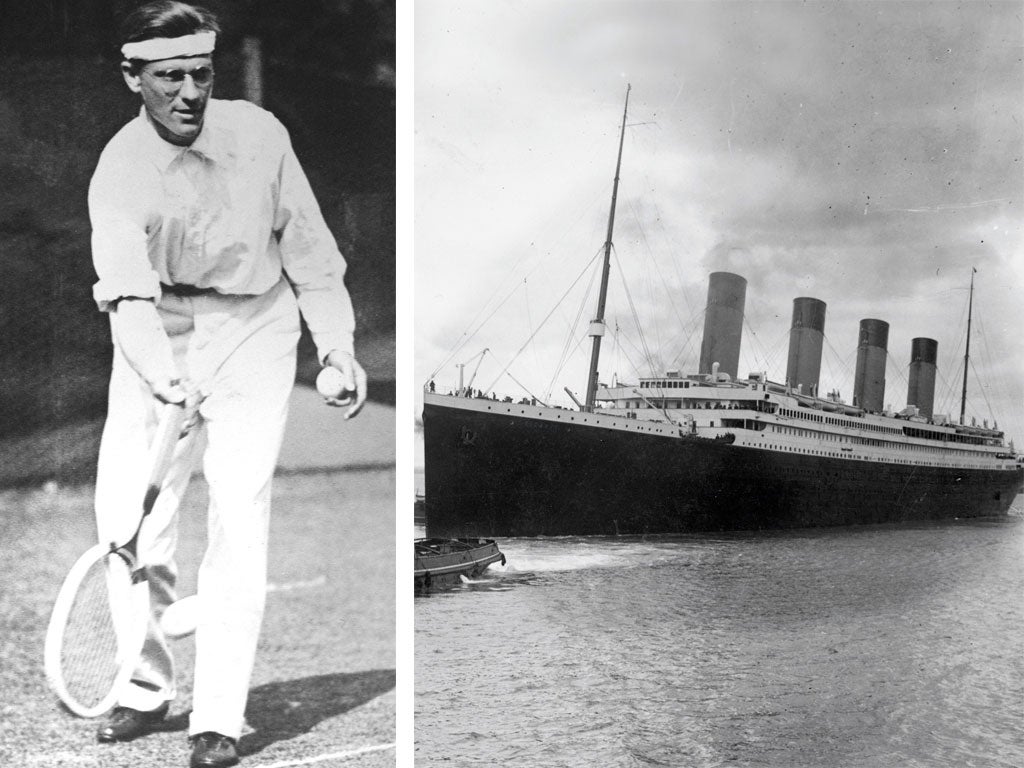

Dick Williams and Karl Behr were elite players who met on court after coincidentally surviving the 100-year-old disaster

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For Dick Williams it must have been a message as chilling as the icy waters in which he had spent several hours the previous night. Williams, a 21-year-old American tennis player of great potential, was on board the Carpathia steamship, having been rescued from the sea following the sinking of the Titanic. A doctor examined his painful legs, which had turned purple, and said they had been so damaged by the cold that amputation might be necessary.

By an extraordinary coincidence, another of the Titanic's survivors on the same rescue ship was 26-year-old Karl Behr, who had represented the United States in the 1907 Davis Cup final and had lost in the doubles final at Wimbledon in the same year. Behr was in a better physical state than Williams, having been one of the few to escape in a lifeboat. The two men met for the first time on the Carpathia.

While Behr helped survivors – Williams later said that his fellow tennis player had shown him great kindness – Williams walked up and down the deck in what proved a successful attempt to restore circulation to his aching limbs. "I'm going to need those legs," he reportedly told the doctor, who had feared gangrene.

Six weeks later Williams played in – and won – a tennis tournament. Even more remarkably, Williams and Behr met on court for the first time later that year and again two years later at the US Nationals, the tournament that became the US Open. Williams, one of the finest players of his era, went on to win the Davis Cup five times, the US Nationals twice and the Wimbledon doubles. Both men were inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

The story of Richard Norris Williams II and Karl Howell Behr, who became friends, remained untold for decades, but the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic, which embarked on its fateful voyage a century ago this week, has coincided with the publication of two books, Starboard at Midnight, written by Behr's granddaughter, Helen Behr Sanford (better known as Lynn Sanford), and Titanic: the tennis story, by Lindsay Gibbs.

Although they first spoke on the Carpathia, Williams had recognised Behr on the train both had taken to Cherbourg, where they boarded the Titanic. Behr was a leading American player who in 1907 had partnered Beals Wright in the Wimbledon doubles final and the Davis Cup final against Australasia. On both occasions they lost to Norman Brookes and Tony Wilding.

A lawyer, Behr was returning to New York on the Titanic from a business trip. He took the ship in order to pursue a romance with 19-year-old Helen Newsom, whom he wanted to marry. She was travelling with her parents, who had taken her away on holiday because they had yet to give their approval to Behr's courtship.

Williams was an American citizen but had been born and raised in Geneva. He and his father, Charles Duane Williams, a descendant of Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of the United States, were heading for a new life in America, with his mother due to follow later. Dick was to study history and geology at Harvard and was also hoping to develop his tennis career.

At 11.40pm on 14 April 1912, four days after the Titanic left Cherbourg, the "unsinkable" vessel struck an iceberg. Before the ship foundered less than three hours later, Behr, his future wife and her parents boarded a lifeboat.

There was a "women and children first" policy, but Behr was asked to help row the half-empty lifeboat number five by J Bruce Ismay, managing director of the Titanic's owners, who was on board for her maiden voyage. Ismay, who also survived, was later vilified in the press and labelled "Coward of the Titanic" for his behaviour on the night. Just 700 of the 2,200 passengers and crew survived.

A report in the Newark Evening News six days after the disaster quoted Behr. "At that time we supposed there were plenty of lifeboats for all the passengers," he said. "One of the ladies asked Mr Ismay whether the men could go with her. I heard Mr Ismay reply quietly: 'Why, certainly, madam.' We all got into the boat. Even then it was not filled and Mr Ismay ordered an officer and two or three more of the crew to join us."

Meanwhile, Williams and his father had been helping passengers into lifeboats. After the last had been launched, they went to the captain's bridge. With the ship about to sink, a giant funnel tumbled down, killing Charles Williams. His son, having jumped out of the way, leapt into the sea. He joined about 30 passengers who clambered on to a collapsible lifeboat which had not been assembled. The freezing water came up to their waists and by the time the Carpathia arrived all but 11 of them had died.

Today the two men are remembered with great affection by their families. Lydia Griffin, Williams' granddaughter, knew him well. He died in 1968, aged 77. Sanford was born six months after Behr's death in 1949 at the age of 64, but remembers her grandmother and spent 10 years researching her book, much of which is based on a 185-page memoir written by her grandfather.

Both granddaughters talk of the men's dignity and stoicism. "He was modest and humble," Griffin says of Williams. "He was a very under-stated, very dignified person. He would be horrified that we were talking about him now. It was a different time. People didn't wear their hearts on their sleeves the way people do these days."

Griffin believes the vascular and circulation problems Williams suffered in his later years were probably a legacy of his time in the freezing water, though he never said as much.

"He never talked about his Titanic experiences or his tennis experiences," Griffin said. "He had all these wonderful trophies that he had won, but his view of them was practical. We carved our Christmas roast on his Wimbledon platter. The trophy he won from winning a championship in Switzerland became a crayon box when we were children."

Sanford recalled only one conversation with her grandmother about the Titanic. "I asked her about it when I was 12," she said. "She was completely silent for a long time. It looked to me like she was miles away. She eventually said: 'I'm sorry, I can't talk about it.' What she did say was that the worst part for her was on the Carpathia."

Griffin never talked to her grandfather about the Titanic. "We knew it was something that should not be discussed. He had watched his father crushed by the steam funnel. It was a horrible personal tragedy for him. He was very close to his father."

Four years after the disaster, Behr suffered a physical collapse and spent time in a sanatorium. Sanford believes he suffered from "survivor guilt", particularly as he had escaped in a lifeboat. "He never said he felt guilt as a survivor – he would never have admitted that – but I came to that conclusion," she said.

Any anguish Behr felt was probably heightened during the First World War, when he was told he could not serve in the US Army because of his German ancestry. A great patriot, Behr was a friend of Theodore Roosevelt and organised the Great Preparedness Parade in New York in 1916 in support of American involvement in the war.

Williams enlisted in the US Army in 1916. An artillery officer based in Paris, he was awarded France's Croix de Guerre and Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur and got to know many of the conflict's central characters, including Marshal Pétain, the French war hero later branded a traitor for heading the Vichy regime.

Both Behr and Williams went on to be successful financiers and both showed great commitment to public service. Williams became director of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Behr married Newsom in 1913. Williams' first wife died in 1929, 10 years after their wedding, and he remarried the following year.

Sport remained an important part of both men's lives. Behr won their first meeting in 1912 – a marathon five-set match at the Longwood Bowl which was Williams' first defeat on American soil – but the result was reversed in the quarter-finals of the US Nationals two years later. That was the last time the tournament was played at Newport, Behr having successfully campaigned for it to be switched to Forest Hills, New York, a move that Williams opposed.

Having beaten Behr in the quarter-finals in 1914, Williams went on to take the title for the first time. He won it again two years later, played in five winning Davis Cup teams (he also captained the side), partnered Chuck Garland to the Wimbledon doubles title in 1920 and was a losing finalist in the Wimbledon doubles of 1924, the year he won the Olympic mixed doubles title.

Given the extraordinary life stories of the two men, however, it was perhaps understandable that they largely left it to others to record their sporting feats. "My grandfather never discussed his accomplishments on the tennis court and he never talked too much about individual matches, unless there was something amusing that happened during them," Griffin said. "He was modest and he was not given over to exceptional emotional analysis or display. I think he accepted life very much for the good and the bad."

Titanic survivor to lose title... after 88 years

Dick Williams' 88-year reign as Olympic mixed doubles champion will end this summer. The Titanic survivor won the title at the 1924 Paris Olympics playing with Hazel Wightman (who established the now defunct Wightman Cup women's team event).

The mixed doubles was not included when tennis returned to the Olympics in 1988, but will be staged again for the first time at this summer's tournament at Wimbledon.

Williams and Wightman beat their fellow Americans Vincent Richards and Marion Jessup 6-2, 6-3 in the 1924 final after Wightman declined Williams' suggestion that they withdraw after he sprained his ankle in the semi-finals.

Paul Newman

'Starboard at Midnight' by Helen Behr Sanford is published by Gazelle Books & 'Titanic: the tennis story' by Lindsay Gibbs is published by New Chapter Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments