Novak Djokovic: Tennis star’s diet revealed after influencing decision over Covid vaccine

The Serb maintains he has ‘always been a great student of wellness, wellbeing, health, nutrition’ and that his decision over the Covid vaccine has been partly influenced by the positive impact of changing his diet and his sleeping patterns

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Novak Djokovic maintains he has “always been a great student of wellness, wellbeing, health, nutrition” after reiterating his stance over refusing to be vaccinated for Covid-19.

The Serbian admits he could change his mind in the future after being deported from Australia after a row surrounding an exemption for the Covid vaccine.

But the 34-year-old’s decision has been partly influenced by previous lifestyle changes surrounding his diet and sleeping patterns, meaning he is ready to miss more Grand Slams this year in order to remain loyal to his principles.

It was a life-changing moment. Djokovic was in Croatia in the summer of 2010 for a Davis Cup tie and was having a consultation with Dr Igor Cetojevic, a nutritionist and fellow Serb.

Cetojevic told Djokovic to stretch out his right arm while placing his left hand on his stomach. The doctor then pushed down on Djokovic’s right arm and told him to resist the pressure. The strength Djokovic would feel in holding firm, the doctor said, was exactly what he should experience.

Next Cetojevic gave Djokovic a slice of bread. He told the bemused player not to eat it but to hold it against his stomach with his left hand while he again pushed down on his outstretched right arm. To Djokovic’s astonishment, the arm felt appreciably weaker.

It was what Cetojevic had expected. His crude test had been to discover whether Djokovic was sensitive to gluten, a protein found in wheat and other bread grains. Looking back, it was the moment when Djokovic discovered why he had suffered so many mid-match collapses in his career – and the starting point for a lifestyle change which led to his becoming world No 1 just 12 months later.

Until now Djokovic has been reluctant to go into detail about the regime that has turned his life and career around. Today, however, the 34-year-old Serb tells his story in a remarkable book, Serve To Win, which reveals how changing his diet has transformed his health and tennis.

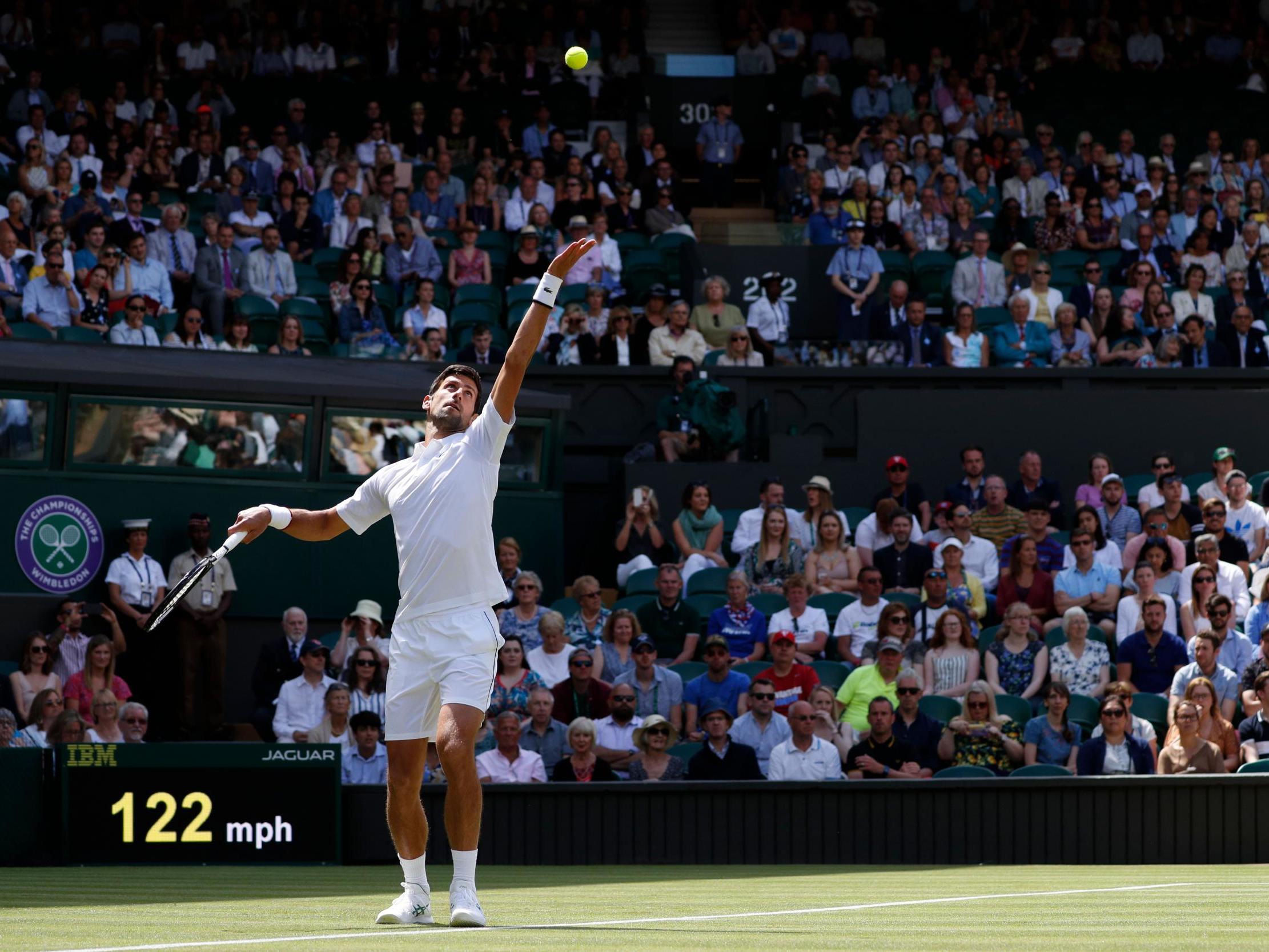

From being a player with suspect fitness, Djokovic has become arguably the greatest athlete in world tennis, combining stamina and strength with extraordinary speed and flexibility. He became world No 1 in 2011.

Djokovic’s connection with Cetojevic goes back to the 2010 Australian Open. The doctor, who had no interest in tennis, was at his home in Cyprus, flicking through the television channels, when his wife suggested they watch Djokovic’s quarter-final against Jo-Wilfried Tsonga. Djokovic was two sets to one up against the Frenchman when he suffered another of the physical crises that had bedevilled his career. He had trouble breathing and vomited violently during a toilet break. His strength sapped, he won only four games in the last two sets as Tsonga coasted to victory.

The watching Cetojevic immediately suspected what was wrong. He guessed that Djokovic’s breathing difficulties were the consequence of an imbalance in his digestive system which was triggering an accumulation of toxins in his intestines.

Cetojevic and Djokovic’s father had mutual friends and six months later the doctor was doing the bread test that confirmed his original suspicion. Cetojevic told Djokovic that he suspected food sensitivities were causing his physical problems and affecting his mental state. He told the player he could help him devise a diet that would be right for his body and could transform his health and fitness.

Subsequent blood tests showed that Djokovic was strongly intolerant to wheat and dairy products and mildly sensitive to tomatoes. Being told to stop eating bread and cheese and cut down on tomatoes was not the best news for someone whose parents owned a pizza restaurant, but the open-minded Djokovic was willing to give it a go.

Bread and pasta are staple foods in Serbia, but Cetojevic asked Djokovic to try a new gluten-free diet for two weeks. The effect was immediate. Djokovic felt lighter and more energetic and slept better than he had ever done. When Cetojevic suggested after a week that he should eat a bagel, the negative impact was startling. Djokovic felt sluggish and dizzy, as if he had a hangover.

When he switched permanently to the diet, the benefits quickly followed. Within 12 months Djokovic was 11lb lighter and feeling stronger and healthier. Ever since following the regime, he has felt fresher, more alert, more energetic and mentally sharper.

Djokovic’s early years as a professional were very different. In 2005 he had taken the first set against Guillermo Coria at the French Open but retired in the third because “my legs had turned to rock and I couldn’t breathe”. During a victory over Gaël Monfils at the US Open three months later he took four medical timeouts after running out of breath.

Djokovic had always worked hard on his fitness and in the search for a solution to his problems – which some put down to asthma – he changed trainers, adopted new training regimes, had nasal surgery and took up meditation and yoga. Although his physical condition improved – he claimed his first Grand Slam title at the 2008 Australian Open – the mid-match collapses did not go away.

When he moved his pre-season training camp to Abu Dhabi at the end of 2009, hoping to acclimatise to heat before heading to Australia, Djokovic thought he might have found the missing piece in the jigsaw, only for the meltdown against Tsonga in Melbourne to revive all his concerns. Thankfully for the Serb, however, Cetojevic was watching.

The key to the diet Djokovic now follows is the absence of both gluten – which is present in most foods – and dairy products. He also cuts out as much sugar as possible. The world No 1’s diet is based on vegetables, beans, white meat, fish, fruit, nuts, seeds, chickpeas, lentils and healthy oils.

He is meticulous about when and how he eats. Djokovic buys organic food wherever possible and cooks almost every meal himself; when on tour he always tries to stay in hotels which will let him use their kitchen. After saying a short prayer before meals – not to any specific god but to remind himself never to take food for granted – Djokovic eats slowly and deliberately. He never watches television or uses his phone or computer while eating.

His dedication to his diet is extraordinary. After winning his near six-hour final against Rafael Nadal at the 2012 Australian Open, Djokovic had a craving for chocolate, which he had not eaten for 18 months. His physiotherapist brought him a bar. Djokovic broke off one small square and let it melt in his mouth – but left the rest.

Serve To Win contains passages about Djokovic’s tennis career and his upbringing in war-torn Serbia, but for the most part it is a fascinating insight into his lifestyle. It contains recipes developed by Candice Kumai, a chef and author, and also goes into fine detail about the player’s daily life, including his fitness and training regimes.

Djokovic believes the diet has made him more level-headed and less anxious or prone to anger, though other routines have also helped in that respect. He never skimps on sleep and always tries to go to bed at the same time, between 11pm and midnight, before getting up at 7am. He uses yoga and meditation and believes in “positive thinking”.

The Serb’s training routine away from competition rarely changes. After 20 minutes of yoga or tai chi, followed by breakfast, he hits with a training partner for an hour and a half, does stretching and has a sports massage. After lunch – when he avoids sugar, protein and unsuitable carbohydrates – Djokovic does a one-hour workout using weights or resistance bands, after which he takes a protein drink. Another 90-minute hitting session, followed by stretching and perhaps another massage, concludes his day’s physical work.

If it seems extraordinary that a change of diet could so change an athlete’s life, Djokovic’s example has been followed by plenty of others. Several other tennis players have gone on to similar regimes and many tournaments now offer gluten-free and dairy-free food.

Dr William Davis, whose 19-year-old daughter Lauren is the world No 70, has written a foreword to Djokovic’s book. A cardiologist, Dr Davis has written extensively about the problems caused by eating modern wheat, which he says is the product of “genetic manipulations by geneticists and agribusiness”.

Among the physical problems Dr Davis says eating wheat can cause are ulcerative colitis, acid reflux, abdominal stress and rheumatoid arthritis. He also says it can contribute to paranoia, schizophrenia and autism. He says that eating wheat “has the potential to cripple performance, cloud mental focus, and bring a champion to his knees”. Djokovic knows exactly what he means.

‘Serve To Win’ by Novak Djokovic, is published by Bantam Press (£12.99)

Fit for a star: The champion’s menu

Day One

Breakfast Water first thing out of bed; two tablespoons of honey; muesli (including organic gluten-free rolled oats, cranberries, raisins, pumpkin or sunflower seeds and almonds)

Mid-morning snack (if needed): Gluten-free bread or crackers with avocado and tuna

Lunch Mixed-greens salad, gluten-free pasta primavera (including rice pasta, summer squash, courgettes, asparagus, sun-dried tomatoes and optional vegan cheese)

Mid-afternoon snack Apple with cashew butter; melon

Dinner Kale caesar salad (kale, fennel, quinoa and pine nuts) plus dressing (including anchovies or sardines); minestrone soup; salmon fillets (skin on) with roasted tomatoes and marinade

Day Two

Breakfast Water first thing out of bed; two tablespoons of honey; banana with cashew butter; fruit

Mid-morning snack (if needed): Gluten-free toast with almond butter and honey

Lunch Mixed-greens salad, spicy soba noodle salad (including gluten-free soba noodles, red bell pepper, rocket, cashews and basil leaves, plus spicy vinaigrette)

Mid-afternoon snack Fruit and nut bar; fruit

Dinner Tuna nicoise salad (green beans, cannellini beans, rocket, tuna, red pepper, tomatoes and canned chickpeas), tomato soup, roasted tomatoes

Day three

Breakfast Water first thing out of bed; two tablespoons of honey; gluten-free oats with cashew butter and bananas; fruit

Mid-morning snack (if needed): Home-made hummus (including chickpeas and gluten-free soy sauce) with apples/crudités

Lunch Mixed-greens salad, gluten-free pasta with power pesto (including rice pasta, walnuts and basil leaves)

Mid-afternoon snack Avocado with gluten-free crackers; fruit

Dinner Fresh mixed-greens salad with avocado and home-made dressing; carrot and ginger soup; whole lemon-roasted chicken

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments