Next Gen Finals prove popular with players and punters alike as tennis tries to win over new generation of fans

The Association of Tennis Professionals, which runs the men’s tour, is determined to make that tennis will continue to appeal to the next generation of fans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Daniil Medvedev looked despairingly at the umpire. His opponent, Borna Coric, had just hit a thumping backhand past him which landed perilously close to the line. With no “out” call, Medvedev, perhaps hoping for an over-rule, looked in vain towards Gianluca Moscarella, who responded with a gentle shrug of the shoulders.

In the brave new world of this week’s NextGen ATP Finals here, the umpire’s role can amount to little more than keeping the score.

Having every line called by Hawk-Eye’s all-seeing cameras rather than by line judges is one of several innovations being trialled at the inaugural NextGen Finals, which have brought together the year’s most successful players aged 21 and under. The Association of Tennis Professionals, which runs the men’s tour, wants to make sure that tennis will continue to appeal to the next generation of fans.

For the most part the experiments have been welcomed by players, officials and spectators, even if the event got off to the worst possible start with its poorly judged draw ceremony, which was widely criticised for being sexist as the eight players chose female models to reveal their round-robin groupings.

Matches are played over the best of five sets, with each set won by the first to four games and a tie-break played at 3-3. There is only one deuce in any game, after which a deciding point is played.

There are no “lets” on serve – if the ball hits the top of the net and lands inside the service box play continues – and an on-court shot clock enforces the 25-second rule between points. Warm-ups are restricted to five minutes and spectators can walk in and out at any time, rather than have to wait for a change of ends. Players can communicate with their coaches via a head set – with their conversation broadcast on television – between sets.

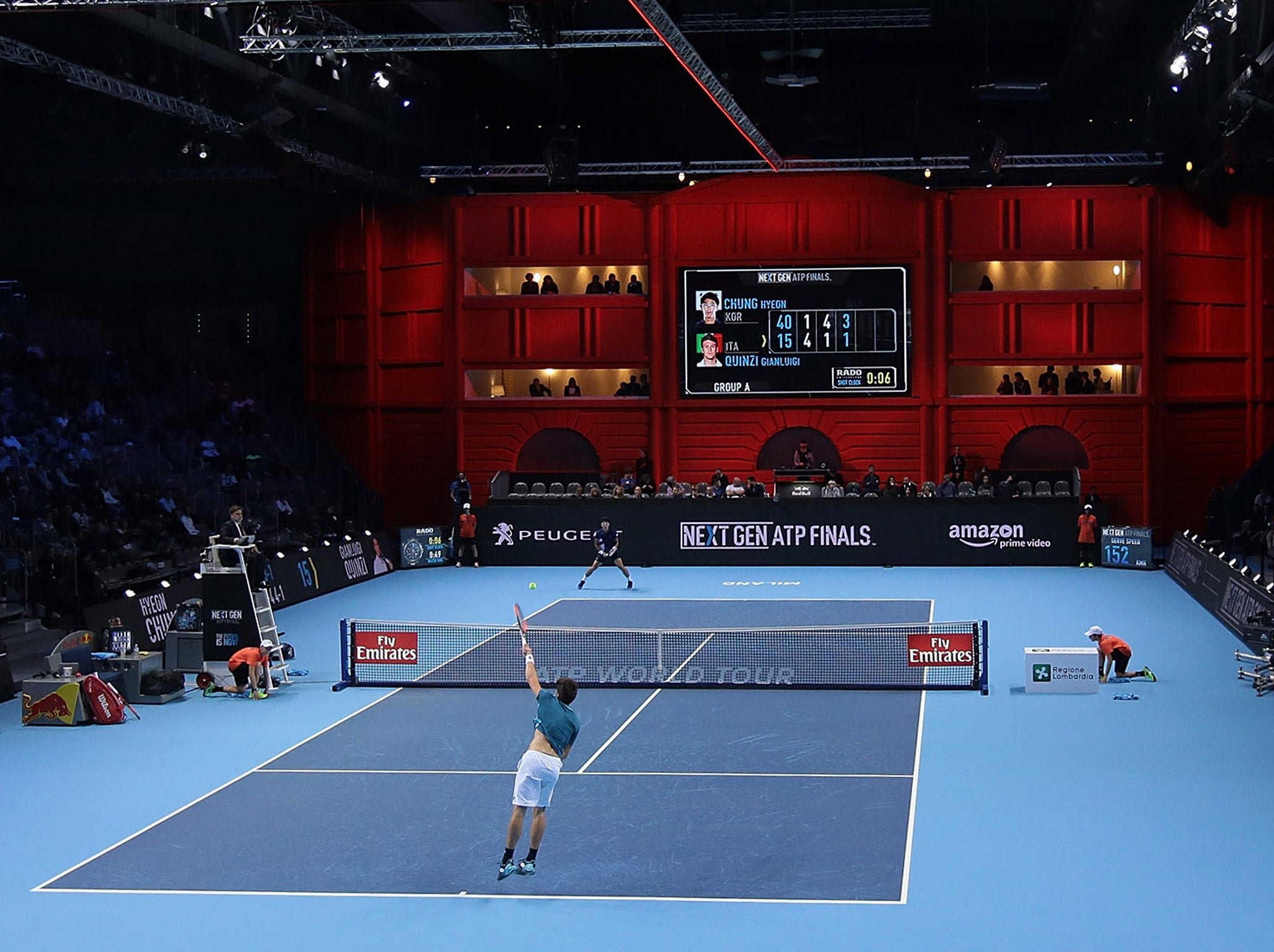

The differences are striking as soon as you enter the 4,500 temporary arena at the Fiera Milano exhibition centre. There are no conventional “tram lines” on the court, which is marked only for singles play. Combined with the absence of line judges, this helps to focus attention more than ever on the two players. During the changeovers, nevertheless, eyes might be diverted to the end where a disc jockey is playing music in front of a striking red recreation of Milan’s La Scala opera house.

A recorded voice calls “out” whenever Hawk-Eye intervenes, so there are no challenges, though particularly close calls are replayed on the big screen. The system cuts out all errors, but spectators may regret losing the tension when a shot is replayed on the screen after a challenge, while the rule allowing three incorrect challenges per set can provide additional drama as a player weighs up whether or not to go to Hawk-Eye.

The big screen here is also used to display graphics showing shot placement, which Medvedev thought could be useful when trying to predict where an opponent will serve. “I looked at mine and I had to change something,” he said.

While the disembodied voice calling “out” can be rather jarring, the players like the extended use of Hawk-Eye, even if Russia’s Karen Khachanov would prefer to hear a different voice. “I think it’s better that all umpires record their voices and each match they are on, it’s the voice of the umpire in the chair,” he said.

Khachanov also thinks the sets are too short and that the deciding point at deuce gives too much of an advantage to the receiver. Medvedev, however, says the new format simply forces players to focus throughout. “You need to be good from the start to the end of the set,” he said. “You cannot have one moment where you relax your concentration.”

A major reason for the experiments has been a feeling that matches can be too long and that there are too many “dead” periods, particularly early in sets. Here the format inevitably means that there are more “important” points. Most of the matches have been played eyeballs-out from the start.

Matches can be shorter, but most have lasted more than 90 minutes and Hyeon Chung’s victory on Thursday over Gianluca Quinzi was the first to pass the two-hour mark.

Denis Shapovalov agreed that tennis needs to provide “more action” for spectators. “Sometimes you have to watch matches for five hours and three-out-of-five sets [as played at the Grand Slam events] is long,” he said. “It’s also physical on the body [for the players]. It’s not easy. To make it shorter and more intense would, I guess, raise viewers.”

Players generally like the shot clock and have no objection to the coaching via headphones, but are not so sure about the “no-let” rule. The crowds have been sizeable and supportive and most of the players seem unconcerned by the additional noise and movement in the stands.

This is billed as “tennis re-imagined”, but Chris Kermode, the ATP’s executive chairman and president, insists the event is not about “messing with the rules”. He said he would be happy even if none of the experimental changes were eventually adopted.

“At least we’ll have had a look and tried things,” he said. “I think what most sports do is wait too long and assume that the show, the products that they have, will last for ever in the same format. For the next five years we could probably not change anything, but what I’m looking at most importantly is the next generation of fans.”

He added: “It’s not just about reducing time, because if a product is boring for six hours then it can be boring for six minutes. It’s part of the issue – about what the time should be for tennis – but it’s more about taking away the dead time and making more points matter quicker. I think that’s what has shown here. We’ll see over the rest of the week what works, but the intensity so far has certainly been quite extraordinary.”

Kermode believes the men’s game, in the era of Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic, Andy Murray and Stan Wawrinka, has never been in better shape but added: “While the game is in such good health in terms of on-site attendance, TV numbers and commercial revenues, let’s look down the line, from a position of strength, at what we should be looking at in the future.”

The next generation of players are clearly right behind him. “I think sport needs to advance and change,” Shapovalov said. “It's definitely cool to have a tournament where we can try these new rules out.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments