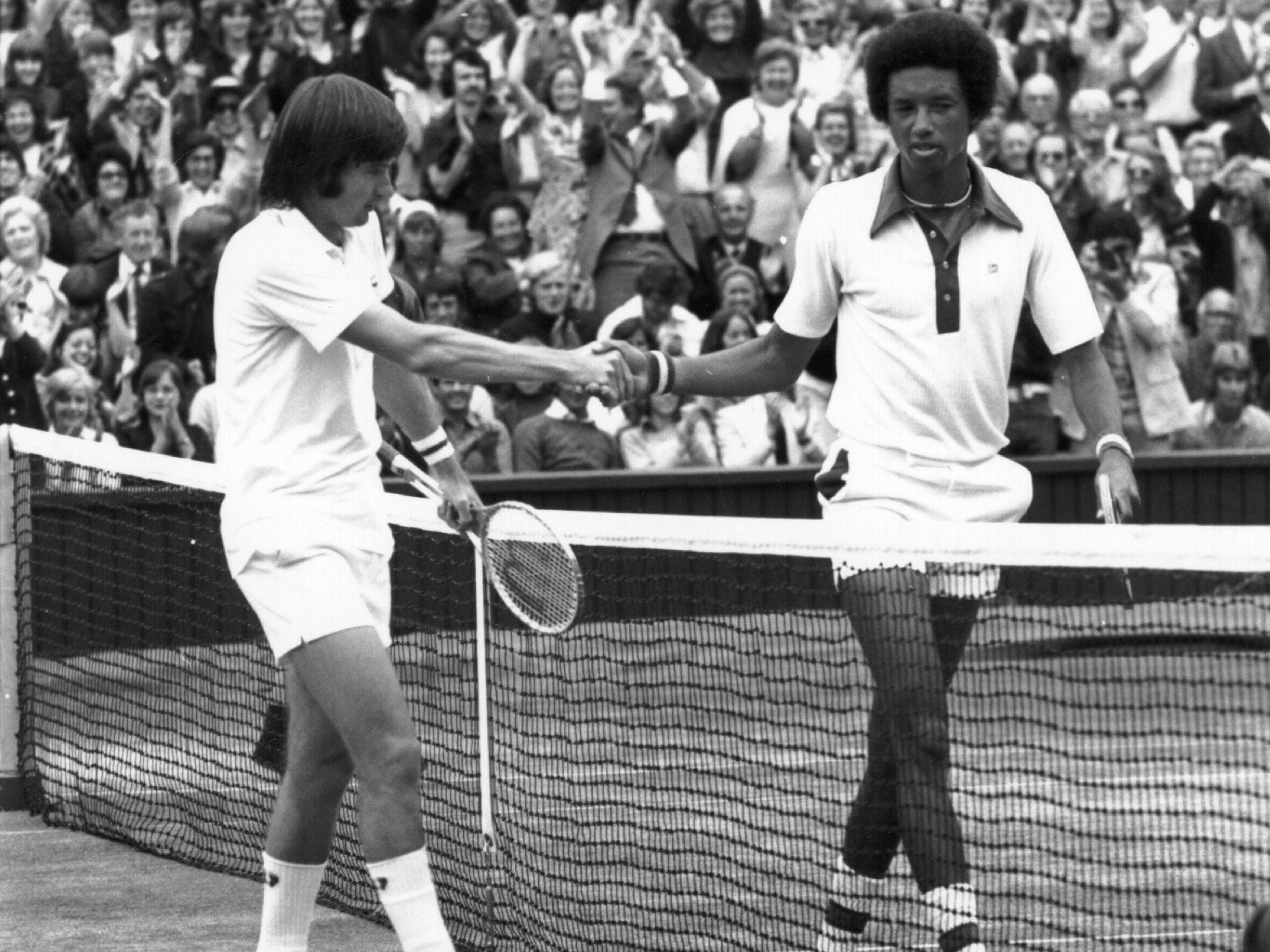

Arthur Ashe vs Jimmy Connors: The attraction of opposites

Forty years on, the 1975 Wimbledon men’s final remains an iconic showdown: young v old, brat v gentleman, black v white. Paul Newman retells one of the most compelling stories in the history of tennis

There have been greater Wimbledon finals, many of them less one-sided and with appreciably more twists and turns, but for those who witnessed it there has surely never been a more extraordinary and bewitching encounter than the 1975 showdown between Arthur Ashe and Jimmy Connors. Forty years on, their final remains a lesson in how sporting encounters can be won in the head just as much as on the field of play.

Ashe’s brilliant tactical triumph over the outstanding player of the day would have been memorable just for the tennis that was played, but it was so much more than that. It was a victory for age over youth (at 22, Connors was nine years younger than Ashe) and a day when one of the great gentlemen of tennis finally got the better of one of its most outspoken brats.

The underdog’s 6-1 6-1 5-7 6-4 win was also seen as a victory for Ashe’s patriotism over Connors’ pursuit of wealth, while on a political level it was viewed as a triumph for those seeking to build a unified structure that could benefit everyone in the new world of professional tennis over an individual who relished standing alone from the rest.

All of that was without the obvious matter of race. Ashe, the first black player ever to represent the United States in the Davis Cup, remains to this day the only black man to have won Wimbledon.

For all the differences between the two men, nevertheless, there were similarities in their life stories, as the respected American journalist Peter Bodo describes in an illuminating new book. While neither came from affluent backgrounds, their families were not poor. Both grew up under the strong influence of a single parent: Ashe’s mother died when he was six, while Connors’ mother, Gloria, dominated his early life.

Ashe was brought up in Richmond, Virginia. He was a sickly child but had an aptitude for sport, with skills particularly suited to tennis, although it was not a popular sport within the black community. From an early age he was taught to behave properly on court. His father told him never to throw his racket while one of his early coaches told him that he should always call “in” any shot hit by an opponent that landed near a line, even if it fell two inches beyond it.

As a teenager, Ashe moved to St Louis, where he could practise with some of the country’s top juniors on lightning-quick wooden courts and developed the serve-and-volley game that would stand him in good stead in later years. Having initially been a baseliner, Ashe developed into an attacking player who loved to go for audacious shots.

There were also life lessons at that time. When Ashe went with some of his white friends to a cinema they were turned away because of his colour. The group decided to play pool instead. Having graduated from the all-black Sumner High School in St Louis, Ashe went to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) before joining the US Army. He spent most of his army time at the military academy at West Point as a “data processor”.

Connors, meanwhile, was born in East St Louis, not far from where Ashe completed his school education. His autobiography, published last year, is entitled The Outsider. Connors always considered himself and his family to be outsiders, looking in on the cosy world of tennis. He was coached by his formidable mother and his grandmother Bertha Thompson.

As a boy, Connors was not strong. When he first picked up a racket he needed two hands and would hit the ball double-handed from both sides. He would eventually take his right hand off the racket to hit his forehands, but would remain two-handed on the backhand flank. There were players before him who had hit double-handed backhands, but Connors was the man who set the modern-day trend. At home he practised on a rough concrete court squeezed tightly into the backyard. It taught him to take the ball especially early, which was to be one of his great strengths.

Connors was an angry young man but his mother knew how to channel his rage. She told Sports Illustrated: “We taught him to be a tiger. ‘Get those tiger juices flowing!’ I would call out, and I told him to try to knock the ball down my throat, and he learned to do this because he found out that if I had the chance, I would knock it down his. Yes, sir. And then I would say, ‘You see, Jimbo, you see what even your own mother will do to you on a tennis court’?”

Approaching his 16th birthday, Connors moved to Los Angeles, where he was taken under the wing of Pancho Segura, a former player. Segura came up with the final piece in the jigsaw by getting Connors to rally from the baseline rather than from two feet behind it. It meant that he could take time away from opponents more effectively than ever. Connors quickly emerged as a player of huge and fearless talent.

Ashe, in his memoir Days of Grace, which was published just after his death in 1993, gave a perfect description of Connors’ game and character. “If Connors was sometimes ill-mannered, brusque, and downright truculent, he seemed to have the approval of his mother, Gloria Connors, and her own mother,” Ashe wrote. “The women had obviously wanted to shape a fighter and they succeeded brilliantly.

“Physically unprepossessing, even a little frail, Connors nevertheless wore an air of such arrogance that he regularly intimidated his opponents even before he had hit a ball. Then he proceeded to smack the ball with a force that bordered on vindictiveness. His two-handed backhand shot from mid-court, when he had time to play it well, was among the most damaging strokes ever seen in tennis.”

Connors’ on-court behaviour was often outrageous. He would scream obscenities and regularly clutch his groin or suggestively caress the handle of his racket. If opponents dared to hit winners or question line calls, he would wag his finger at them.

Although their paths had crossed occasionally in Los Angeles, Connors had little to do with Ashe until they started meeting on the tennis court. Nevertheless there had been an embarrassing episode at a tournament in Louisville, Kentucky in 1970, when Ashe played doubles with Ilie Nastase, who became one of Connors’ best friends. Connors helped Nastase put black make-up all over his face before he walked out on court. Ashe, fortunately, saw the funny side, though Connors later admitted in his autobiography: “We weren’t all that bright back then, to say the least.”

Ashe won the first of his three Grand Slam titles at the 1968 US Open – he was the first African American to win the title – and his second at the 1970 Australian Open. By the early 1970s he was as much known for his work as a leader within the sport – he was one of the founders of the Association of Tennis Professionals, who today run the men’s tour – and for his increasing involvement in wider political issues, particularly race.

Connors was the only leading player not to back the ATP, which led to many clashes between Donald Dell, Ashe’s manager, and Bill Riordan, a hard-drinking, chain-smoking and combative man who ran Connors’ affairs. Riordan, who founded the Independent Players’ Association in opposition to other professional circuits, was frequently involved in lawsuits with his rivals. Nearly all the top players boycotted Wimbledon in 1973 in protest at the banning of Niki Pilic, a founding member of the ATP. Connors was one of the few leading men who played.

In 1974, Connors’ involvement in another commercial enterprise, World Team Tennis, probably cost him the prize of becoming the only man other than Don Budge and Rod Laver to win a pure Grand Slam of all four major tournaments in the same year. Connors won Wimbledon and the Australian and US Opens that year but was banned from the French because of his involvement in WTT, as a consequence of which Riordan fired off another round of lawsuits.

Before they contested the 1975 Wimbledon final, Connors had beaten Ashe in all three of their meetings. The tensions between the two men had been heightened earlier in the year. While the United States were losing to Mexico in a Davis Cup tie, the country’s best player, Connors, was in Las Vegas, where he won $100,000 by beating Rod Laver in a much-hyped exhibition match.

Ashe, a future Davis Cup captain, said that Connors was “seemingly unpatriotic” in repeatedly refusing to play for the United States. Connors filed a libel suit, demanding millions in damages, which he dropped only after losing the Wimbledon final.

And so to the All England Club, where Connors, the top seed, injured his knee in his first-round victory over Britain’s John Lloyd. After the semi-finals he was advised that he could do himself long-term damage by playing in the final. Connors dismissed the idea but told Riordan not to pass the medical report on to his mother. According to Connors, Riordan subsequently made a trip to a bookmaker and placed a huge bet on Ashe to win the final.

Connors had also been hauled up before the Wimbledon committee, who had been upset by his criticism of the state of the grass. According to his autobiography, Connors told them: “This is bullshit and we all know what’s going on here. Instead of worrying about the tennis, all you care about is what the press is saying about your precious grass.

“How about paying less attention to what I do off the court and more to what I do on it. Give me a break. And while you’re at it, why don’t you bring that bowler hat back to East St Louis and see how you get treated?”

On the eve of the final Ashe discussed tactics over dinner with Dell, his manager, and Charlie Pasarell, a fellow player and friend. Pasarell recalled a match he had watched Connors lose in 1971 in Los Angeles. The 19-year-old had been sweeping aside everyone in his path, but had been outwitted by the 43-year-old Pancho Gonzalez, who baffled him with an array of delicate and carefully placed strokes, including drop shots and lobs.

Ashe’s natural game was to attack and go for his shots, but the strategy the three men devised for him was to take the pace off the ball, focus mostly on Connors’ forehand, where he could be particularly vulnerable on low volleys, and use the lob. At only 5ft 10in, Connors might have trouble with lobs, particularly on his backhand side with his double-handed grip. Just before Ashe went on court, Dell gave him a hand-written note: “Keep the ball low, and mostly on Connors’ forehand side; serve him wide to the backhand; use the lob.”

From the moment the two men walked on to the grass the scene was set for an unforgettable afternoon. Ashe entered Centre Court wearing his Davis Cup tracksuit, with USA emblazoned across it. Connors was wearing a Sergio Tacchini top in the Italian national colours.

From the start Ashe returned serve beautifully, gave his opponent little opportunity to fire up his groundstrokes and repeatedly lobbed him after drawing him into the net. Connors had been blasting opponents off the court with the power of his Wilson T-2000 steel racket, but had few opportunities to do so here. Ashe, meanwhile, benefited from the greater control of his fibreglass and aluminium Head racket.

With Connors serving on break point in the third game, Ashe hit a sliced backhand to Connors’ forehand before putting up a beautifully judged lob, which the younger man smashed beyond the baseline. Two games later another lob gave Ashe a second break.

In the second set Ashe continued to attack Connors’ forehand wing. With Ashe leading 3-0 a spectator called out: “Come on, Connors!” He screamed back: “I’m trying, for Chrissakes, I’m trying!”

After losing the second set, Connors at last launched a fightback. Although he repeatedly struggled to hold serve, the top seed fought ferociously and broke Ashe in the 12th game to take the set.

Connors went 3-0 up in the fourth, but Ashe remained calm, believing that the Connors storm would soon blow over. Having fought back to 4-4, he sensed that now was the time to attack, and he surprised Connors with a series of big shots.

At 15-40 Connors was barely able to pick up a stunning backhand return and was already heading back to his chair by the time Ashe put away his winner.

Using his sliced serve to great effect as he had all match, Ashe won his final service game with something to spare.

For Richard Evans, doyen among British tennis writers (and the first tennis correspondent of this newspaper), it remains one of Wimbledon’s greatest triumphs. “Intellectually and strategically it was the most amazing match I have ever seen,” he recalled this week. “Walking out on court for the biggest match of your career and playing in a way that was totally contrary to your natural style was an amazing sporting feat. It was like watching a fast bowler go out and bowl leg spin.”

Ashe greeted victory with a raised arm and clenched fist. “Some will mistake this gesture for the controversial Black Power salute, but this is not a win for Black Power, or any other kind of power,” Bodo writes. “This is a win for the tennis player Arthur Ashe.”

1975 and beyond

Wimbledon in 1975 was Arthur Ashe’s last appearance in a Grand Slam final. Four years later he suffered two heart attacks and was forced to retire. In 1988 he was diagnosed as HIV positive. It was believed that he had contracted HIV through a blood transfusion during heart surgery five years earlier. He died of Aids-related pneumonia in 1993.

In his final book, Days of Grace, Ashe wrote: “Quite often, people who mean well inquire of me whether I ever ask myself, in the face of my diseases, ‘Why me?’ I never do. If I ask, ‘Why me?’ as I am assaulted by heart disease and Aids I must ask, ‘Why me?’ about my blessings, and question my right to enjoy them. The morning after I won Wimbledon in 1975 I should have asked, ‘Why me’?”

Jimmy Connors, who finished runner-up in all three Grand Slam tournaments he played in 1975, went on to enjoy a record-breaking career. His 109 titles, the last of which he won at the age of 37, is a record on the men’s tour. He was runner-up on 54 occasions and played in more tournaments (401) and won more matches (1,337) than any other man in the Open era.

He won eight Grand Slam titles: five US Opens, two Wimbledons and one Australian Open.

Ashe vs Connors, by Peter Bodo, is published by Aurum Press, £16.99

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies