Andrea Jaeger: The dark truth behind a tennis star’s burnout

A two-time grand slam finalist while still a teenager, Jaeger is often cited as one of tennis’s early examples of burnout. She tells Tom Kershaw how sexual harassment and subsequent threats drove her away

For almost 40 years, Andrea Jaeger has found it easier to conceal her trauma than to keep reliving it, let alone become a poster child for abuse or be seen as “a victim or broken”. She has never viewed herself like that, not when she was a teenage prodigy taking tennis by storm, nor as an adult who has dedicated her life to giving children a sense of the joy that was stolen from her. To do that would be to let those who betrayed their authority win, and what propelled Jaeger to fame was a fierce hatred of losing.

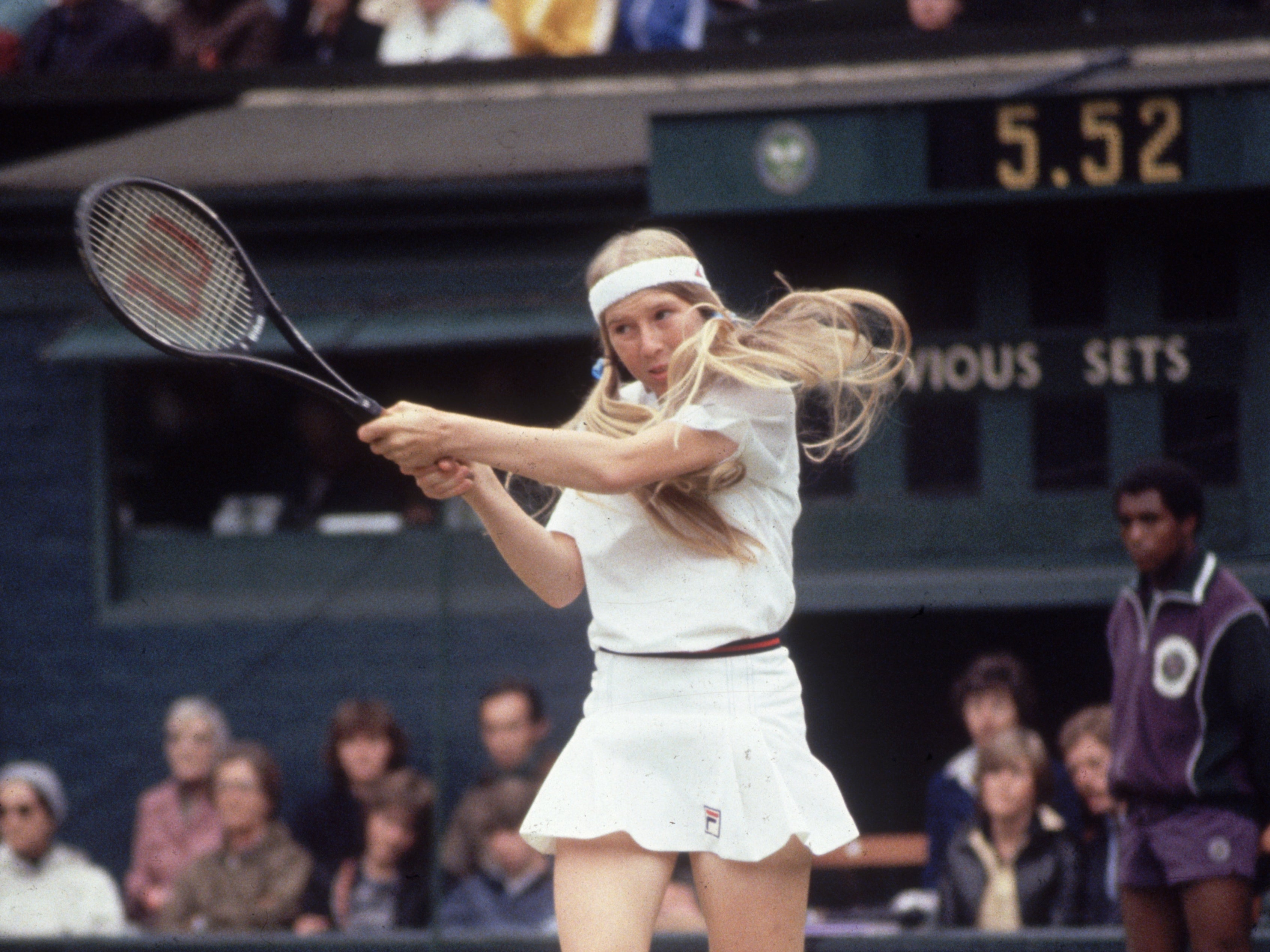

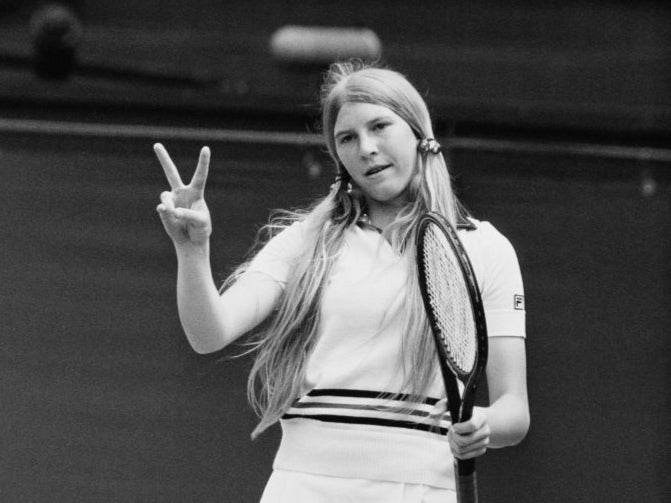

The record books show that she reached five grand slam semi-finals and a Wimbledon final before she turned 18 and was ranked as high as No 2 in the world. Jaeger beat the likes of Billie Jean King, Martina Navratilova, Chris Evert and Tracy Austin, earned millions as the popularity of women’s tennis exploded in the 1980s, and was a household name across the world before she learned how to drive to the end of her road.

But her legacy now is that of a rising star who burnt out prematurely, for whom early success became the catalyst for injury and uneven temperament. That remained Jaeger’s story because she wasn’t yet ready to discuss the WTA staff member who persistently sexually harassed her in the locker room, eventually forcing Jaeger to take refuge in portable toilets at major tournaments. Nor was she prepared to describe the time she was unknowingly served alcohol while still underage before a different staff member drove her home and attempted to kiss her on her doorstep. But there is a part of Jaeger that has always wanted to set the record straight, so people would understand the difference between burning out and having the light drained from something you love.

“My story was that she couldn’t handle the pressure... I could play in a tornado and still win a match,” she says, shifting back sharply to the same combativeness of old. “I never had a problem with pressure. I had a problem trying to keep myself safe and sane at the same time.”

***

The biggest match of Jaeger’s career was her Wimbledon final in 1983 but the result was initially cast into history as an anticlimax. Navratilova took the first set to love and closed out victory inside an hour. It was only 15 years later when Jaeger claimed she’d lost on purpose that it took on a different kind of relevance. She explained that on the eve of the match, she had bolted out of her apartment after an argument with her father, Roland, and knocked on Navratilova’s door. She threw the final because she feared people might think she’d deliberately attempted to disrupt her opponent’s preparation.

In follow-up interviews, Jaeger offered white lies to reporters such as the row stemming from being forced to practise with an injured thumb or that her father had flown into a rage after catching her eating a packet of crisps. The truth, she says now, is that Roland had been approached by two concerned mothers of other players about the safeguarding of teenagers on the WTA Tour. Scared he’d left his daughter in harm’s way, Roland sat Andrea down and demanded she tell him everything. “If I had told him the truth, he’d have pulled me from the final and taken matters into his own hands,” she says. “I didn’t want to be the one to affect tennis’s catapult rise and stop something that was good overall just because certain people couldn’t control their behaviour.”

Jaeger decided to protect Roland and the sport she loved. She never told him what happened, even after she retired in 1985 due to a shoulder injury, because she didn’t want him to feel responsible. Besides, the problems had begun in the women’s locker room, which was the one place he wasn’t able to shadow her every step.

Jaeger was only 14 years old when she turned professional and was thrust into an adult environment. Her sudden success coupled with a fiery attitude soon made her a target. “I had situations where I’d go to get my racket and the strings would be cut,” she says. “When I went to put on my shoes, someone had left razor blades inside them.” Then, there were the comments from other players as she got changed. One insisted on making jokes about the size of Jaeger’s breasts and how they were “developed” for her age, and frequently drew them to the attention of other players. “My constant thought was, who is the kid here, me or them? It was so gross. It was disgusting, really.”

The abuse made Jaeger uncomfortable but she considered those incidents “normal harassing”. They were the consequence of being in such a cutthroat environment, and she didn’t want to be seen as weak or be ostracised by calling things out. It was the culture of silence, though, that enabled certain individuals whose intentions were not just improper but outright sinister.

Jaeger refers to one female WTA staff member in particular who “had a major problem keeping her hands to herself”. She estimates the person, who she does not want to name and no longer works at the organisation, made physically inappropriate advances on her in the locker room on at least 30 separate occasions “very, very early in my career”. When a senior player saw one of the incidents, they called it “crazy” but “did nothing to stop it”. Not long afterwards, Jaeger stopped using the physio room if other players weren’t present because of “another approach” made there.

“I’d change in portable toilets or a bathroom stall because I didn’t want to deal with the comments, interest or actions of people,” she says. “Someone recognised me at the US Open once and asked what I was doing, so I just said a pipe was broken in the locker room. There was always the concern I may have to deal with an adult who had problems with being either verbally or physically inappropriate with me.”

Even when she wasn’t the direct target, Jaeger says a lack of protection became a constant source of anxiety. That Pam Shriver was in a relationship at 17 with her 50-year-old married coach, Don Candy, was common knowledge and far from a unique scenario. “There was a physical therapist who was in a relationship with one of the players,” Jaeger says. “I had a groin injury, a muscle strain, and should have got it examined but I didn’t want to get treated by that person. All these unethical situations are something that a 14- to-19-year-old should never be dealing with.”

There were times when Jaeger wanted to tell her father about what was happening, but she was more worried about what his reaction might be. Roland was an amateur boxer in his youth who still refused to pull his punches and was infamous on the circuit for his hardline approach and hostile temper. He never suspected anything because “parents don’t assume a successful organisation could have these sorts of people, and when kids are put in those situations, normally they don’t say things and I didn’t”.

But in 1982, there was a tipping point that pushed Jaeger to make a complaint. After losing to Evert in the final of the WTA Championships in Florida, she had to attend a players’ party that evening hosted by one of the tournament’s sponsors, a well-known brand of rum. When a WTA staff member asked her if she’d like a drink, Jaeger ordered the non-alcoholic cola Tab. “She came back with two glasses,” she says. “I thought mine tasted really weird.”

After her third glass, Jaeger began feeling “fuzzy”. She went over to the bar, pointed at the WTA staff member and asked the bartender what they’d ordered. They insisted all three Tabs had rum. It was the first time Jaeger had ever drunk alcohol. When the party was ending, the WTA employee gave Jaeger a lift back to her apartment. “I went with her and her girlfriend in the car,” she says. “The person was swaying driving and I remember we hit either some garbage or a mailbox. When we got to my condo, she walked me to the door and tried something on with me. She was trying to kiss me. I was so sickened that I was crawling up the stairs inside trying not to throw up so my dad wouldn’t see me.”

Jaeger was 16 years old. It wasn’t just the breach of trust that left Jaeger nauseated, it was what happened after she confided in someone in authority at the WTA. “I said this has got to stop. Every week I have to worry about this s***,” she says. “They said if you say one more word about this, we’ll make sure your sister’s scholarship at Stanford gets pulled. Every time I tried to stand up for myself, I was threatened with someone else getting harmed.

“Do you know how hard it is to tell an adult in an industry that there’s a problem, how much courage that took? My parents were owed the right that if you put a kid on the court late at night or you’re going to have a WTA Tour representative drive them home, they’re going to be safe. They were owed that right and never got that right.”

Jaeger still had to face the same staff member at tournaments. The revulsion she felt eventually transformed into being physically sick. “It wasn’t anxiety that caused me to throw up, it was my disgust,” she says. When a doctor recommended Jaeger have her tonsils removed, she remembers feeling a wave of relief washing over her. “I was in the hospital having surgery, and I felt safe,” she says, and so as her form and fitness wavered, she began to create more injuries as a means of escape. “For whatever reason, God gave me a gift of joy and faith, that I can survive through anything, and I found joy in other things.”

***

Most of us spend our lives running away from grief but the “hell” of life on the circuit turned hospitals into Jaeger’s sanctuary. In between tournaments, she began meeting and dropping off gifts to children who were living with terminal illnesses or suffering from serious conditions. It can be hard to understand why someone would submerge themselves in that cycle of suffering, let alone a teenager, but Jaeger felt like she could relate to the sense of losing a childhood. “What happens is the moment physical abuse occurs, emotionally a child’s life is lost,” she says.

She never sought to publicise her charity work but, when Jaeger visited a school in New York that had experienced cluster suicides, one of the parents sent some photographs to a newspaper. The following day, Jaeger says she was called into a meeting at a hotel with a WTA executive. “She threw the newspaper at me and said you have to quit doing this, you’re making us look bad. We won’t allow it anymore.” Jaeger says her protests fell on deaf ears for reasons she’s never managed to understand. Given an ultimatum to choose between her career and helping good causes, she took the shoulder injury she suffered two months later at the 1984 French Open as a sign from above.

Jaeger was described as a “lost soul” and a “loose cannon” when she announced her retirement. Roland found her decision impossible to understand or accept and their relationship became increasingly strained. But while Jaeger still loved tennis itself, her heart had long left a circuit that made her feel unsafe and then unwelcome. In the following months, she took up hospital positions and studied courses on how to handle children who’d been in abusive situations. She sold her car, then her jewellery and watches, to make charitable donations before setting up her own foundation, at first running activity programmes for children with cancer. Now in its 37th year, the Little Star Foundation offers long-term care to ill and neglected children across the US. People used to think she was mad to give her multimillion-pound fortune away, but perhaps now it’s easier to understand why.

The scar tissue stays under the skin forever, some days more prominently than on others. When Jaeger played a Wimbledon legends event in 2019, she still didn’t want to use the locker rooms. Once, at the US Open, she left her friends at the gate because she couldn’t face going inside. You would not have guessed it, though, because of how she has refused to let it define her. Jaeger is relentlessly kind, effusive and impassioned, but she hopes that by speaking about what happened, she might help at least one child who is being let down by those supposed to protect them.

“I can see how in any sport, even now 40 years later, if a kid was confronted with similar situations they may also stay quiet when threatened,” she says. “I don’t want to enable any further harm to happen.” Because if that is the real story behind the teenage phenom who burnt out, her legacy is the hundreds of young lives she’s brought a light to since.

Click here to learn more about Andrea Jaeger’s Little Star Foundation