The story of Althea Gibson: the first African-American to win the US Open and how she changed the game forever

Flushing Meadows will celebrate the 60th anniversary of Gibson's landmark victory on Friday - but it is the late tennis player's achievements off the court which really secured her legend

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The US Open is in full swing, but if you walk down most streets in the Flatbush neighbourhood of Brooklyn, barely 12 miles across the city from Flushing Meadows, you would never guess that the world’s best tennis players are in town. Basketball is probably the game of choice in this ethnically diverse part of New York, though you get the impression that professional sport does not figure high on a list of priorities for most locals here.

It comes as a surprise, therefore, to find a large tennis mural on a wall around the back of the Brooklyn Beer and Soda store in Franklin Avenue. The identity of the three players pictured tells you much about what it takes for tennis to make an impact outside its often privileged bubble. The painting is not of Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal or even Garbine Muguruza, the next women’s world No 1, but of three black players: Serena Williams, her sister Venus and Althea Gibson.

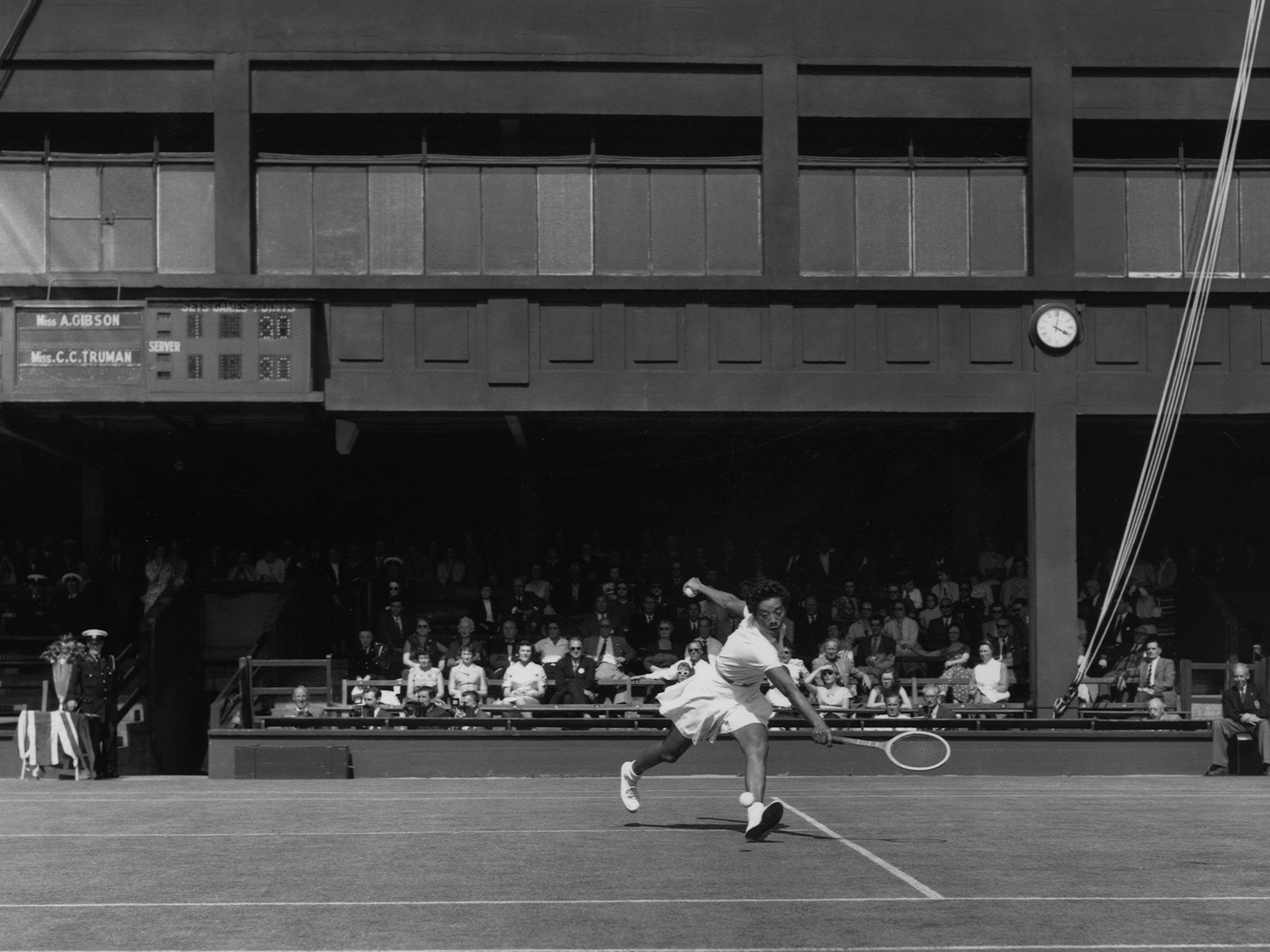

While the Williams sisters have done so much to generate interest in tennis away from its traditional bases, they would be the first to acknowledge the debt the sport owes to Gibson, which will be recognised here on Friday as the tournament celebrates the 60th anniversary of one of its landmark moments. It was on 8 September 1957 that Gibson became the first African-American to win a title at Flushing Meadows, though in many respects it was her victories off the court that were of greater significance than her triumphs on it, which included two US and two Wimbledon titles.

Until she was 23 Gibson was not even allowed to compete against white opponents, but her successful challenge to the United States Lawn Tennis Association’s bar on black players paved the way for men and women of her colour, including Arthur Ashe, MaliVai Washington, Zina Garrison and the Williams sisters.

Katrina Adams, a former player who two years ago became the first African-American Chief Executive Officer and President of the United States Tennis Association, said: “Althea is the player who really broke the colour barrier. When she played at the US Lawn Tennis Association Championships that was a first. What she did, to go on and win it two times, and to win Wimbledon twice, really opened the door and broke the barrier for people of her colour to say: ‘Hey, I too can do this if I have an opportunity.’

“If it wasn’t for Althea and what she did I wouldn’t be in the position that I am today and wouldn’t have had the career that I’ve had, because who knows how much longer it would have been for the next player to come along? She was such a great athlete – charismatic and really strong in nature, not just physically but mentally, to be able to withstand the barriers that were there for her.”

Gibson’s family moved to New York from South Carolina during the Depression in the hope of a better life. They lived in Harlem, where the young Althea played truant, got drunk on an uncle’s illicit whisky and rode the subway late at night to escape her father’s beatings.

Athletic and sporty, Gibson was given two second-hand tennis rackets when she was 13. She learned to play at the Cosmopolitan Tennis Club in Harlem and won her first American Tennis Association national title in 1947. The ATA organised competitions for black players, who were barred from competing in the United States Lawn Tennis Association’s tournaments.

However, opposition to the colour bar grew, with Alice Marble, a former Wimbledon and US champion, among those who campaigned for change. “If tennis is a game for ladies and gentlemen it’s time we acted a little more like gentlepeople and less like sanctimonious hypocrites,” she wrote in a magazine article.

At last, in 1950, Gibson made a successful application to play in the US Nationals at Forest Hills, which was the forerunner to the US Open. However, it was another six years before she won her first Grand Slam singles title, in Paris, at the age of 28. In 1957 she became the first black player to win a singles title at Wimbledon, after which she was given a ticker-tape parade on her return to New York. She had turned 30 by the time she beat Louise Brough to win the US title two months later.

Gibson retained her Wimbledon and US titles the following summer, but turned professional in 1959, when she signed a contract to play during half-time intermissions at the Harlem Globetrotters’ basketball matches. She then turned to golf and became the first African-American to play on the Ladies Professional Golf Association tour.

In her later years, however, Gibson fell on hard times. Britain’s Angela Buxton, who won the women’s doubles title with her at Wimbledon in 1956 and became a firm friend, raised funds to help her former partner, who died in 2003 at the age of 76.

“Later in her life Althea became more of a recluse and didn’t really participate in a lot of the activities or the tennis tournaments,” Adams said. “I think the last one she may have attended was the Wimbledon final in 1990, when Zina Garrison played Martina Navratilova.

“I was probably 10 or 11 when I met Althea for the first time. She came to Chicago and did a clinic. As a child you didn’t really understand the magnitude of what she had accomplished. Not until later in life did I learn to appreciate who she was and what she did for people like me in the game.”

Today Adams is the executive director of the Harlem Junior Tennis and Education Program. “We focus on inner-city kids, providing them with tennis as a vehicle to earn a college scholarship,” Adams said. “We make sure that we continue to educate our youth on who Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe were.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments