Brian Ashton: Football can teach my code plenty of lessons

Tackling The Issues

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I've never subscribed to the theory of isolationism as a means of improvement: back in 2003, when I was in charge of the Rugby Football Union's national academy, one of my key principles was to mix with, and learn from, top-level performers and coaches from across the sporting spectrum.

The intention was to make the academy a thought-provoking place to be; somewhere that offered physical and mental stimulus by exposing people to unfamiliar environments and challenging them at a level from which they derived personal satisfaction. The single-sport approach – rugby, and only rugby – all too often produces the kind of narrow-mindedness that undermines progressive learning and reinforces the status quo.

You may have read earlier in the week, in this newspaper, an account of a meeting between myself, Neil Warnock, the Queen's Park Rangers manager, and Angus Fraser, the former England pace bowler who now runs cricket at Middlesex. It was a real privilege to engage in a wide-ranging discussion on various topics within England's three biggest sports and it gave me the opportunity to listen, learn and take away ideas I could adopt and adapt as a way of improving my own coaching.

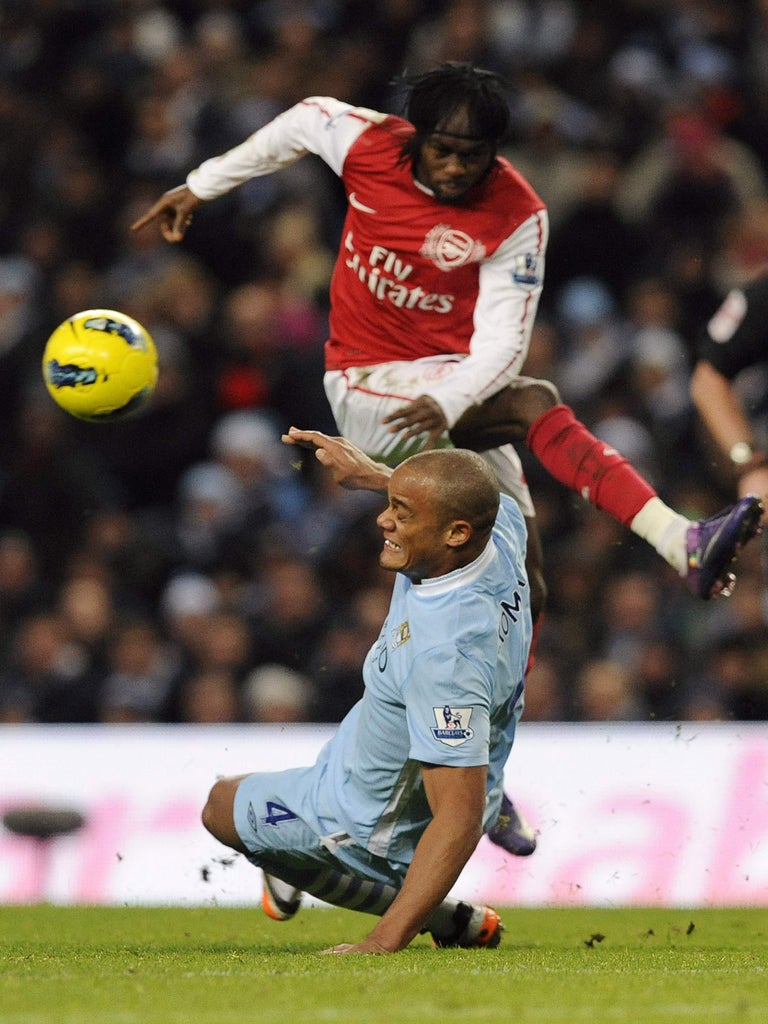

With all this circulating in my mind, I watched last weekend's Manchester City-Arsenal game as a guest of Kevin Roberts, chairman of USA Rugby, chief executive of Saatchi and Saatchi International, an old boy of Lancaster Royal Grammar School (like myself) and a vociferous City supporter. If you ever find yourself in need of some emotional and intellectual stimulation, 10 minutes in Kevin's company will sort you out nicely.

Having marvelled at many aspects of the contest, I left the ground telling myself that I should spend more time watching live Premier League football. From first whistle to last there was no mistaking the attacking intent of both sides, and it made for riveting viewing. As I tend to do on these occasions, I jotted down during the course of the game elements of play that I later checked against my own coaching ideas and values. I might just point out at this stage that, while there have been many positive influences on my development over the years, the most influential coaching book I ever read was the Football Association Guide to Teaching and Coaching, written by Allen Wade in 1966. While the physical conditioning and technical side of the sport were covered in detail, the main thrust of Wade's book concerned the principles of play with and without the ball that enables a team to function successfully.

So what did I learn at the Etihad Stadium? In no particular order; 1) The control and accuracy of the players under intense and ever-changing pressure was immensely impressive – skills underpinned by intelligent movement from virtually everyone on the field when they were not in possession. The general willingness to seek out space and offer options was outstanding; 2) The pace at which all this took place is only truly discernible when watching live. Television does not come close to highlighting this quality; 3) The vision and communication skills common to the vast majority of the players ensured there was little in the way of hit-and-hope football: the long ball was sparingly used, and only when appropriate; 4) The way both sides dealt with transition play – the turnover, in rugby parlance – was highly instructive. Their capacity to be both reactive and proactive with their own and the opposition's changes of shape amounted to a coaching lesson.

It set me thinking that much of the best of football is transferable to the union game, provided the coaching mindset allows for it and the players are willing to meet the challenge. It means stretching the imagination beyond the traditional collision/contact mentality and showing a desire to discover exactly what might be achieved by using the 7,000 square metre area of the rugby field to its fullest extent. It seems to me that Harlequins have been moving down this road more quickly than anyone in England. If they have been persistent underachievers in the professional age, they are making something of themselves now. Conor O'Shea, the director of rugby, is steering the ship on a course that both challenges and excites the players, who appear to be working in a thoroughly positive and enjoyable environment.

This was evident last week, when they registered a remarkable Heineken Cup victory at Toulouse. The two sides had met in London eight days previously, when Quins were blown off the park. In particular, they were bullied at the tackle area. To their credit, they addressed this problem and came up with a solution: certainly, there were no backward steps the second time around. To a significant extent, their competitiveness in this area denied Toulouse the opportunity of playing their characteristic free-flowing game, with all its subtle variety. It also allowed Quins to play challenging, dynamic rugby of their own and record a famous triumph.

Even more impressive in some ways was the characteristic modesty of Conor in a midweek interview. He was unequivocal in arguing that he had simply built on good structures already in place and insisted that the real plaudits should go to the players. He did not seek at any point to take credit, and while it is obvious that he has had a lively influence on life at the Stoop, it was refreshing to encounter some genuine humility. Perhaps the most significant point made by the Irishman concerned his players' striving for "optimum performance" week in, week out, and his assertion that talk of winning was rarely, if ever, the No 1 item on the agenda. This topic – the balance between performance and result – often creates heated debates in top-level sporting environments.

For my part, I see it as a no-brainer. Below-par performance rarely results in victory and playing only to win can be a massive, pressurising distraction. When you play at your top performance level, or preferably increase it, you are likely to be a tough team to beat. More often than not, the outcome – surprise, surprise – will be a "W".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments