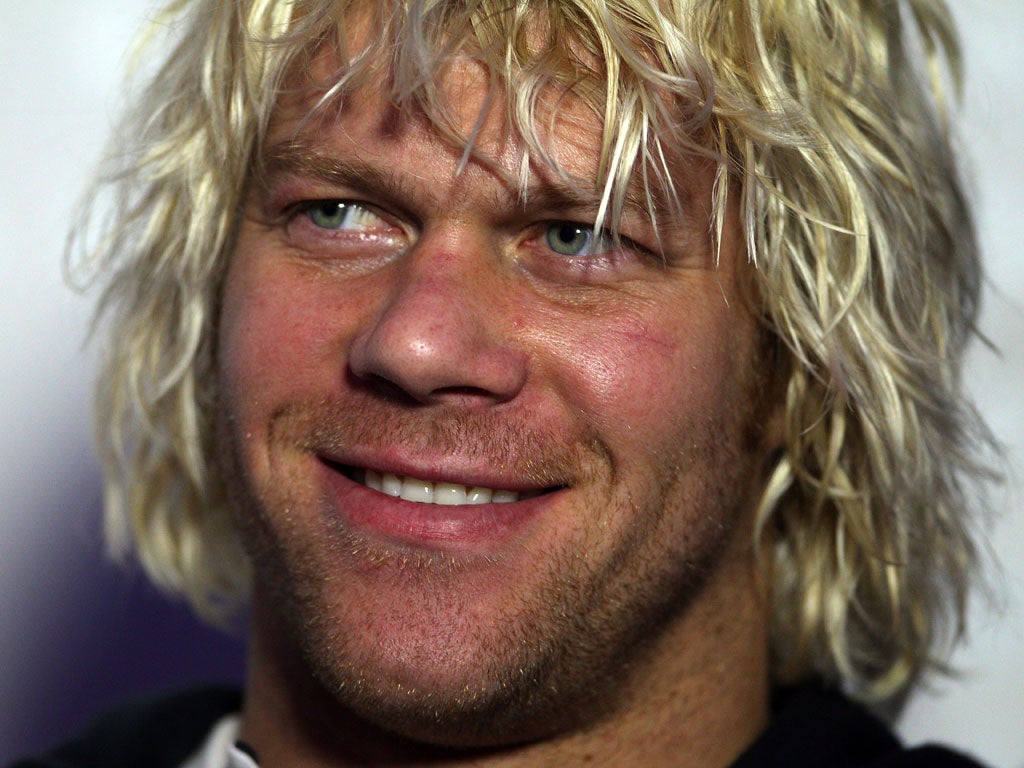

Mouritz Botha: Blond With Bottle

It's been a long road to the top for Mouritz Botha. Laid off from his office job, he begged for a chance with Sarries. Now all the hard work has paid off. He talks to Chris Hewett

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The average rugby romantic does not, as a general rule, turn to South African lock forwards when he goes in search of his spirit-soaring fix.

There was nothing alluring about Louis Moolman or Moaner van Heerden, an engine-room pairing from hell who reduced many a pack to its component parts during their time in the Springbok side, and if Johannes de Bruyn had a hearts-and-flowers side to him, it was not obvious to the late Gordon Brown of blessed Lions memory. Brown built an entire after-dinner routine around events in Pretoria in 1974, when he sent De Bruyn's glass eye flying from its socket and then watched, in a state of advanced petrification, as his opponent reinserted it, tufts of grass still attached, before heading back to the line-out for a continuation of the argument.

Even in the professional age, with its all-seeing cameras and citing officials, Bakkies Botha has managed to win himself a permanent place in the Springbok bestiary, and judging by the way the World Cup-winning hard man's namesake performed on his first international start last weekend, there is no obvious reason to think that South African second-rowers have suddenly discovered pacifism. Mouritz Botha may have been playing for England, but he performed like every ultra-ruthless Bokke lock who ever took the field in a green shirt.

Yet the story of this Botha – the red-rose Botha – is positively dripping in romance, of the kind modern rugby effectively disowned the moment it sanctioned pay-for-play in the mid-1990s. This Botha never saw the inside of an academy, or won age-group honours, or bought himself a flash car while still in his teens because he was flush with sporting lucre. Instead, this Botha knows what it is to be made redundant from an office job, to wash carpets and strip asbestos for a living and to play grass-roots rugby for Bedford Athletic, who are not even the best team in Bedford.

Now a success at Saracens – he was one of the central figures in their drive towards the Premiership title last season – and revelling in his new-found status as a Test forward, he can afford to view his trials and tribulations as part of the great scheme of things. The plan did not seem quite so grand when he was trying to make his sporting way in South Africa, though. There were moments when he was playing club rugby in Cape Town when he wondered whether he was wasting his time.

"My last team back home were NNK," he says, referring to Northern Northlink College, which, being a mouthful, benefits from the abbreviation. "What standard was it? Not great. The equivalent of National Division One rugby here – maybe Division Two. They gave us 250 rand if we won." That being the vague equivalent of £20, it did not quite propel him into "don't spend it all at once" territory. "It was just about enough for a night's beer," he says, emphasising the "just about" part of the sentence.

"I was 22 and going nowhere, so I got on the web and checked out some clubs in England, where I thought I might stand a better chance of making some sort of breakthrough. Bedford Athletic were good enough to show an interest and their director of rugby told me that if I played well, there was a bigger club across town who might take me on." That club was Bedford Blues, one of the stronger sides in the second-tier Championship. "Straight away, I trawled their website for information about the locks they had at the club: how tall they were, how much they weighed. I worked out how much I'd have to do physically to compare favourably with them."

Sure enough, the Blues offered him a contract, which was good news for everyone ("I realised I shouldn't have been playing in Midlands League One, where Bedford Athletic were at the time, because I was hurting people," Botha admitted last year, before winning a first England cap off the bench in a World Cup warm-up game with Wales. "I was in a comfort zone, which was not good from the health-and-safety point of view"). Better news was to come. "I had a message on Facebook from an agent, saying Saracens were on the hunt for a lock," he says. "Looking back, it was quite a moment."

Botha tells a wonderful tale about his meeting, at the Old Albanians ground on the leafy outskirts of St Albans, with three fellow South Africans at the heart of the Saracens operation: the former Springbok captain Morne du Plessis, who had a seat on the club board; Brendan Venter, the Bokke centre who succeeded Eddie Jones as director of rugby in 2009; and Edward Griffiths, the chief executive. On balance, however, it is Griffiths who tells the story best.

"Yes, I remember it vividly," says the CEO. "We had one place in our squad left to fill and we were looking specifically for a lock. Our primary target was a Fijian international but someone at the club had watched Mouritz playing somewhere or other and suggested we talk to him too. I was in the room with Morne and Brendan when the Fijian guy walked in. We asked him why he wanted to play for Saracens and he told us that as his wife was in the British Army and was stationed up the road, it would be really convenient for them both. Then it was Mouritz's turn, and his response was rather different.

"He told us that in all his years playing rugby in South Africa, no one had ever given him a break – that he'd never had the rub of the green. I could understand that. I knew he came from Calvinia, up in the Northern Cape, and it can be tough for people from that area to get into the right schools and get streamed in the right way. South Africa isn't exactly short of big, strong, athletic rugby players and if you don't get the kind of break Mouritz was talking about, you can easily fall through the net.

"Then, we heard Mouritz say something along the lines of: 'This is the most important day of my life, because if I don't get a break here, that's me done. I'll never play top-level rugby.' As he said it, his jaw went a little. I think we were all struck by the emotion of it. When he left the room, Morne said it was obvious to him that we should sign him on the basis of his desire alone – and Morne, with all that vast experience, has a feel for these things. As Mouritz opened the door of his car, I phoned his mobile and told him there was an offer of a year's contract on the table. We all watched from the window as he sat in the driver's seat and punched the air in celebration. Forty-five minutes later, he was still parked there, phoning family and friends."

In a way, Botha has been celebrating ever since. He may not be the greatest line-out forward ever to wear the red rose – his partner at Saracens, the former England captain Steve Borthwick, is in a different league altogether when it comes to this crucial theatre of action – but when it comes to the less structured, more dynamic areas of the contest, he is a Lord of Chaos who revels in the dark deeds of a second-row enforcer. Early in the piece at Murrayfield last weekend, he took a fearful smack on the head as he ventured into the Scottish 22 and stayed down for treatment. Did it worry him? Quite the opposite. "You get used to that sort of thing," he says, merrily. "It settles the nerves."

There were nerves aplenty in Edinburgh last weekend. "Amazing experience," he says. "The stadium just getting dark, the drums, the bagpipes, the atmosphere with 70,000 people singing 'Flower of Scotland' – that sort of thing makes the hair on the back of your neck stand up. It will be the same in Rome this weekend. Italy have made strides – they're not an automatic wooden-spoon team any more – and they'll have a huge crowd behind them. We face a big battle. There again, I like a battle.

"Did I always believe deep down that I could play Test rugby? I think I did. But that's not the thing, is it? The thing is convincing other people you can play Test rugby. I've convinced them well enough to be where I am now and I cherish it. And when I sit down and analyse it, I believe I bring a different perspective to the game because I've followed an unusual route to get here. I don't envy the players who have come up through the academies. Not really. I've had to work hard for this, but at least I've had a taste of outside life. The people running the academies should make more of an effort preparing players for the world outside rugby. We'll all be in that world sooner or later."

Perhaps the last word should go to Griffiths – the man who made that phone call. "The point with Mouritz," he says, "is that he doesn't take the pampered lifestyle of the professional sportsman for granted. He appreciates what he has: he's a guy who says 'thanks'. And we should be thanking him, in a sense, because he's proved to everyone in rugby that there is more than one way of reaching the top."

Italian jobs: Great escapes against Azzurri

Huddersfield 1998

England no longer play World Cup qualifiers. The last time they had to, Clive Woodward's side found molto trouble against Diego Dominguez, Alessandro Troncon and Massimo Giovanelli, who was not disposed to take prisoners. The Azzurri had two perfectly good tries disallowed, yet the hosts still needed a last-minute Will Greenwood try to win 23-15.

Rome 2008

At 14 points up at half-time via early tries from Paul Sackey and Toby Flood, there was no obvious reason to think that Brian Ashton's side would have many problems. But David Bortolussi chipped away with the boot, Simon Picone crossed on 76 minutes and England held on to win 23-19 thanks to their captain, Steve Borthwick, who single-handedly ransacked the Azzurri line-out at the last knockings.

Rome 2010

Horrible. England fell into a trough of negativity after a bright start and had it not been for Mathew Tait's try just after the break, they would have been in a sea of strife. Mirco Bergamasco's goal-kicking put Italy within two points as the clock ticked down and it was left to Jonny Wilkinson to drop a goal at the death for a 17-12 win.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments