Great Olympic Friendships: Shuhei Nishida and Sueo Oe, the friends who wouldn’t be divided by their medals

The pair's medals, formed by fusing their honours together, became known as 'The Medals of Friendship'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

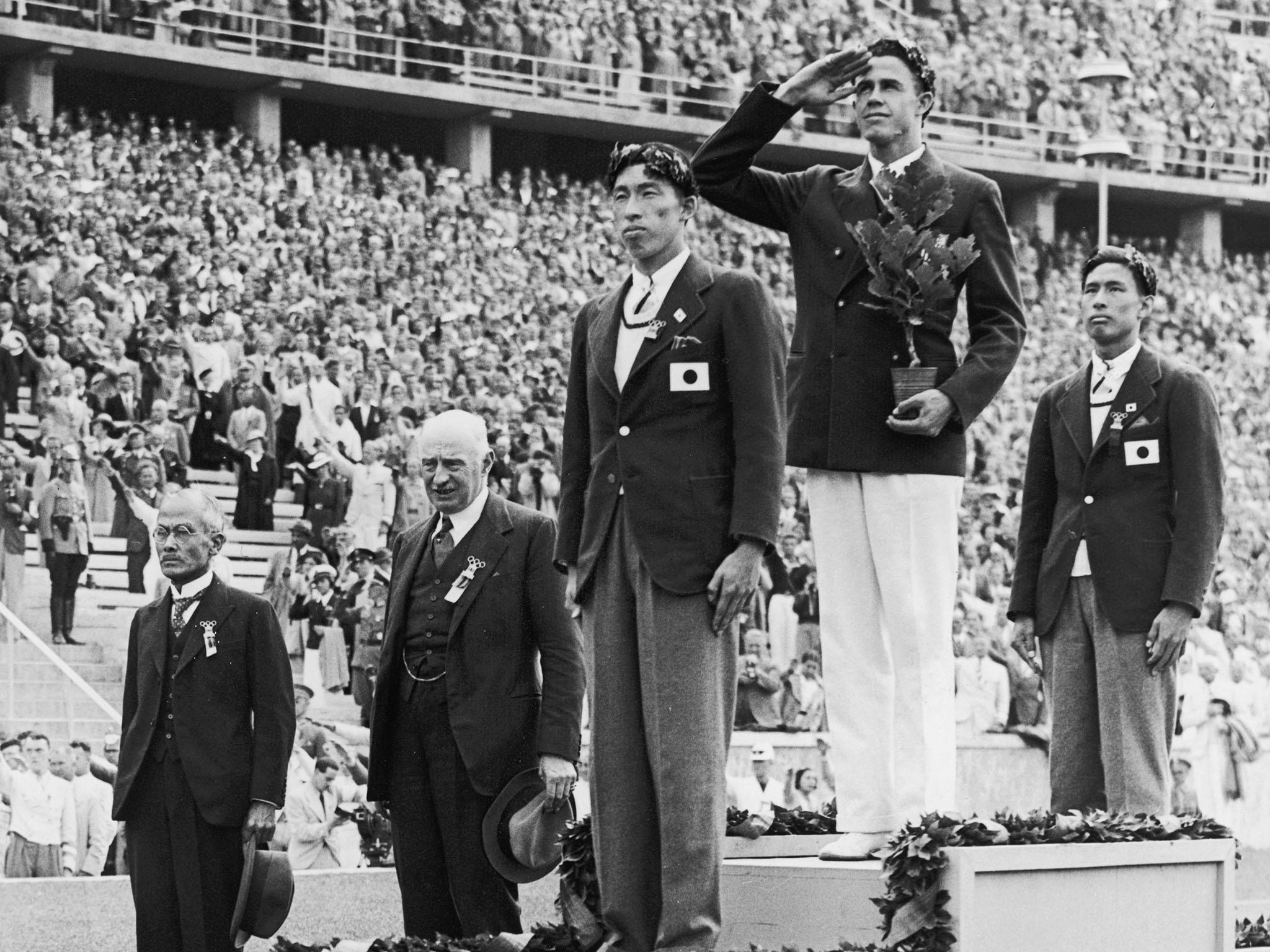

Your support makes all the difference.Five athletes reached the final stage of the men’s pole vault at the 1936 Olympics, having cleared the then impressive height of 4m 15cm. At the climactic jump-off, with 25,000 spectators braving the chill of the Berlin evening, it eventually grew so dark that night-lighting had to be switched on. You can still see parts of it in Leni Riefenstahl’s film, Olympia.

Bill Graber, of the US, was first to drop out, after failing to clear 4.25. Then Earle Meadows, another American, cleared 4.35 – a mighty vault in those days, which the remaining three, one American and two Japanese, all attempted without success. Meadows went on to try 4.45, but failed. But the main part of the competition was settled. Meadows took gold – leaving the other three to take part in a jump-off to determine who should take silver and bronze.

Bill Sefton, the American, failed to clear the bar on the first trial. The two Japanese competitors succeeded, meaning each was assured of a medal. But who would get which?

Both young men were students, Shuhei Nishida at Waseda university and Sueo Oe at Keio. More importantly, both were friends. And so – to general astonishment – they refused to compete further. They wanted to share the honours.

Their request was rejected. Someone had to take bronze and someone silver. The Japanese team was told to make its own decision about who should claim second place and who third. After lengthy discussion, it was agreed that Nishida, who had vaulted 4.25 at his first attempt, should take precedence over Oe, who had needed two attempts at that height.

The medals were awarded on that basis. But the athletes remained dissatisfied. Returning to Japan, they decided to take matters into their own hands. They had both medals cut in half and then fused into two hybrid medals, each half-silver and half-bronze (although the “bronze” was actually copper). The medals became known as “The Medals of Friendship”.

Oe died in 1941, in the war; Nishida died in 1997. Oe’s medal remains in private hands but Nishida’s is kept by Waseda university. In each case, the peculiar half-and-half medals serve as permanent reminders that, even in the hate-filled atmosphere of Hitler’s Germany, the Olympic Games allowed young people to display something more lasting, and ultimately more thrilling, than mere athletic excellence.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments