Rio 2016: A beacon of brotherly love at the Nazi games

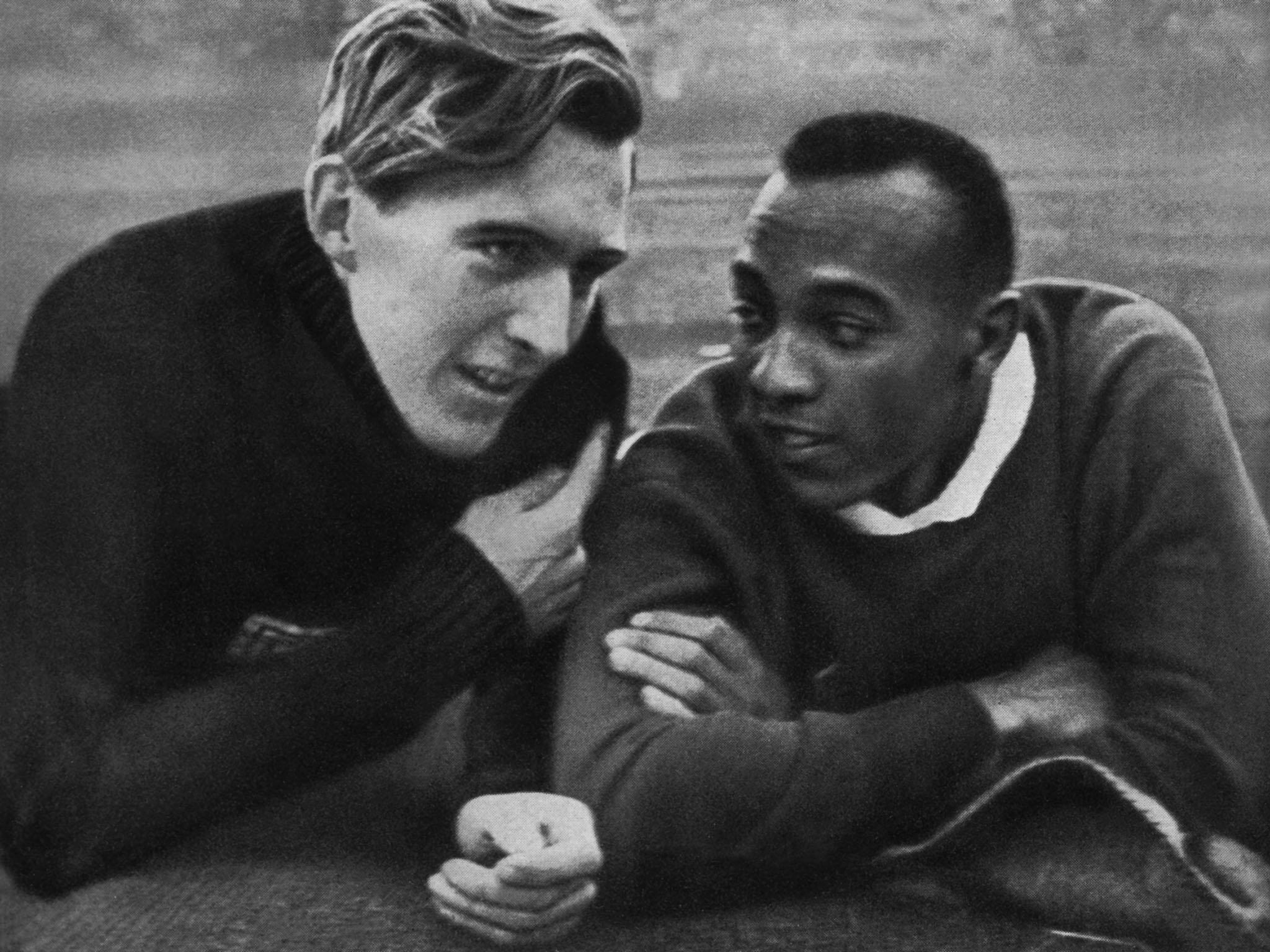

Luz Long and Jesse Owens

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Jesse Owens collected his fourth gold medal of the 1936 Olympics as a member of the United States 4x100m relay team – his 12th event, including heats, in the space of seven days – he completed a unique sequence of achievement that still stands as an incomparable indicator of sporting excellence. The 22-year-old son of Alabama sharecroppers and grandson of slaves, Owens was competing in the most intimidating environment imaginable. The scene of his triumphs was Berlin, where the racist ideology of the Nazi regime was building towards its full, awful intensity - and where the great instigator himself, Adolf Hitler, was a regular spectator in the stands of the Olympic stadium.

Nazi propaganda was already portraying negroes as “black auxiliaries”. And, as Albert Speer, Germany's war armaments minister, recalled in his memoirs, Inside The Third Reich, Hitler was “highly annoyed” by Owens's series of victories. Speer added: “People whose antecedents came from the jungle were primitive, Hitler said with a shrug; their physiques were stronger than those of civilised whites and hence should be excluded from future Games.”

To maintain a peak of achievement over a whole week in such an ugly moral environment was a mark of Owens's courage and determination.

He won the 100m and 200m with relative ease, despite some high-class opposition. The margins of his victories did not diminish their sporting and cultural significance. His final track gold – he helped set a sprint relay world record that would stand for 20 years – was slightly marred by a selection controversy which was a reminder of the ugly themes that were never wholly absent from the background of the Berlin Games. Two Jewish athletes, Sam Stoller and Marty Glickman, were dropped from the US relay team on the morning of the first heats, and Glickman for one was convinced that the US Olympic Committee president, Avery Brundage, had adjusted the team in order to avoid exacerbating the Führer's sensibilities. It was one unedifying episode which diminished the lustre of Owens's final Olympic flourish. Yet part of the glory of his Olympic achievement was the fact that, as relentlessly as the racists of various nations tried to poison the proceedings with their messages of hate, his own personal story continued to demonstrate the other side of the Olympic ideal: not the jingoistic one, but the ideal of sport as a force that can bring the human family together. Which brings us, belatedly, to Owens's second medal.

On 4 August, the day before his 200m victory, Owens had already received something he subsequently claimed he prized above anything that found its way round his neck during those seven days of glory: the comradeship of “Luz” Long.

At first glance, the German long jumper - tall, blue-eyed and blond - was the personification of the Aryan ideal of Nazi ideology. And although Owens arrived for long jump qualifying on the morning of 4 August as world record holder, he was soon put on his guard by the sight of Long taking prodigious leaps in practice. On the face of it, here was an ideal opportunity for the Nazis to see their theories of racial supremacy put into practice.

The qualifying distance was 7.15m, hardly a stretch for the man who had jumped 8.13m. But, having won his early morning 200m qualifying round in an Olympic record of 21.1sec, Owens failed to see the judges raising their flags to indicate the start of competition. Still in his tracksuit, he took a practice run down the approach and into the pit, only to see officials indicating that this had counted as the first of his three efforts.

Discomfited, he fouled on his next attempt. This left him with only one remaining jump to ensure that he reached the final later in the day.

At this point, according to Owens, the embodiment of the Aryan ideal sauntered up to him and introduced himself in English. David Wallechinsky, in his standard work, The Complete Book of the Olympics, reports the subsequent conversation thus. “Glad to meet you,” said Owens tentatively. “How are you?” “I'm fine,” replied Long. “The question is, how are you?”

“What do you mean?” asked Owen.

“Something must be eating you,” said Long, proud to display his knowledge of American slang. “You should be able to qualify with your eyes closed.”

Then, apparently, Long suggested that, as the qualifying distance was only 7.15m, Owens should shift his mark back to ensure that he took off well short of the board and remained clear of any possibility of fouling again.

Owens complied, retracting the initial marker for his run-up by a foot and a half before taking off uninhibitedly to qualify with just half a centimetre to spare.

When the final was held later that afternoon, Owens took a first round lead with 7.74m. In the second round, generating a deep roar of approval within the Olympic stadium, Long matched that mark, only for the American to respond with 7.87m. But on his fifth and penultimate attempt, the German created general uproar, and jubilation in an official tribune that contained not just Hitler but Goebbels, Goering, Hess and Himmler, by matching Owens again.

As Owens prepared to respond, it was his German opponent who raised both arms in the air as if to still the ferment, casting what Parienté described as a “furtive” glance towards his nation's unruly rulers.

Now Owens embraced his opportunity, fluent on the runway, his feet pattering lightly before a take-off that re-established his superiority as he landed at 7.94m. With his sixth and final attempt, Long could not improve on his best. Hitler immediately rose and left the stadium - missing the American's concluding effort: 8.06m.

“That business with Hitler didn't bother me,” Owens later wrote. “I didn't go there to shake hands. What I remember most was the friendship I struck up with Luz Long. He was my strongest rival, yet it was he who advised me to adjust my run-up in the qualifying round and thereby helped me to win.

Recent scholarship has suggested that Owens may, over the years, have exaggerated the significance of Long’s intervention in the long jump. Yet there can be no doubt about the warmth of the two men’s friendship. “We corresponded regularly until Hitler invaded Poland,” wrote Owens, “and then the letters stopped. I learnt later that Luz was killed in the war, but afterwards I started corresponding with his son and in this way our friendship was preserved.”

Long perished in a British military hospital after receiving fatal wounds during the Battle of St Pietro in 1943. Owens, who took up smoking after his athletics career ended, died of lung cancer on 31 March 1980.

Owens's haul of medals was eventually matched, in scope at least, by Carl Lewis, in the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. What gives Owens's achievement a far deeper resonance is the context: he gave the lie to Nazi ideology in its very cradle, under the gaze of its creator.

Owens's long jump victory is well documented in Olympia, the film made by German director Leni Riefenstahl, which was intended to offer enduring proof of Aryan superiority. Meanwhile, as a symbol of hope - of sport as a celebration of our common humanity - his relationship within that event with the man who finished as silver medallist could hardly be bettered.

The tall, doomed German was the first to congratulate Owens in his moment of victory.

“You can melt down all the medals and cups I have,” Owens wrote later. “And they wouldn't be a plating on the 24-carat friendship I felt for Luz Long at that moment.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments