Track and field’s new gender rules could see some females banned from competing internationally

Athletes may have to undertake hormone therapy, compete against men, enter intersex competitions, move to longer or shorter distances or even refrain from participating

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In an effort to address questions about fair play, track and field’s world governing body will publish regulations on Thursday that could force some elite female athletes with naturally elevated testosterone levels to lower the hormone with medication, compete against men in certain Olympic events or effectively give up their international careers.

The rules, scheduled to take effect in November, will initially be enforced in middle distance races of 400m to one mile. These distances, which synthesise the need for speed, power and endurance, are events in which raised testosterone levels can have the most profound influence on performances, the sport’s top officials say.

The regulations are certain to cause further controversy and perhaps bring another legal challenge to the most elemental of sports, in which competition is divided into male and female categories, while biological sex is not nearly so neat and binary.

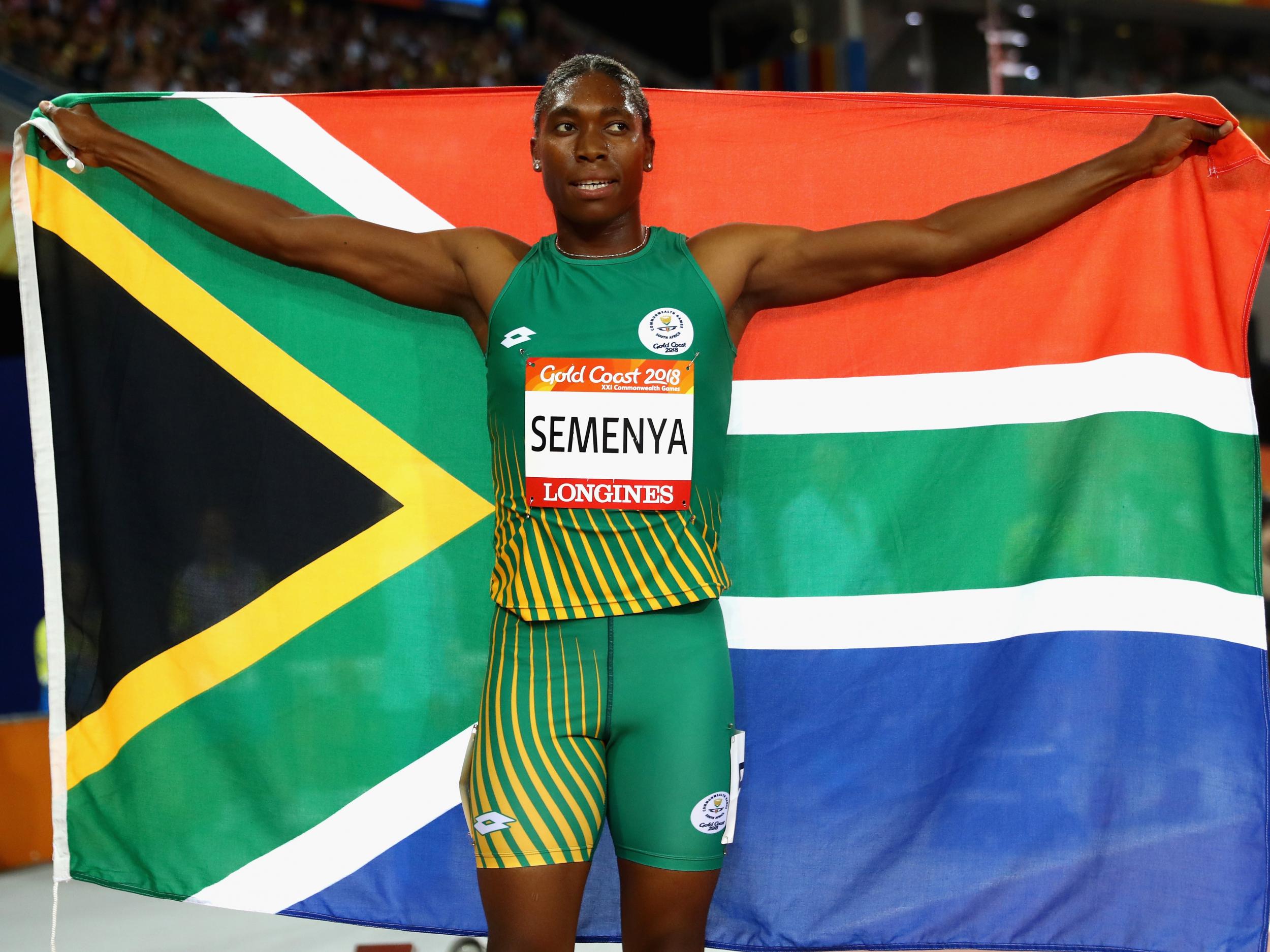

Track and field has gone through contortions on this issue for years, most visibly regarding Caster Semenya of South Africa, a dominant middle distance runner and two-time Olympic champion at 800m.

Female track athletes with elevated levels of testosterone, a condition known as hyperandrogenism, will be required to lower the amount of the hormone circulating in their blood for six months before being allowed to compete from the quarter-mile to the mile in major international events like the Olympics and the world championships.

The affected athletes – characterised in the regulations as “athletes with differences of sexual development” – will then have to maintain those lower levels to remain eligible for international meets.

If they do not, they will be faced with difficult choices – hormone therapy; restricting their performances to national meets; competing against men; entering events for so-called intersex athletes, if any are offered; moving to longer or shorter distances or essentially giving up their chance to participate in the sport’s most prestigious competitions.

The regulations are meant to ensure “fair and meaningful competition within the female classification,” according to track’s governing body, the International Association of Athletics Federations, known as the IAAF.

Athletes will not be required to undergo surgery to lower their hormone levels, the IAAF said, adding that the regulations are “in no way intended as any kind of judgment on or questioning of, the sex or the gender identity of any athlete”.

The regulations will affect female track athletes with naturally occurring testosterone levels above five nanomoles per litre. According to the IAAF, most women, including elite female athletes, have testosterone levels from 0.12 to 1.79 nanomoles per litre, while the normal male range is 7.7 to 29.4 nanomoles per litre.

With testosterone levels between 5 and 10 nanomoles per litre, the IAAF said, women gain a clear performance advantage derived from a 4.4 per cent increase in muscle mass, a 12 per cent to 26 per cent increase in muscle strength and a 7.8 per cent increase in haemoglobin, which transports oxygen in red blood cells.

“To the best of our knowledge, there is no other genetic or biological trait encountered in female athletics that confers such a huge performance advantage,” the IAAF said in the regulations and supporting documents obtained by The New York Times.

The regulations follow a 2017 study, commissioned by the IAAF and published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, which showed that women with elevated testosterone levels gained a competitive advantage from 1.78 per cent to 4.53 per cent in events such as the 400m, the 400m hurdles, the 800m, the hammer throw and the pole vault.

Even a small edge can mean the difference between a gold, silver or bronze medal or finishing off the podium entirely, in events decided by tenths or hundredths of a second, the IAAF said.

The regulations represent an attempt by the IAAF to reinstate rules governing female athletes with elevated testosterone levels, which were suspended in 2015 by the Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport, a rough equivalent of the Supreme Court for international sports.

The court ruled then that the IAAF had not sufficiently quantified the performance advantage gained by athletes with raised testosterone levels. That case involved an Indian sprinter named Dutee Chand. The new regulations would not affect her events, the 100 and 200m.

Much of the debate about female athletes and hyperandrogenism has focused on Semenya, winner of the 800m at the 2012 and 2016 Summer Olympics.

At the recent Commonwealth Games, held in Australia, where Semenya won the 800m and 1,500m, an Australian runner named Brittany McGowan expressed her frustration about competing against athletes with elevated testosterone, telling reporters, “it’s tough for a lot of women in the 800m, 400m and 1,500m at the moment to compare ourselves and be judged by our governing bodies on those times”.

But a study published in April in the Journal of Sports Sciences noted that Semenya’s average faster speed of 1.49 per cent in the 800 fell far short of the 10 per cent performance advantage that men generally have over women.

Paul Melia, president and chief executive of the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport, said in an interview from Ottawa, Ontario on Wednesday that because athletes with hyperandrogenism identify and live as females and present physically as females, “they have a human right to participate in sport in the gender they identify with”.

Mr Melia continued: “If the IAAF applies that policy and a woman whose naturally occurring testosterone falls outside that range, they’re going to say to her: ‘we’re not preventing you from competing. You can compete with males.’ I don’t think that’s right.”

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments