Masters 2015: Augusta and the great class divide - 'We were proud that a black man had won. Very, very happy...'

Tiger Woods is the most recognisable non-white face at this week’s Masters, but on his 53rd appearance as a caddie there Carl Jackson says he has seen changes at Augusta National. In all those years, though, has the club really moved on?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."We were on there illegally, but boys will be boys!" says Carl Jackson, beaming at the memory. He is talking about the days of his childhood, raised with eight siblings in the Sandy Hill neighbourhood, when the temptation to tread the hallowed grass of the Augusta National golf course which bordered the local Rae’s Creek was just too much to resist. They’d catch bream and fry it on a little stove, almost on the banks of the 12th down there, and then step out on to the green.

It was a fateful form of trespass. Jackson, whose less than promising start in life left him seeking makeshift golf practice on open fields and playgrounds, began caddying at the National as a 14-year-old in 1961 and will this week take his final bow after what will be his 53rd Masters.

He’s seen a fair bit; taken a few risks, down those years. He braved a backlash in 1970 by carrying Gary Player’s bag, after the South African had seemed to support the policy of apartheid. Another caddie received death threats after agreeing to join Player and withdrew. But Jackson, by then a young father, “really needed the money”.

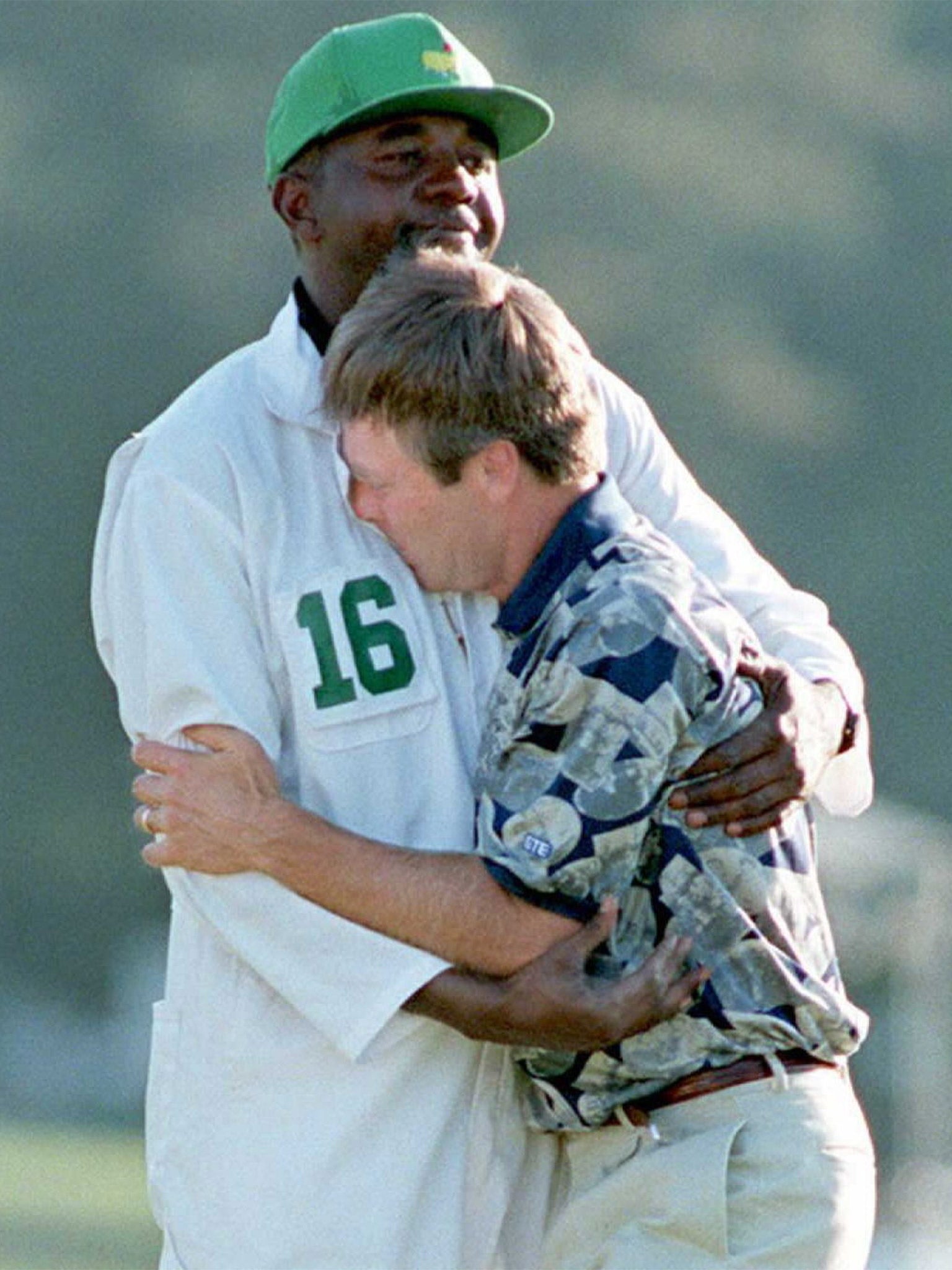

It was six years later that he began his partnership with Ben Crenshaw and it has been against considerable odds that it has lasted ever since, with two Masters triumphs together – 1984 and 1995 – along the way. Augusta made the Masters a far whiter place in 1983 when it abandoned the stipulation that players must use club caddies – the black “loopers” – and allowed the superstars to bring in their friends, all white, to do the job instead.

Jackson vividly remembers the way that those black caddies were eased out that year. There had been a rainstorm in 1982, the caddies were late off the green and had all been told to “put your clubs down by the caddie room, get dry and get home”, he relates, in the soft voice which barely breaks a whisper. There was a shotgun start the next morning and golfers arrived to find their clubs wet. “It was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” he says. “Players were already demanding their own caddies and no one could be forgiving.”

One of the white caddies who began work at that time remembers the effect on the loopers. “It was a killing blow for them,” he says. “They also told members they couldn’t tip the club caddies. They hurt them twice over.”

It was testament to Crenshaw’s foresight that he stuck with Jackson and his intuitive knowledge of the National’s nuances. Their journey concluded with the 68-year-old caddie being presented with the keys to Augusta this week. Jackson and Crenshaw received cut glass bowls before a valedictory pre-tournament press conference at which Crenshaw paid rich tribute to his old partner. “I’ve loved the work and it’s paid my way,” says Jackson.

And therein lies the story of the Augusta National’s complex relationship with race. The racial demarcations of the place scream out to those uninitiated with it.

Black men sweep the carpets in the press room, using willow brooms straight out of the 19th century. The faces of those who serve in the canteen are, almost universally, the same colour. So, too, those who are on hand, with warmth, to spare us the trouble of opening a door. It’s work. It pays their way, too.

And yet to walk amid the “patrons” who line the tee boxes and fairways to watch the golf is to occupy an almost exclusively white space. Walk these acres for the past three days and you would have witnessed perhaps 10 faces of African extraction among those who are here to do anything but serve. This, in a city where 55 per cent of the population is black. It is 18 years since Tiger Woods became the first black man to win the Masters, but his face will still stand out this afternoon.

No surprise all of this, perhaps, since it was only in 1990 that the occupants of National’s inner sanctum finally agreed to alter the 100 per cent white complexion of the place. The mono-racial Shoal Creek club had just been warned that it would be excluded from the PGA tour if it continued to exclude people of colour. Augusta saw the writing on the wall and, for the first time, a black man was allowed through the door in a capacity other than sweeper or doorman.

When Woods clinched that Masters, Jackson anticipated a different complexion to Augusta than the one in which he will be the only African-American teeing off this week. “We were proud to see one of our own come through that day,” he says. “We were proud that a black man won. Very, very happy.”

And though it is not the role of a golf club to institute the socio-economic development of the city outside, Jackson might also have expected the development of one of the planet’s most lucrative sporting events to send out some wealth beyond Magnolia Drive.

The Augusta you will conceptualise – magnolia, yellow juniper, azalea, baize green jackets and turf – actually bears no comparison with what lies down beyond the railway lines on Old Savannah Street, perhaps two miles away.

There are echoes of Detroit down there: fire-gutted clapboard houses, abandoned to their fate; others collapsing in on the inhabitants who stared out vacantly from verandas on Wednesday night. The white exterior of two boarded-up shacks offers graffiti potential. “We hate niggas” is scrawled on both. A roughly fabricated sign – “Stop the black on black crime” – deconstructs any simplistic notions about race and crime around here.

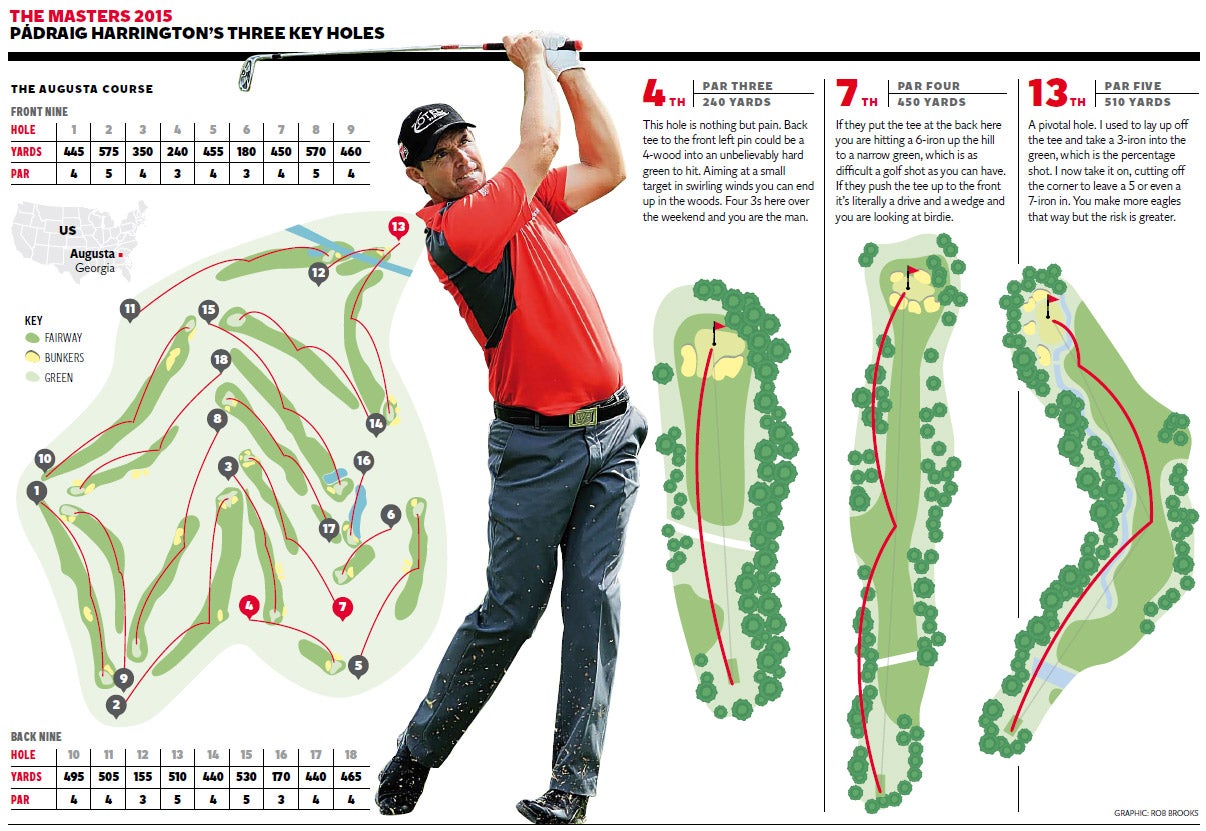

Click HERE to view full-size graphic

Jackson is phlegmatic about the poverty which still stalks the place after all these years. “As a believer in the word of God, I know that word says there is always going to be poor among us,” he says. “There is going to be unjust things in the world. It’s not just the black kids who are poor.”

His outlook reflects the abundance of churches in the network of dead ends that run off Old Savannah: Green Grove Missionary Baptist Church, Good Samaritan Baptist, a dozen more.

His philosophy is that the individuals like him – not the Augusta National – are supposed to make things different. His charity, Carl’s Kids, creates a bridge to golf for what he describes as “under-served” children.

“We are not trying to find another Tiger or [Phil] Mickelson, but good citizens,” he says. “What causes the great divide is education. And we believe that golf can help teach them integrity and how to respect your opponent. It can produce young men and women of good character.”

This is what impassions him, not racial inequality. “Carlskids.com,” he says. “You got that? So any kid in the world can see it.”

It is against the backdrop of Augusta’s exclusivity that Jackson wonders aloud if he will ever get back to this golf course once he and Crenshaw have tackled Amen Corner for one last time on Friday. “I would like to come back with my family,” he says. “But I can’t come back as a caddie and I don’t want to put anyone at the Augusta National on the spot.”

So I put it to Bill Payne, chairman of the club, during his press conference, that some form of life membership might be needed to give Jackson, soul of this place, the same right to return that was bestowed upon Crenshaw as a former champion.

“We don’t have any lifetime membership,” Payne replied. “I’ve been in discussion all week with Ben [about how] he and Carl mark the end of Ben’s career.”

So, might Jackson return in perpetuity, I asked once again. ”We don’t have lifetime membership for employees of the club,” Payne said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments