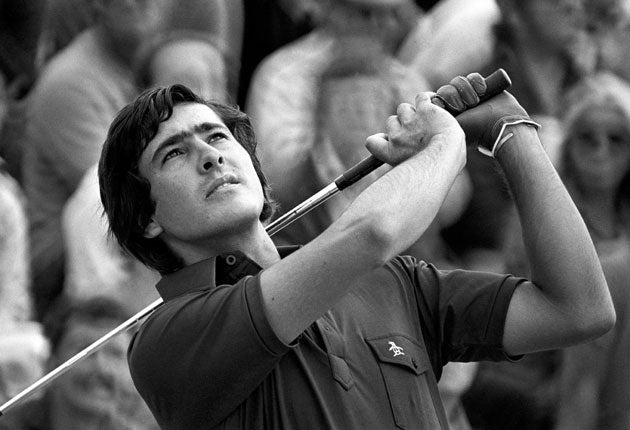

James Lawton: Seve - fierce commitment and uncharted brilliance

Ballesteros's death was more than the end of a great sports career

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The great matador Manuel Benitez announced to his young sister that he would dress her in the finest clothes – or in mourning. His compatriot Seve Ballesteros never made such a declaration. It wouldn't have been appropriate on the lips of a golfer, because when Seve was young the game he embraced as if it was life itself made no great call on Spanish emotions.

Last night, though, we could measure the extent of his achievement because much of his country, and the wide world of sport, were indeed in the deepest mourning.

There were times when the golf of Ballesteros was almost incidental. The passion and the grace and the burning eyes and the windswept hair and the noble head and the wild, fist-pumping self-belief were what commanded the attention of his people as much as the superb anarchy of his play, and they sent a great charge through a game that had never known such fierce commitment and uncharted brilliance.

Ballesteros's death, which came after a typically brave and stoic reaction to the crushing news of a cancerous brain tumour, was more than the end of a great sports career. It was the last sigh of a man who brought a flamenco snap to everything he did, whose life of 54 years was perhaps not so cruelly compressed as it might have seemed at the first news that he had gone. Not, at least, for anyone who had seen the poignant truth that when Ballesteros could no longer play golf as masterfully as a god and, sometimes, as impishly as a street urchin, a central part of his existence had disappeared.

Ballesteros at times hinted as much. His obsession with golf, a game far from the heart of most young Spaniards, was nurtured by the evidence that it could provide a boy of humble stock with a good living, something far above the expectations of his father, who worked on the land around the Real Golf Club of Pedrena on the Gulf of Santander.

Severiano's uncle Ramon Sota was professional champion of Spain four times and once finished sixth at the US Masters, a title his nephew would win twice in a blaze of virtuosity. The boy could see the most desirable of lives and he pursued the ambition as single-mindedly as the torero Benitez, better known as El Cordobes. But there was a price, one he acknowledged in the wake of his failed marriage to Carmen, the mother of his three children, and later the death in a car crash of his girlfriend.

Ballesteros saw more clearly than ever before that when he embraced golf, playing in the moonlight on a course banned to caddies but for one day of the year, he had immersed himself in a game which had brought him unimagined fame and wealth but one that also, when it withdrew its favours, and was no longer susceptible to his fierce will, had left him with a hollow place in the pit of his stomach – and a sometimes almost unbearable pain in his back.

El Cordobes had played with the bulls in the Andalucian breeding fields in the night, a gypsy boy, impertinent and impatient, and Ballesteros fashioned his game, almost completely self-taught, on the forbidden course and then on the neighbouring beach. The bullfighter risked his life; the golfer placed his in a tunnel from which in the end there was really no escape.

That was the truth which, at least in the view of so many of his warmest admirers, haunted the corridors of the La Paz hospital in Madrid, before he died surrounded by his family at his home in Pedrena.

Life isn't a game, of course, but the tragedy behind the glory of Seve Ballesteros was that sometimes he plainly found it hard to distinguish between the two. He wept unashamedly in defeat and was distraught when he finished second as a 19-year-old at the Open at Royal Birkdale in 1976. Ballesteros always lived in the moment, and if such anguish was hard to understand after he had been beaten only by the superstar American Johnny Miller, and tied with Jack Nicklaus, it was soon enough widely understood that the thin, intense youth played only to win. It wasn't considered an ambition; it was a birthright.

He won three Opens along with his Masters titles, and each time he won a major he seemed to journey a little deeper into the improbable, even the surreal.

When he won his first Open, the American Hale Irwin sneered that the Claret Jug had gone to the "car-park" champion, a wild hitter who had had to retrieve his ball from under a car. Ballesteros smouldered and went on to dazzle the world.

Before the range of his genius began to ebb, irretrievably, he was able to produce one last great expression of it. It was in his final major triumph at Lytham in 1988. He overwhelmed the tough and gifted pro Nick Price with golf that was filled with all of his nerve and invention and a touch that was rarely less than exquisite. For his last round he wore a blue sweater, and the banner headline was inevitable: Rhapsody in Blue.

But then if Seve Ballesteros was in some ways a rhapsody that turned into a lament, his meaning was never threatened, not even when his life rushed away these last few days.

When he received the grim diagnosis, he thanked all his admirers for their messages of support and said he would fight with as much courage and serenity as it was possible to muster. Serenity was something that had been denied him for some time, even to the extent that reports of an attempted suicide were not lightly dismissed.

But then if it was true that in his last days Seve Ballesteros found a degree of that elusive serenity, it may have had something to do with the fact that finally he understood quite how he was valued by the galleries he had fought so hard, and sometimes so desperately, to please. There was a time when he seemed to believe that everything he had achieved was finely balanced on the brilliance of his next shot. Of course it wasn't. Few sportsmen on earth had less reason to worry about the meaning of what they had done – and how much they would always be loved.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments