Retiring but not retiring, happy but not happy, Phil 'the Power' Taylor is a web of spinning contradictions

Long read: Darts' most successful-ever player still divides opinion within the sport he dominated. Jonathan Liew talks to the man, the myth (?), the legend

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

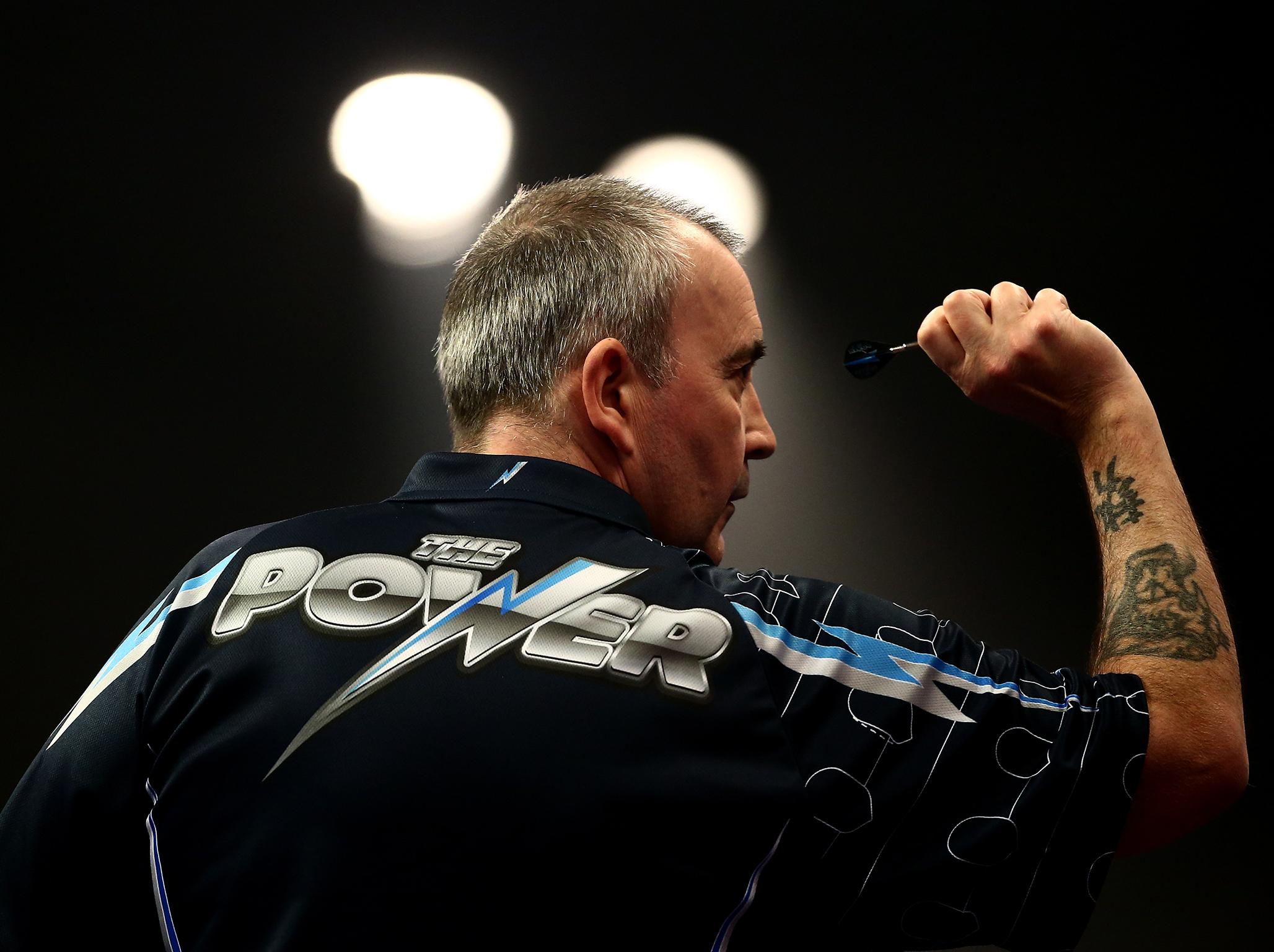

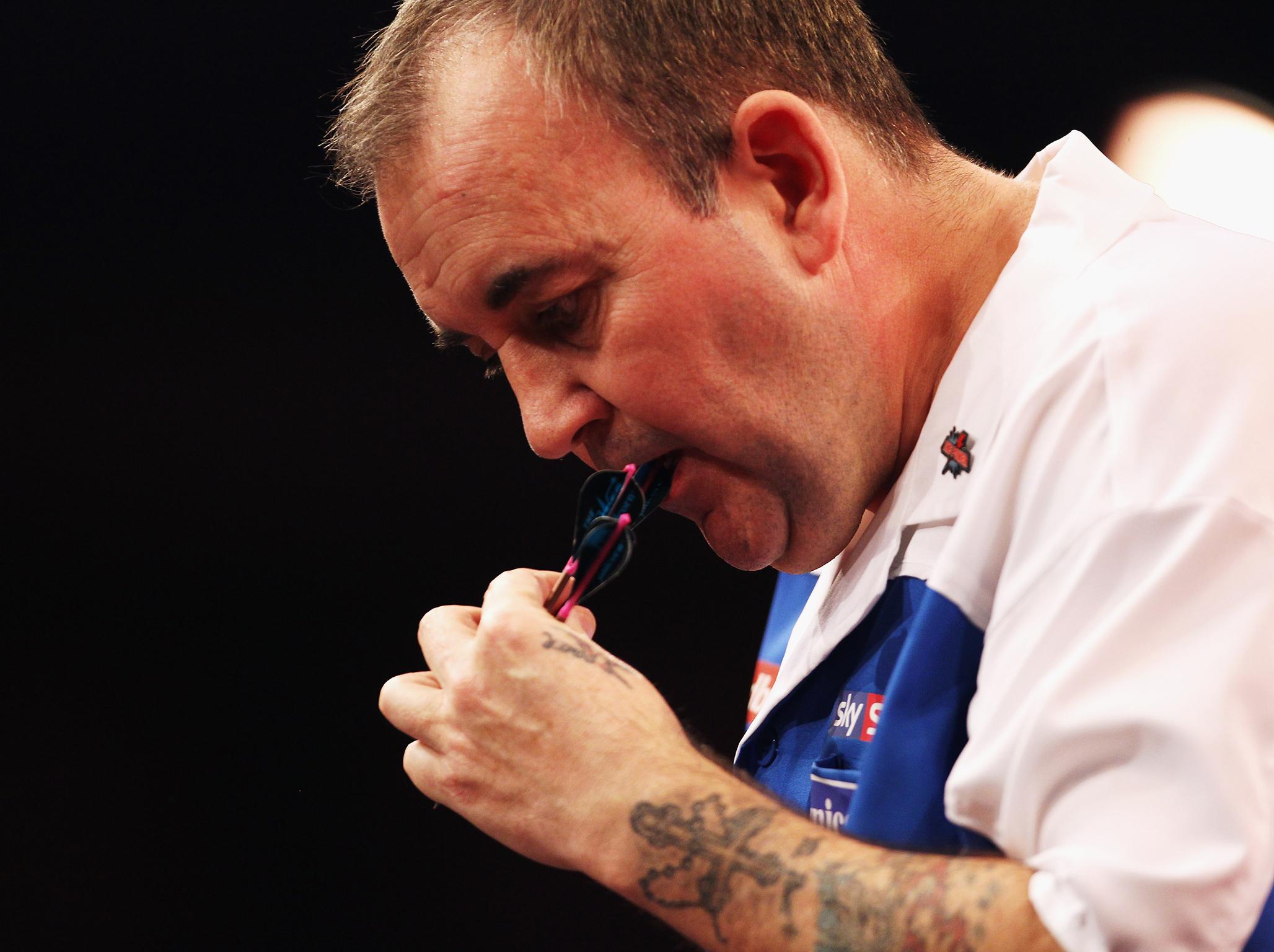

Your support makes all the difference.If you’ve watched a lot of Phil Taylor over the years, you learn to read him. You pick up the tiny, subtle visual cues that offer the merest hint into his state of mind. When he is in full flow, there is a swaying certainty to his gait, a breezy energy to his throw, a haughty menace to his features. At other times, perhaps in a tight game, he will nibble nervously at the flights on the end of his darts. That’s when you know Taylor is stressing.

But sometimes the eyelids droop just a little, his lips flatten, and he takes half a weary breath as he steps up to the board to retrieve his darts. That’s when you know Taylor reckons the game is up. That’s the look that was on his face at Wolverhampton Civic Hall in November, as he stared into the abyss at the Grand Slam of Darts.

Taylor was 4-2 down, first to five. His opponent was a man called Robbie Green, an enormous bald guy from Liverpool with a broad chest and mean, sullen features: a decent player, albeit one Taylor would normally beat in his sleep. But Green was playing well. In the seventh leg, against the throw, he hit 121, 180 and 140 to pile on the pressure, only to watch as Taylor cleared out 93 to reduce the gap to 4-3.

But Green was throwing first in the next leg, and again he began strongly. He threw a 140. Taylor responded with 60. Green stepped up and nailed a 180. Six darts apiece later, Green was sitting on double-18, having already missed a dart for the match. Taylor was stranded all the way back on 245. The crowd shifted forward in their seats. The end was nigh.

Phil Taylor is the greatest darts player of all time, but unless you watch a lot of darts it’s not always easy to grasp what that entails. These days, any half-decent player can reel off 140s and 180s. Of the 32 players at this year’s Grand Slam, 14 of them averaged 100 or more in a game, a benchmark once regarded as the holy grail of scoring. But there’s a reason Taylor has 16 world titles under his belt, why as he approaches his last ever darts tournament at the age of 57, he is still competing at the highest level. For it’s not just about throwing the best darts. It’s about when you throw them.

Taylor steps up and throws his first dart into the dead centre of the treble-20 bed. The second dart was slightly low, but the third nestled in alongside the first. 140, leaving 105. It was better than nothing.

In fact, there’s even more to it than throwing the right darts at the right time. If you can throw the right darts at the right time in the right situation, say just the right words to get under your opponent’s skin, use your own throw to speed him up or slow him down, then you can actually make your opponent miss. And, of course, it helps if you have 16 world titles under your belt.

“It can be in their mind,” Taylor explains. “‘If I do this, I beat Phil Taylor.’ It’s like having to serve to beat Roger Federer in the Wimbledon final. It puts that little bit of tension in the arm.”

For more than two decades, since his first world title in 1990, Taylor has encountered many gifted opponents, some with just as much natural talent as him. But still he won, because he was Phil Taylor, and they weren’t, and they both knew it. He first started noticing this phenomenon, he says, “like 1992, 1993. During the 1990s I was dominating everything. People were saying they were beaten before we got on to the stage.”

Green steps up with three darts in his hand for the match. His first dart misses the double-18 and hits the single. His second dart lands half an inch outside the double-9 bed. His third lands an eighth of an inch inside the single-9. Green gathers his darts and scratches the side of his huge head, unable to explain what has just happened.

But Taylor still has to make 105. He hits the single-19. Then the treble-18. And then, with an awe-inspiring inevitability, he buries the double-16 to level the match at 4-4. Taylor is back from the dead, and no second invitation is required. The game is up, and Green knows it. With a malicious relish, and his tongue firmly lodged inside of his cheek, Taylor throws a 12-dart leg to seal the match. He walks over to Green and plants a kiss on his cheek, like an assassin saying goodnight.

Darts is a game of bravado and bluster, as psychological as poker, as confrontational as an argument, as brutally personal as boxing. In the pubs of Stoke-on-Trent where Taylor learned his trade, there would be glares exchanged, insults thrown, shoulder barges, perhaps even a ruck afterwards. It was one-on-one, man-on-man. A test of will as much as a test of skill. “You had to do your apprenticeship,” Taylor remembers. “Learn your trade. You had to be selfish, cocky, dedicated.”

There is perhaps no other sport on earth so reliant on pure, naked confidence. Michael van Gerwen, the man who has taken Taylor’s crown as the game’s dominant force, had all the talent in the world, but until he started believing in himself in around 2011 and 2012, he was rarely better than mediocre. The colourful Peter Wright invented a whole new colourful persona for himself - Snakebite - in order to conquer his chronic shyness and bring the best out of himself on stage. It is why all darts players have nicknames. They’re a sort of alter ego, a superhero costume that you slip on and off in order to perform.

Occasionally, in competition, Taylor will try a little mental trick. When you are on a number like 182 or 183, with one dart left, the percentage play is to switch to the 18 or 19, in order to guarantee leaving a three-dart finish next time. Usually, however, Taylor won’t do this. He’ll go for another treble-20, even if he misses and ends up on what’s known as a “bogey number”. It’s a calculated gamble, banking on the opponent missing with his next three darts, but it’s more than that too. It’s Taylor’s way of writing off an opponent, telling him exactly what he thinks of him.

It is why, Taylor believes, he reckons he would taken apart even the great Van Gerwen at his peak. “I would have done him,” he says. “Trust me. I would have done him mentally. Confidence beats a lot of people. It’s like when Mike Tyson was at his best. Leon Spinks fought Tyson and you could see as soon as he walked into the ring. ‘Here we go, I’m getting clumped here’.”

Even Taylor’s nickname - “The Power” - carries its own considerable weight, an imperial heft that he carries with him to the oche. As with many players, you suspect ‘The Power’ is simply a well-calibrated character act, a ruthlessly successful sporting persona that has managed to grip darts for a generation.

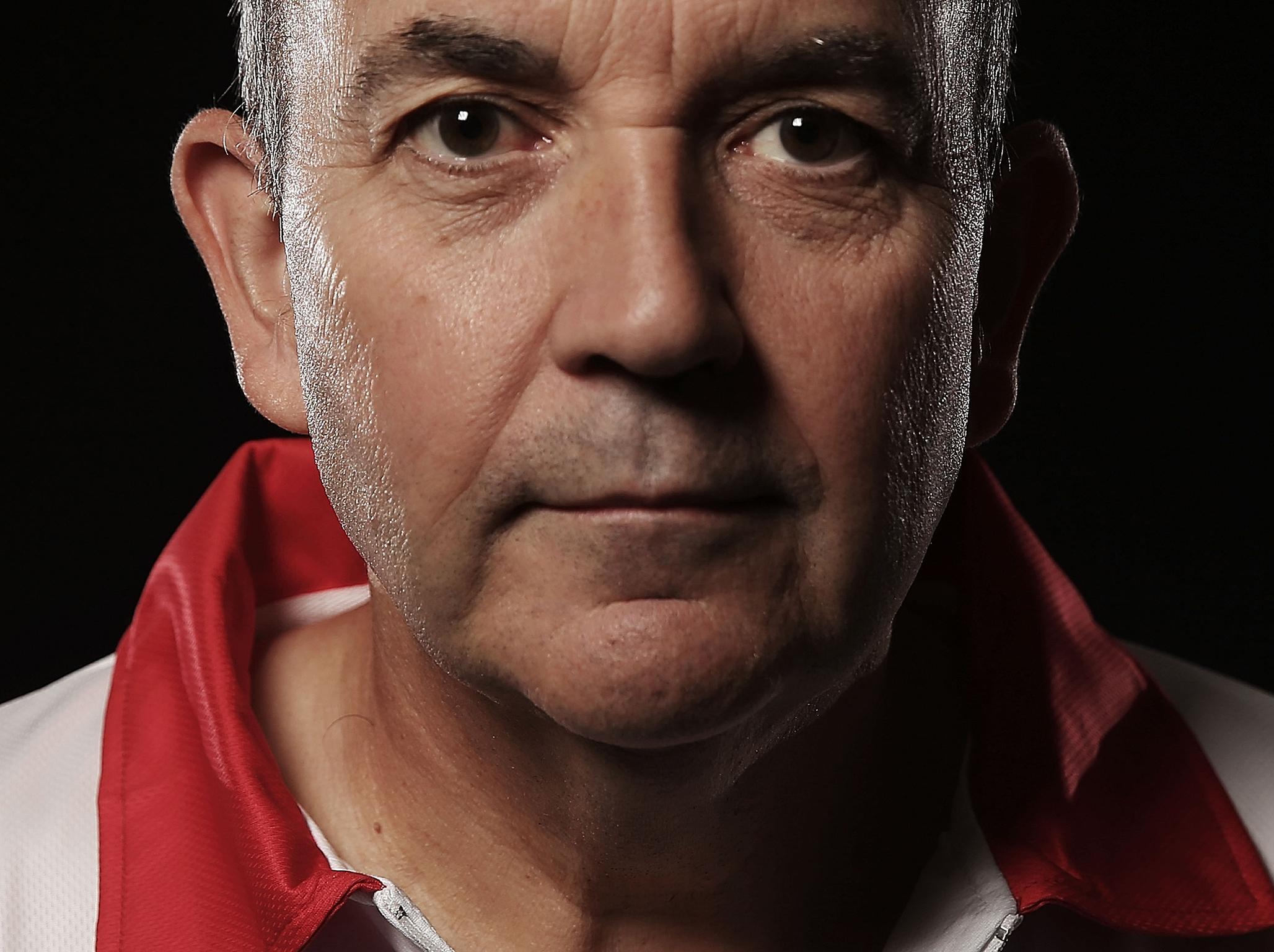

The real question, of course, is what lies underneath. Over the years, Taylor has offered the world occasional glimpses of what he might be like beneath the mask, and the world has not always liked what it has seen.

How did Taylor get so good at darts in the first place? Hard work was one factor. That was something he got from his parents. His father Doug worked in a tile factory, money was scarce, and Taylor tells the story of how his mother Liz would bang on the ceiling to get him out of bed in the morning. If that failed, a bucket of cold water would generally do the trick. “My mum and dad always brought me up like that,” he says. “You go to work, you do your best.”

It was not until his mid-20s that Taylor realised that there was a handy living to be made out of darts - enough of a living, at any rate, to get him out of the ceramics factory where he made beer pumps and toilet handles. “My ambition was just to pay my mortgage off,” he says. “I got a little terraced house, £7,500 for it.”

And so Taylor threw himself into the game, in a way few players at the time could match. He would set himself the target of throwing three 180s every night before bed. On the afternoon of his wedding day, he went to play a county match before returning for the reception. “I used to go into the practice room when I played county,” he remembers. “Sometimes I wasn’t playing until five or six o’clock in the afternoon, and I was there at 9am. The cleaners were hoovering around me.

“‘What are you doing here?’

“‘I’m getting ready for a County match.’ And that’s how it was. I was doing six, seven, eight hours practice before I played. I knew that they wouldn’t.”

You may have thrown a dart. You may even enjoy a game yourself. But the zeal and the stamina to play for hour upon hour, day upon day, year upon year: that, in many ways, is what has distinguished Taylor from the rest. “I used to watch them,” he says. “Half an hour into the game, they’d dropped their standards. They weren’t putting the effort in. It’s like running.”

And yet, as the trophies and the cheques began to accumulate, as Taylor became not just the game’s best player but to a point of embarrassing dominance, he refused to stand still. He experimented with new darts, new flights, new stances, new tactics. He would watch videos of other players - even today, hardly anybody does this - in an attempt to accustom himself to their pace and style. He would adjust his walk back from the board depending on whether he was playing a fast or slow thrower.

At every turn, you get the impression of a mind constantly thinking, constantly striving, never satisfied. This is an impression reinforced when Taylor is asked - after 16 world titles, 16 World Matchplays, six Premier Leagues, six Grand Slams, 11 televised nine-dart finishes and a quarter of a century at the top of the game - what mark he would give his career out of 10.

“Seven,” he says.

What?

“Yeah. I lost four finals. I know what I did wrong. I was lazy at times. I got fed up with it, bored. Like you do with any job.”

The interesting question is why he is retiring now. He is ranked No6 in the world, and could very easily carry on for a few years, still win the odd pot, still make a handy living, possibly even another world title. Or he could have retired while still at his very peak, back when he was still unbeatable, back when his name would cast a menacing shadow over the rest of the draw. So why now?

“I can’t keep the schedule now at my age,” he explains. “You’re tired all the time. I’ll go to hotels and can’t sleep properly. The next morning, you’re bloody knackered. All these youngsters are skipping around like fresh young daisies. I used to get up in the morning to practise. I was fanatical with it. Now I hardly practise at all.”

Two days after the end of the World Championship, Taylor will fly to Germany for a lucrative exhibition event. Then five weeks in Australia. Then a soft-tip darts competition in Japan, then Abu Dhabi, Dubai, North America, New Zealand, even Vanuatu in the south Pacific. At any rate, for a man seemingly exhausted by life on the road, his post-retirement plans hardly suggest an aspiration to stick his feet on a pouffe and sit back in front of Sky Sports News.

“I’ll be busier than I am now,” he claims. “Next year we will are doing about 160 nights on the road. I’ll still earn a fortune, still be playing in front of 3,000 people. I’d do the jungle [I’m A Celebrity - Get Me Out Of Here!]. Strictly, I’m not sure. But we have been asked to do the jungle in the past.”

Taylor has made millions from darts over the years, and although he clearly doesn’t need the money, it is still something that seems to preoccupy him. In a way, it is one of the few things that still does. “Sometimes I am disappointed if I get something new, like a house or a car,” he says. “I’m not excited about it. It doesn’t mean anything. These things are possessions. I would rather stay at home and do normal things, go to my Aldi and Lidl.”

Taylor will go for his 17th world crown at Alexandra Palace, which has now hosted the PDC World Championships for a decade. A total prize fund of £1.8 million will be up for grabs, and players have qualified from every continent on Earth. It is a long way from the first PDC championship in 1994, in which the winner took home just £16,000, and all the players came from Britain, Ireland and America.

Without Taylor, the PDC would never have become the global superbrand it is today. Without Taylor, it is doubtful whether it would even have got off the ground. The fledgling organisation was fighting a protracted legal battle with the British Darts Organisation, from whom it was attempting to break away, and was out of cash. Taylor lent them £40,000. “It was the last money I had,” he says. “We had no choice, really. It was shit or bust. But there wouldn’t have been a PDC without me.”

The reason for mentioning this is that as Taylor surveys the darts landscape today, on the eve of his final tournament, it is impossible to underestimate the sense of ownership he feels towards it. He is not the favourite to win - van Gerwen is - and although he is still the brightest star in the sky, his name no longer carries the awesome aura it once did. For the first time, Taylor sees a game that is no longer dependent on him, and has mixed feelings about it.

“Never in a million years did I think it would get this big,” he says. “I think we’ve peaked now.”

It seems an odd thing to say, given the inexorable growth of darts over the last decade and more. But Taylor warms to his theme. “The characters are going,” he says. “They’re like robots now. Half of them can’t smile. There are a few young players who I do like. Rob Cross is very good. Jamie Hughes is very good. Corey (Cadby) isn’t there yet. If I spent six months with him, I would turn him around. Max Hopp has a good style, lovely throw. But they don’t have it mentally yet. They have got to get that right.”

Perhaps Taylor is simply telling it as he sees it. But it is possible to spy in his words a certain light distaste towards the idea that the sport might rattle serenely on without him. Perhaps you might even say he is slyly envious of the next generation; as if they were children picking fruit from a tree he planted many years ago.

After beating Green at the Grand Slam of Darts, Taylor was still on a high as he did his post-match interview with Laura Woods on Sky Sports. Woods tried to explain to him that he still potentially needed three legs from his final group game to qualify for the second round. Taylor was puzzled. “Why have I got to get three legs? To win the group?”

“To come first or second,” Woods replied.

“You don’t know, do you?” Taylor challenged her with that half-playful, half-aggressive grin of is that has the habit of making other people in the room feel just a touch awkward. “Well, I’m going to try my socks off tomorrow. I can’t say bollocks, can I?”

“You just did,” said an unimpressed Woods. “We have to apologise for that. What a great interview,” she added as Taylor walked off. “Glad we did this one live.”

The whole thing lasted less than a minute, but it encapsulated why, for all the trophies and the legacy, the moments and the memories, the massive, unrepayable debt darts owes Taylor - there is still a significant portion of the darts community that has always struggled to warm to him. For most of the abundant years, you could put this down to the inevitable tedium of having the same guy winning tournament after tournament, year after year. But for a player with so much credit in the bank, he retains a habit of rubbing people vaguely the wrong way.

Uncomfortable post-match interviews are just one of the constituent parts here. Petty spats at the oche - doubtless a legacy of the Stoke pub scene - have been another. But there is also a far more sinister element in Taylor’s past that continues to colour people’s opinions of him. In 2001 he narrowly escaped jail after being found guilty of indecently assaulting two 23-year-old women in his caravan after an exhibition tournament in Fife. Taylor denied the accusations, but a Scottish sheriff described the women as “credible witnesses”, and fined Taylor £1000 for each offence.

The aftermath of the trial sent Taylor into deep depression. And for all he has achieved - the fairytale story of a self-made working-class millionaire from Stoke - you occasionally wonder: darts has made Taylor famous, it has made him rich, but has it truly made him happy? “It’s your dream,” he says. “It’s everything. You get a trophy and a cheque. Then: is that it? It all goes quiet. Then about five days after, you start crying. You go all emotional as if someone has died.”

Taylor’s father died in 1997. His mother lost a short battle with a lung infection in 2015. He divorced his wife Yvonne in 2014 and fought a long legal battle in the subsequent months. His children are grown up and he has spent most of the last 20 years travelling the world. His only real companion is his manager Bob, who travels on the road with him, more for the company than anything else. And although he claims to be sick of media appearances, Taylor still clearly loves an audience. So does he feel that his single-minded obsession with darts has cost him in some other, important respect? Does he miss that human connection?

“There are a few things I would have changed about my life,” he says. “Of course I would. Life is life. No good looking back. If I go back, I would have changed things. Of course, I would have done.”

You sense a confession coming. But it's not the one you're expecting.

“I would have invested money in different places,” he goes on. “I would have invested in property in London. That’s how you make money. A friend of mine bought a two-bedroom flat. £1.3 million. You get that for £40,000 where I live.”

How badly did the court case affect him? “It affects you at the time,” he answers. “I can’t talk about it, because it would get me in trouble.”

And with that, after an hour of fluent conversation, Taylor swiftly gets up and abruptly ends the interview, grabbing his steak sandwich as he leaves the room.

As he departs, you’re really none the wiser. Like all of us, Taylor is a web of spinning contradictions. He’s retiring but not really retiring. Happy but not really happy. Fine for money and yet still weirdly preoccupied with it. Surrounded by plenty of people, but close to very few. Perhaps the price of genius is that nobody truly understands you. Or perhaps the price of indulging genius is that you never truly get the time to understand anyone else.

One answer of his, in particular, stood out. Taylor has won everything in darts. He’s come second in BBC Sports Personality of the Year. He has houses, trophies and memories. What possible accolade could you give the man who already has everything?

Taylor smiled. “A cheque,” he replied.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments