Washington Redskins name change: A red-hot issue of race, money and politics

Opposition is growing to the Washington Redskins name, while the club have launched advertising and fund-raising campaigns in attempts to sway opinion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The complexity of the debate which consumes Washingtonians like never before is written through the crowds at the stadium of the sports team which finds it increasingly hard to brush away.

It surrounds the city’s American football team, the Washington Redskins, whose games still empty the city of its traffic but whose name is seen increasingly as disparaging to Native Americans. The list of high-profile individuals demanding it be changed grew a little longer this week when the former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared that it was “insensitive” and that there was “no reason for it to continue as the name of a team in our nation’s capital”.

Her contribution came after Jordan Wright, the granddaughter of George Preston Marshall, who brought the professional football team to Washington DC from Boston in 1937 and changed its name from Braves to Redskins, made her first, hesitant contribution to the debate. “It’s about respect,” Wright told the Washington Post. “If even one person tells you that name, that word you used, offends them, then that’s enough. That should be enough.”

And then you attend the FedEx Field stadium – with the 61,000 people who watched Manchester United and Internazionale play there on Tuesday night.

“The name and the team have been here so long. It doesn’t mean ‘Native American’ here,” says Charles Clark, of African extraction.

“Does it disparage anyone? It just stands for the team we love. Simple,” adds Roy Schapiro, who is of West Indian descent. The Independent’s straw poll puts these pro-Redskin men marginally in the minority – four to 10 – but their voices scramble the search for neat moral parameters and explain why the arguments have been raging again this week.

The debate has intensified since an emotive Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian symposium last year on the use of Native American imagery in sport drew an audience of 300.

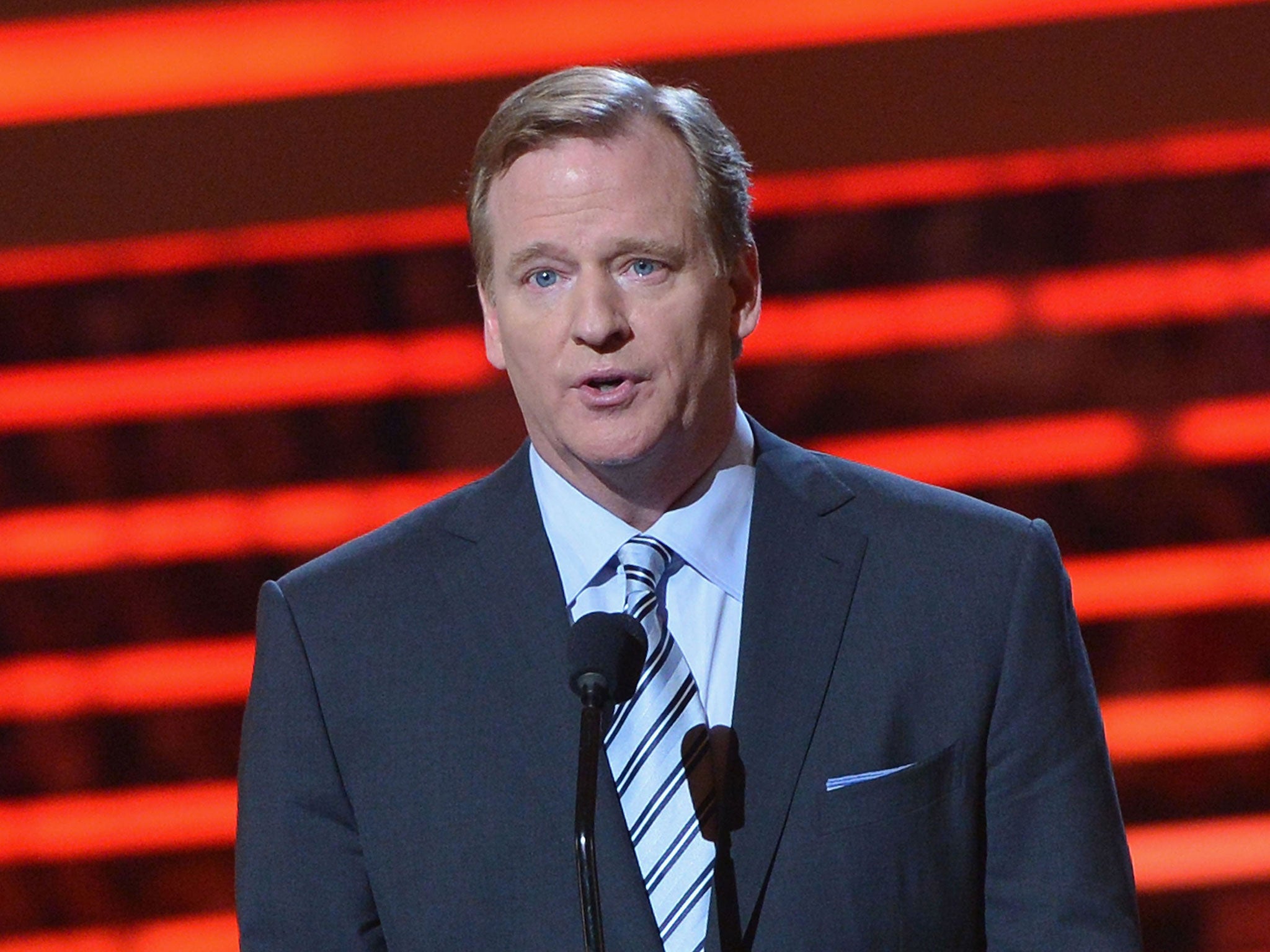

A young man who had shown up in Redskins gear hurled it to the ground in solidarity. Journalists had already started to drive the demands for change by then. Sports Illustrated’s Peter King and the Washington Post’s Mike Wise are among many who refuse to use the name. When 50 US senators wrote to the National Football League calling for a name change, its commissioner, Roger Goodell, offered only qualified support for the franchise, declaring: “If one person’s offended, we have to listen.”

The team’s owner, Daniel Snyder, desperate to hold on to his intellectual property, subscribed to the Vincent Tan and Assem Allam school of negotiation for a time. “We’ll never change the name,” he said. “It’s that simple. NEVER. You can use caps.”

But in the last 48 hours, the club have gone on the offensive. They have launched a campaign to defend their name, headed by a five-strong phalanx of former players – Gary Clark, Chris Cooley, Mark Moseley, Ray Schoenke and Roy Jefferson – three of whom travelled to a Native American reservation in Montana this week, to launch a PR offensive and promote survey results to show that these people are for the name. Aspects of this initiative are wholly unconvincing. One member of the Turtle Mountain Band of the Chippewa Indians, Dustin White, said that when the tribe filled out the survey sent to reservations across the country last year, leaders did not know the Redskins were behind it, though he welcomed the partnership. In Turtle Mountain, there are material benefits to backing Snyder’s case. The Redskins’ foundation has provided 150 iPads for local schools and has been building a new playground on the reservation, scheduled to be completed this week.

“When you see these kids running up to this playground with big grins on their faces, you know it’s worth it,” said White. The Redskins also sponsor a 33-member reservation rodeo team that travels the country to compete. The campaign has been backed by ads for a new website, RedskinsFacts.com, which have started appearing on the websites of Sports Illustrated, the Washington Times and Washington Post in the past few days.

This may not be enough. The many demanding change include President Barack Obama, while the development which inflicted pain on Snyder was the US Patent and Trademark Office’s decision to cancel six of the team’s registered trademarks, declaring the word “redskin” disparaging. That makes it open season for those seeking to produce imitation merchandise. Marshall, a laundry store magnate who bought the team for $2,500, was known as one of the last NFL franchise owners to integrate black players into the team and only did so after he was threatened by the federal government.

The discussion of alternative names has already been exhaustive: “the Senators” (drawing on an obvious political connection), “the Federals”, “the Braves” (a less demeaning way to acknowledge Native Americans), “the Redhawks” (the same change that Miami University made 20 years ago) and, most simply, “the Skins”.

“The subtraction of three letters – R-E-D – simultaneously addresses the two most important issues being argued over in this debate: it removes from Washington’s nickname the offensive part of the word that describes a Native American’s skin colour,” says Sports Illustrated’s Don Banks. “A Redskins fan has already called their team the ’Skins for probably as long as they’ve been fans. It’s not a drastic, wholesale change to another name, and it leaves Washington with some ability to give a nod to its team history and identity.”

An academic paper, “I am a Redskin”, by Ives Goddard, senior linguist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC, complicates the issue, concluding that the colour red was being used by natives to describe themselves in the Illinois region from the 1720s. There were few primary colours identified and available for them to use, back then, and red would not have had different connotations, he says. It could have meant earth-brown. There is evidence of the term being used in a letter by a Native American in 1769 and again in 1809, when a tribal leader, French Crow, stated: “I am a red-skin, but what I say is the truth.”

But the pressure for change is beginning to look irresistible in a nation where baseball’s references to Native Americans – from the Cleveland Indians’ cartoon mascot named Chief Wahoo to the Atlanta Braves’ tomahawk chop gesture – have also earned censure.

The Washington Post’s Mike Wise best captures the prevailing sentiment. “I can see how a lot of people in Washington, including the owner, grew up loving the team and never used the word in a disparaging way towards American Indians,” he says. “I can see that’s part of their history and I don’t think they’re racist because they use it. But why can’t the owner and the most ardent fans of the name put themselves in the shoes of someone else?”

The name has a connotation that “doesn’t make us look civilised” says fan Gene Stevens, leaving the stadium with his family after watching United’s win over Internazionale. “You can find all the excuses and all the people you like to say ‘it’s fine’. But you need to sit down and think about how you look to the wider world.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments