The Last Word: Writing is on the wall for pedlars of old school nous – so prepare to take notes

Everybody says there’s no 'I' in team. But there is in win. Individuals are key

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In A Chump At Oxford – having sought an education, because "we're not illiterative enough" – Stan Laurel is ultimately revealed as the amnesiac Lord Paddington, the greatest athlete and scholar in the university's history. As he imparted a spot of Govan street sense to the Harvard Business School, it was hard to resist a similarly gratifying transformation in Sir Alex Ferguson.

Post-Moneyball, American sport is increasingly self-conscious in its sophistication. In jargon and ethics, coaching methodologies are expected to reflect enlightened capitalist values; to break down the physical and mental capacity of athletes and organise their optimal impact on a market that converts points, or goals, into billions of dollars.

Ferguson instead confirmed himself a champion of the old school, not to mention the Old World. He expressed contempt for taking notes during a match. Players would not be impressed if he consulted a piece of paper at half-time and said: "Oh, in the 30th minute, that pass you took…" The withering implication is that affectedly "modern" coaches use a veneer of sophistry to disguise feeble personal authority. And that, presumably, is about the last thing a bunch of academics wanted to hear.

But succour is at hand. On Monday, another great coach seeks fresh mystique for one of sport's most dramatised training philosophies. Already winners of two college football championships in three years, Alabama meet Notre Dame in a final saturated with past, present and future consequence.

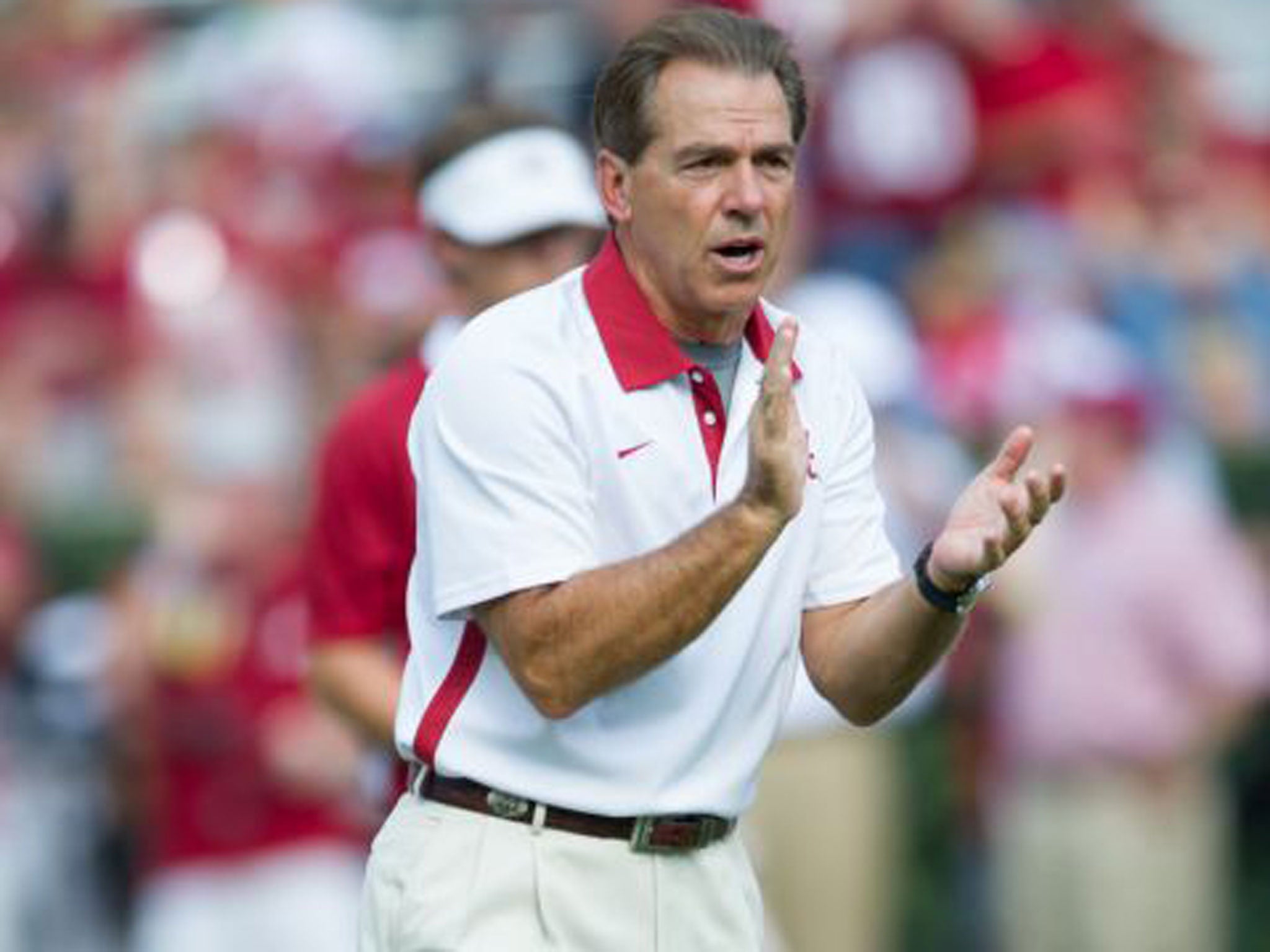

The future concerns Nick Saban, whose rumoured departure to NFL is filling American sportspages. The past demands redress for the great Bear Bryant, the "simple plowhand from Arkansas" who coached Alabama to six national titles between 1958 and 1982. Bryant lost consecutive finals to Notre Dame – notably an epic in 1973, when the Irish stemmed the Crimson Tide 24-23. But the present is all about "The Process".

Funnily enough, Saban seldom uses the term himself. And his players and staff struggle to put it into words. But you can bet Harvard would be more comfortable with "The Process" than a compendium of stony Glaswegian axioms. Sure enough, Saban has been reverently featured by international business magazines, and other American football coaches have become obsessed with his system.

In essence, "The Process" reduces ends to means. Your best chance of reaching your destination is to focus, not on the horizon, but on each step. In 1998, travelling to the undefeated No 1 team, Ohio State, Saban's unranked Michigan State caused a huge upset. He had told his men to forget the score and simply see through each play, respecting its own intrinsic validity. Never mind what happened in the last phase, win the next one. His team played with such freedom that Saban resolved to extend the approach to every dimension of his regime.

"The Process" animates every increment, not just in competition but in conditioning, recruitment and profiling. Saban is always looking for an angle. He has hired actors to hone improvisation and communication. He has tried martial arts and pilates. He has brought in psychologists, motivational speakers. Though college football is very big business – the Bryant-Denny Stadium seats 101,000, while Saban is reportedly on $5.6m (£3.5m) a year – he must observe tightened recruitment constraints. But Saban meticulously explores all permitted prototyping and prospecting. "Everybody always says there's no 'I' in team," he says. "But there is an 'I' in win, because individuals make the team what it is… It is damn important who these people are, and what they are."

In his defense room hangs a slogan borrowed from his mentor, Bill Belichick, in the 1990s: "Do Your Job." If each cog functions, the machine will do its thing. The same applies to personality. Though supervising young men on the cusp of fame and fortune, Saban expects scrupulous manners, appearance and standards. One coveted quarter-back signed for him because Alabama players removed their hats when introduced to his mother. For the last three years, Saban's students have been second in the South-Eastern Conference graduation table.

"The Process", plainly, is not for coaches embarrassed by writing things on paper. Of course, it is not as though Ferguson's way is obsolete. True, sheer length of tenure places him in too unique a position to serve as much of a model for others; but Harry Redknapp, with his scoffing anti-intellectualism, also retains the respect of the professional community. Even so, the suspicion remains that Redknapp's replacement at Spurs, by Andre Villas-Boas, accelerated an irreversible trend. The American owners of Liverpool, for instance, shortlisted a young manager who has even used hypnosis, Roberto Martinez, and a prolific scribbler, Brendan Rodgers.

So while the writing may not be on Ferguson's own notepaper, it is surely on the wall for his generation. Who knows? Some day the Harvard Business School might even end up passing that paper on to the Department of Palaeontology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments