The Last Word: Match-fixing must be fought as fiercely in sport as doping

In countries where players face intimidation, the problem is

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just days after Australian police busted a match-fixing ring in lower league football, the Singaporean authorities took action against an illegal betting ring headquartered in their backyard.

Tan Seet Eng, known as Dan Tan, has long been cited as the chief organiser of a network of fixers operating primarily in Italy and eastern Europe but has outrun the authorities by falling between the cracks in international jurisdiction.

The fight against this kind of corruption is made even harder by the fact that match-fixing is hard to prove. Not only is it subjective (did the goalkeeper deliberately concede a goal or was he fairly beaten?) but there is rarely a paper trail. Few police forces have the resources or the inclination to build cases.

However, on the evidence of this week, there is clearly – belatedly – a crackdown led by transnational agencies on some of the rogue elements exploiting the worldwide popularity of the game.

It is part of a long overdue acceptance in sport that corruption threatens its very existence if left unopposed. For too long, the authorities have seen the scourge of doping in isolation.

It is by no means wrong to chase down the drugs cheats. The battle there is still far from won. Dopers continue to thrive at the very pinnacle of their sports. Lance Armstrong, Tyson Gay and Asafa Powell are just the tip of the iceberg.

But they must be viewed as part of a bigger picture of corruption. Is fixing a game not just as bad as juicing yourself up? Both cheat honest opponents of a fair contest.

Until now, the answer has been no. It is changing, though, as sports’ governing bodies strengthen their ethics guidelines under political pressure and the weight of public opinion.

It went totally unnoticed this month that UK Sport, the funding agency for elite athletes, published a consultation proposing to make match-fixing as much of a crime as doping. In a significant change to its eligibility rules, athletes found guilty of illegal betting or match-fixing face a lifetime ban on public funding. Previously, the suspension of a grant only applied for as long as that person was serving a ban or a prison sentence.

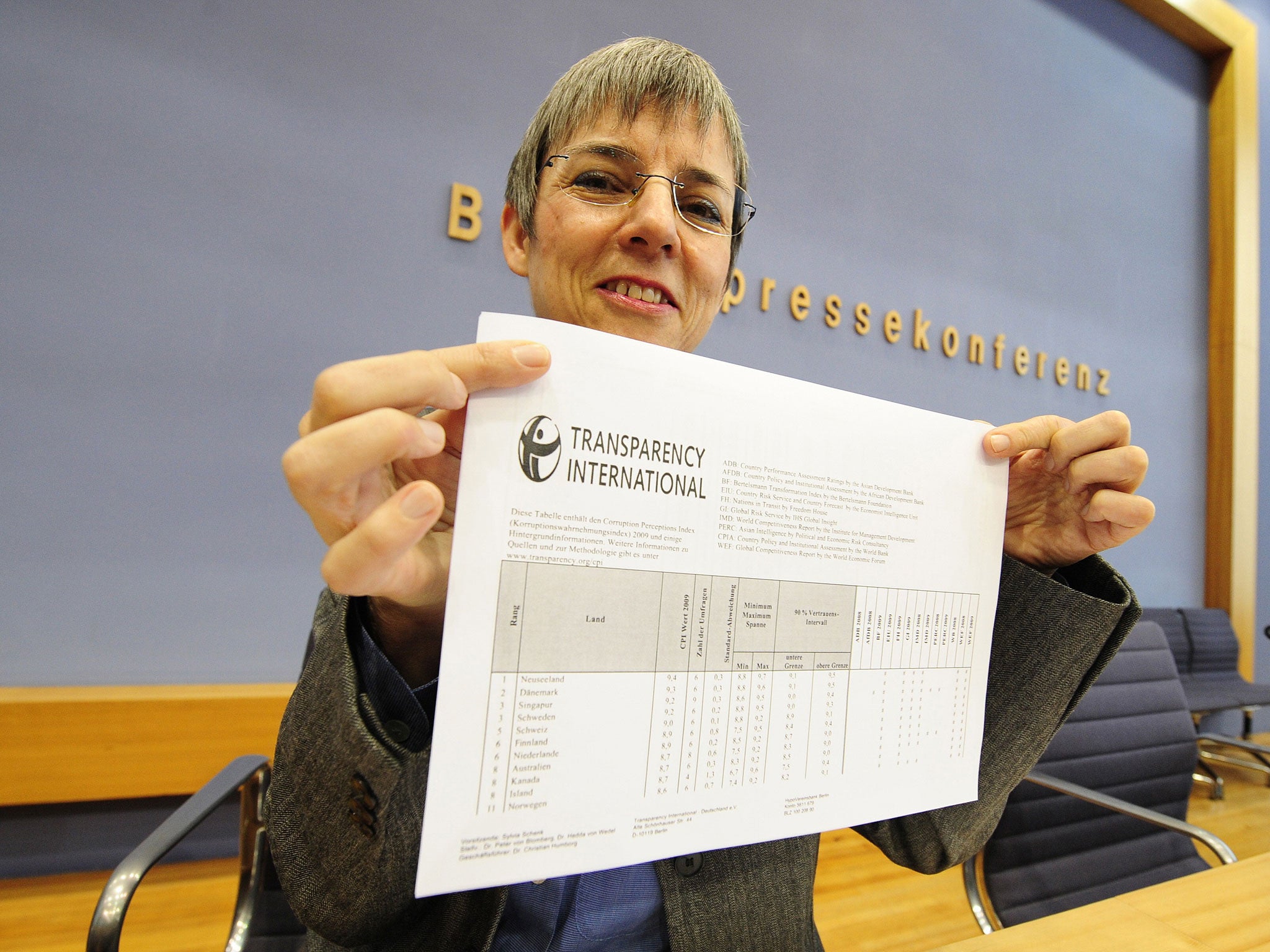

Coincidentally, I was invited this week to Berlin by Transparency International (TI), the anti-corruption NGO, to speak at a seminar on match-fixing. As part of a European Commission-funded project, TI is working with European leagues to devise educational programmes for players, and media strategies to deal with the consequences of corrupt activities involving their competitions.

Germany – chastened by the Bochum case, the biggest prosecution of match-fixing to date – is leading the way. Other countries, such as Greece, which had its own scandal to deal with in 2011, are playing catch-up after finally acknowledging that they have a problem.

I will admit to having been a sceptic myself. I think that – compared with doping – match-fixing is often an overstated issue. Drug-taking is much more widespread and we should not take our eye off it by diverting precious resources.

Another excuse to dismiss it is that it is too merrily leapt upon by headline-seeking politicians and opportunistic sports administrators seeking to create yet another pointless working group.

I concede this is a western perspective further skewed by coming from a football culture where for decades bungs were tacitly accepted as normal business practice. In the UK, where we are inured to the idea that parts of football are bent, it is largely restricted to the invisible lower leagues where the temptation to make a few thousand quid is too strong for low-paid journeymen. Hence, our instinct to marginalise it: “What’s the harm in a few bets on a red card, anyway?”

Such indifference was roundly challenged by Sylvia Schenk, TI’s senior sports adviser, who argued that the growth of internet betting and the increased involvement of large-scale money launderers had turned match-fixing from a one-time petty misdemeanour into a web of serious global criminality. In countries where players and their families face intimidation by criminal gangs for refusing to throw games, the problem is very real.

From a woman unafraid to stand up to the likes of Fifa’s president, Sepp Blatter, and the former president of cycling’s governing body, the UCI, Hein Verbruggen, I should have expected nothing less than a robust rebuke.

She is right, of course. Just because something is difficult to address, doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be if it is the right thing to do. The obstacle, however, is priorities.

When national anti-doping budgets are being cut against the backdrop of tough economic choices by governments, what hope do anti-corruption campaigners have of getting funding for their fight?

The answer is that match-fixing and doping should be seen as symptoms of the same malaise. Tackling both in equal measure is a good start to restoring the spiritual health of sport.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments