Steve Bunce on Boxing: Punchy spoilers preferable to shameful charlatans of yore

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is no science or set of rules attached to the sport of heavyweight boxing and becoming a rich champion is as random as a raffle.

David Price found out the hard way last weekend against Tony Thompson that careful matchmaking, being a star and standing 6ft 8in tall are not enough to walk into fame and glory. A decade ago the seemingly invincible Klitschko brothers both found out the Price way that all the advantages are helpless against a bit of old-fashioned punching power. They came back stronger and better.

Thankfully, there are also no outrageous illegal deals in the modern sport of boxing that exclude certain fighters from getting what they deserve. The business might operate in a murky twilight of confused morals but it is not criminally corrupt. It was a very different landscape in the Fifties and even the early Sixties, when a dozen or more terrific heavyweights either missed out on a championship fight or were granted an audience with the champion too late.

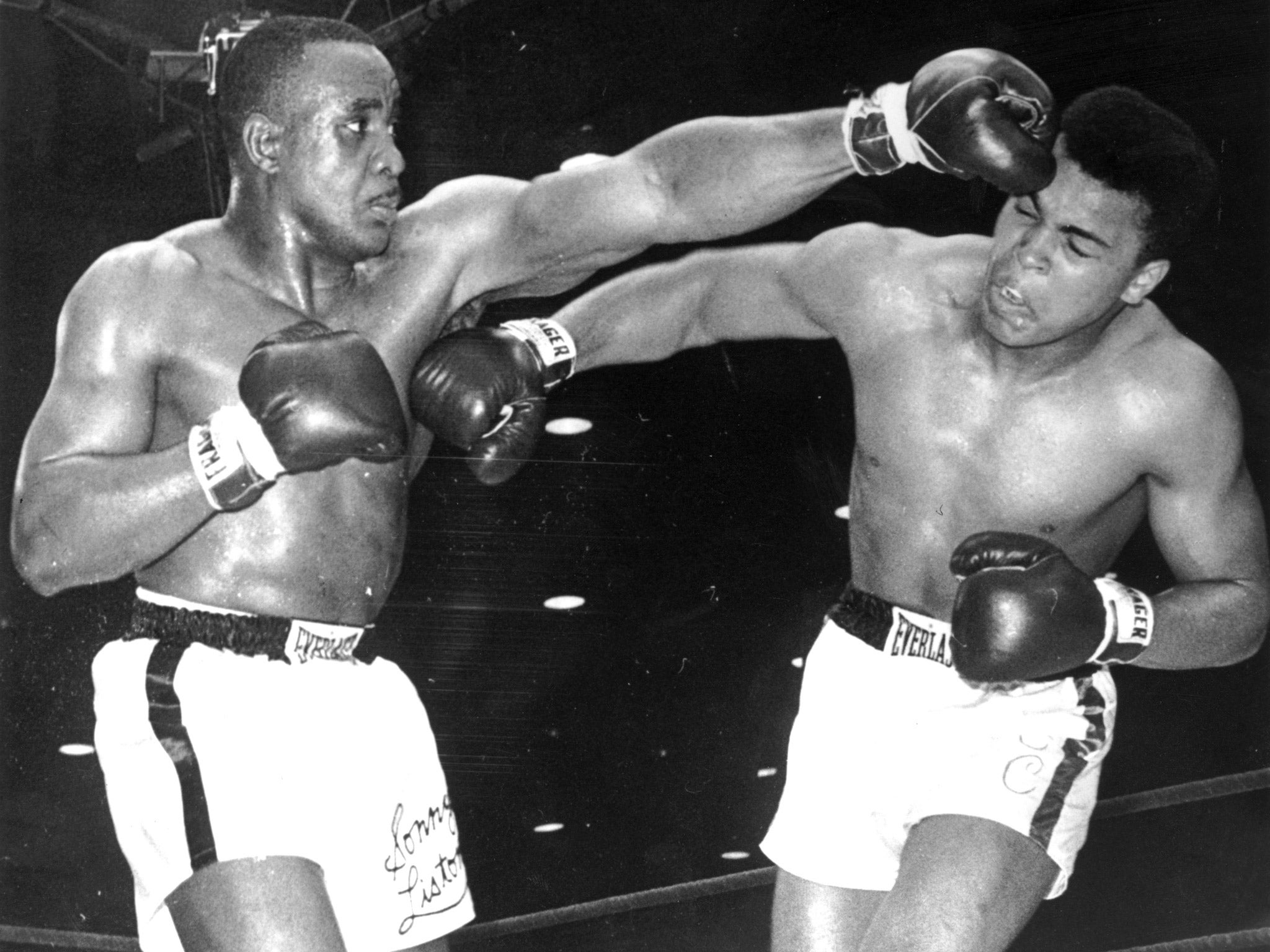

It was into the middle of this confused and prejudiced world that Sonny Liston fought his way from nowhere to the title, a journey he completed after an outrageous series of hard, hard fights; Liston, a little bit like Jack Johnson 50 years earlier, met all the hard men, the avoided bangers and the easy-to-ignore sluggers.

It is too simplistic to adopt the "it was harder in my day" approach to analysing boxing, but it was most definitely harder before about 1970 for fighters to get a fair crack at world championships. The exclusion of most black fighters before then was outrageous and a more detailed look at the scrap heap of the forgotten would make disturbing bedtime reading. There are some fighters who were potentially great still being discovered 50 and 60 years after being avoided and left to rot by a boxing business that was crooked and evil.

Liston had his established connections with various criminals, shadow men who operated his career, but he was still thrown in with fearsome fighters like Nino Valdes, Zora Folley, Cleveland Williams and Eddie Machen before he was finally given a world title fight against Floyd Patterson in 1962. Patterson had avoided most dangers, feasting on men like Pete Rademacher, Tom McNeeley, Brian London and a ruined fighter called Tommy Jackson. Liston waited about three years for his shot; he was in an invisible line with Machen, Folley, Williams and Valdes. It was a disgraceful period in sport and I would rather the often false mannequins of today's business than a return to the shame.

Liston ruined Patterson in two title fights, one each in 1962 and 1963, and was then manoeuvred into a fight against a kid called Cassius Clay. That fight took place on 25 February 1964 and ended with Liston sitting out after five torrid rounds. The day after victory, Cassius Clay announced in a press conference that he had become Cassius X. The Muhammad Ali bit followed. The new champion won the title in his 20th fight and even he was not in any hurry to fight the dangerous old men of the division. He beat Liston in a rematch 15 months later, then blasted a broken Patterson.

Ali, it has to be said, inherited a safety-first approach from Patterson and took care of a brave Canadian called George Chuvalo, Henry Cooper, London and a German called Karl Mildenberger before fighting two from the list of four great ignored heavyweights. Ali beat Williams, who had been shot by the police, was 33 and was having his 72nd fight, and then Folley, who was ancient at 35 and having his 86th fight. It was better than it had been, but it was hardly a golden period.

It is certainly easier to get to a title now but, as Pricey found out on Saturday night, it can still go horribly wrong.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments