Steve Bunce on Boxing: If there’s to be another heavyweight ‘lost generation’ they will do well to rival the crazy crew of the 1980s

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is a history in boxing of chaos following stability in the heavyweight division and now that Vitali Klitschko has left his title in an attempt to become Ukraine’s president, the greed, secret lobbying and joyful expectation have returned to the sport’s division of kings.

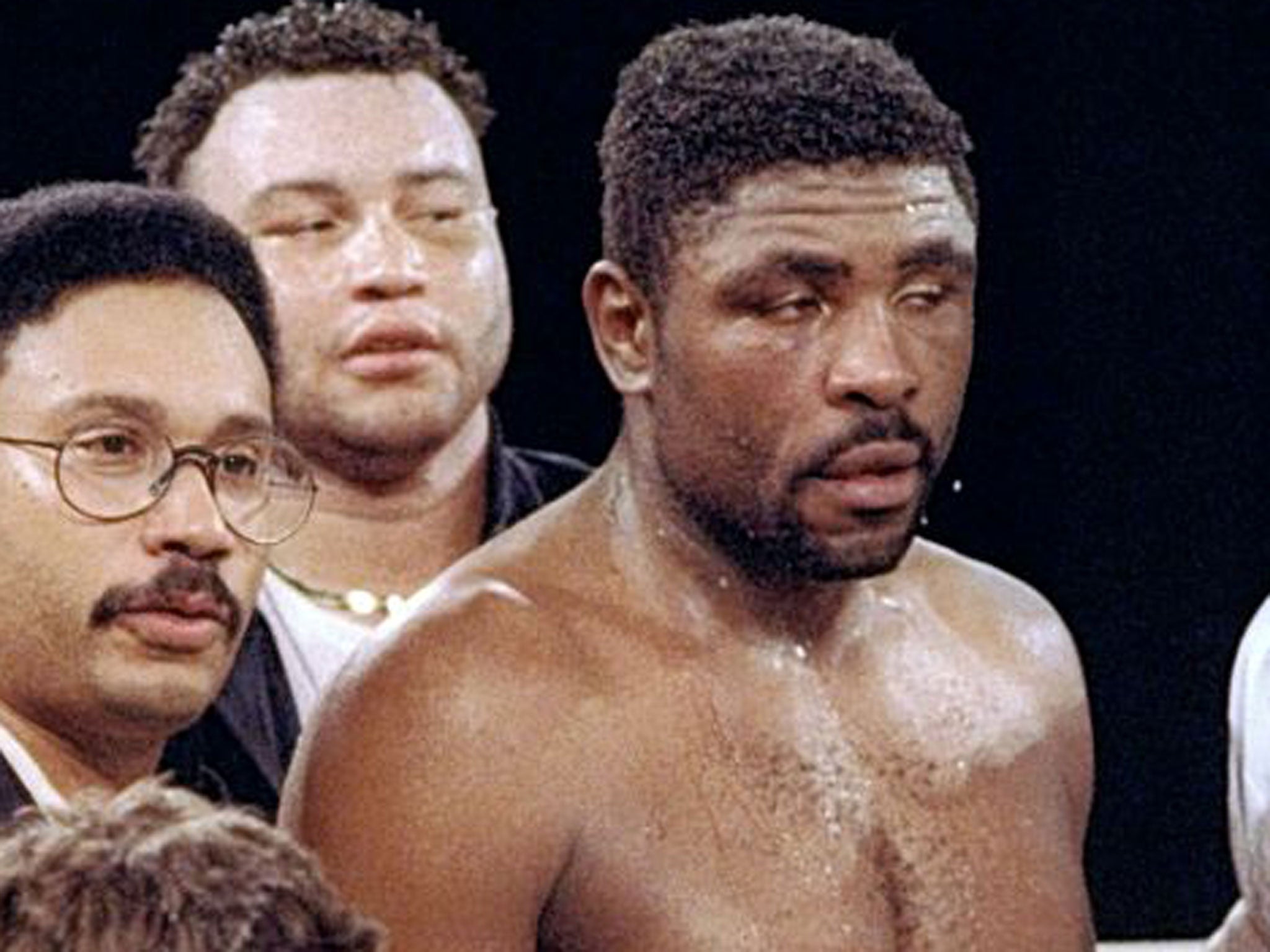

John Tate, Michael Dokes, Greg Page and Trevor Berbick are all dead men from the last time that a lost generation of heavyweight boxers held a version of the world title during a crazy six-year period in the 1980s. It was a time of excess as the good, the bad and the truly ugly went wild on both sides of the ropes.

There were nine other men who swapped punches, crack pipes and world titles between the disgraceful last days of Muhammad Ali and the arrival seven years later of Mike Tyson in 1986. There had never been a time like it, not even when the impossibly glamorous Gene Tunney quit as world champion in 1928 and five champions followed him in five years.

The “lost generation” of heavyweights from the early ’80s were given their name by Tim Witherspoon, one of the more innocent participants in the mayhem, who was still at the very core of the mess but somehow stayed off the crack pipe. He won and lost world titles, failed and was cleared in drug tests, made and spent millions and fell short of reaching his potential.

The first fatal victim was Tate, a fighter of sublime skills and an insatiable appetite for drugs. Tate started 1980 as the WBA champion, having beaten South Africa’s Gerrie Coetzee over 15 rounds in front of 86,000 people in Pretoria; the fight defied sanctions and was in many ways the perfect prelude to the abuses that followed. Tate always regretted fighting in South Africa, had his last fight at York Hall and in 1998 died after a car crash with cocaine in his bloodstream. He had been in and out of prison, on and off rehab programmes and begging on the streets of Knoxville.

Berbick was next on the death list and he quickly fell off the radar and into trouble after his short reign was ended by Tyson in 1986. Berbick had fought his demons on both sides of the ropes and, one night in 2006, he was bludgeoned to death by a relative in Jamaica. It was a brutal ending courtesy of a pipe and a crowbar, and his nephew Harold Berbick and an accomplice, Kenton Gordon, were found guilty of the murder in 2007.

It is possible that Page was the best stylist since Ali to fight in the heavyweight division but he was another of the boxers from the tainted years to hold the title briefly and fade slowly and painfully from the scene. Page won and lost the title in five short months, missed out on the millions and was paid just over $1,000 when he fought his last fight in a Kentucky strip joint in 2001. Page suffered terrible head injuries and was confined to a bed in his Louisville home until the night in 2009 when he tumbled from the adapted bed and was strangled by the very tubes that kept him alive.

Dokes came close to beating the great Cuban Teofilo Stevenson at the Pan-Am Games in 1975 as an amateur and held the world heavyweight title for under a year, which was long enough for him to become the main party animal for the entire “lost generation”. He was, make no mistake, an addict, engaging soul and violent individual.

He served nearly 10 years for a savage attack on a woman he lived with, once smoked heroin in a toilet on a flight to New York for a press conference and became a tragic fixture in Las Vegas, where he asked the boxing tourists for a few bucks whenever a big fight came to town. In the end cancer tore his liver to bits; there were many who hoped it was painful.

Tate, Berbick, Page and Dokes were all better fighters than the dozen or so heavyweights who are poised now to be part of what threatens to be the Lost Generation II. However, the new breed are better men, certainly better businessmen, in many ways, and keep their excesses to rants on Twitter, not six-day benders with fifty grand’s worth of cocaine and a private jet packed with prostitutes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments