Steve Bunce on boxing: Anthony Joshua should follow one golden rule in his pro career - Do the opposite of Audley Harrison

His first fights will be 'knock-over jobs' – and that was good enough for Lewis

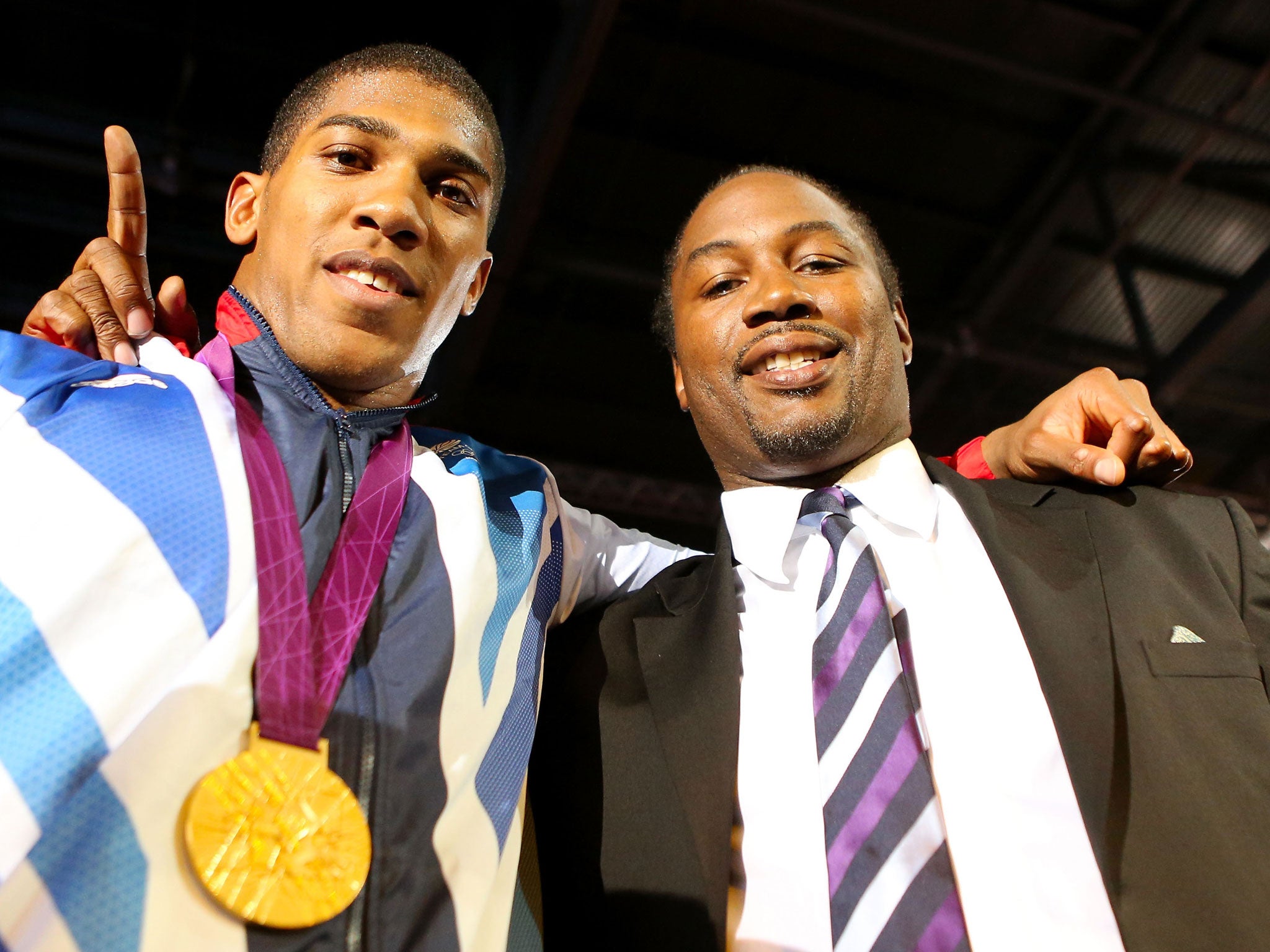

Anthony Joshua should soon discover that his happy days as the smiling gold-medal winner from London 2012 will be under threat when he is knocking over boxers in his new life as a professional far too easily. It is one of sport’s craziest contradictions.

Joshua will box for the first time as a pro on 5 October at the O2 Arena in London and the fight will officially end a lengthy 14-month break from the ring and as many months of speculation regarding his signature.

The last two London-born Olympic super-heavyweight champions, Lennox Lewis and Audley Harrison, each took very different paths from the podium at the Games to the pro ring.

Lewis fought 12 times in 12 months on the road and under the radar, which allowed him to look sloppy and blast some poor opponents without getting any criticism. Lewis, who was 23, the same age as Joshua, stopped 11 of the 12 men, and eight of the fights finished in the first or second round. It is now viewed as a perfect apprenticeship, and the speed and regularity of the contests prepared Lewis for the switch to harder fights.

A decade later Harrison managed to get it dramatically, and in many ways pitifully, wrong when he took control of his early career after doing a direct deal with the BBC. Harrison managed just five fights in 12 months and three of his first six bouts went to points, which was viewed as a power failure. Harrison’s viewing figures plummeted, attendances drifted and a blame game took hold that led to his exile.

Joshua and the men and women in charge of his career, many of whom are virgins in the grubby business of boxing, have to pick a path between the often-anonymous development of Lewis and the high-profile calamities of Harrison’s adventure. Joshua’s rise will be constantly analysed by a boxing public with a very, very short attention span, which was something that Lewis never had to deal with and something that Harrison famously failed to cope with.

As a raw professional Joshua arguably has more to offer than either Harrison or Lewis, which is not the same as saying he is better than either; in boxing it is impossible to predict beyond a dozen hand-picked wins, but the fighter’s attitude is crucial. Joshua lacks the power that helped Lewis develop into the champion he became and thankfully he has none of the arrogance that Harrison exhibited all those years ago. However, he can whack, he has bundles of confidence and his attitude is perfect.

Joshua’s debut will not be as big as Harrison’s grand arrival, when seven million watched on BBC in May 2001, but he is likely to receive as much attention, and some of it could be negative. The Sky publicity machine will be at full throttle when the first victim is selected and that man, who should get a career-high purse, is unlikely to be as comical as Harrison’s debut opponent, Mike Middleton, who was a wonderful fall guy. Middleton, it turned out, worked under cover at Disney World in Florida, often dressing as Mickey Mouse to capture thieves; he lasted just 165 seconds.

The most important thing is that Joshua is not rushed, that he is allowed to work on moves and condition his body to a decade of sacrifice. During the first year his opponents’ poor credentials will only matter if anybody from Team Joshua claims they are a risk. In boxing we call Joshua’s next 10 opponents “knock-over jobs”, and they were good enough for Lewis, Frank Bruno, Mike Tyson, Riddick Bowe and other heavyweights that developed through the regular toppling of men to become heavyweight world champions.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments