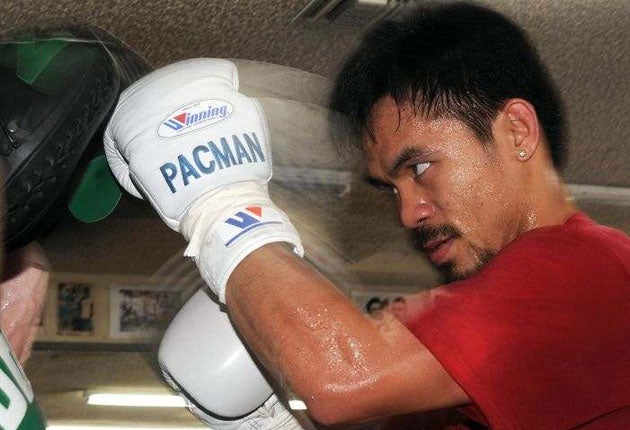

Manny Pacquiao: 'I fight to make my people happy'

He feeds the poor at his home in the Philippines, and took to boxing when his father ate his pet dog. Ahead of his Ricky Hatton bout, James Lawton meets the extraordinary fighter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Around about now, which is to say in the zone of fight time, something happens to Manny Pacquiao that is, if not unique, rare enough to bring a shiver to the spine of a man who won and lost the greatest prize the ring can bestow.

It happens to his eyes and the change is a touch metaphysical.

"I know it when I see it," says Michael Moorer, who beat Evander Holyfield and lost to George Foreman in this city last decade when the world heavyweight title was at stake.

"A look, a light, comes into his eyes which I think you only really understand if you have worked hard and long for a fight," adds Moorer.

"His eyes shine in a way that says, 'This is my time, I can do anything I want.' You do not see it so often but I see it now when I look at Manny Pacquiao. His eyes say, 'Yes, I am ready.' If you are a fighter it is everything you work for. It means you have done everything you had to do, and this is the reward, feeling so good, feeling so alive."

Moorer, always a brooding, introspective figure in a career which also brought him the world light-heavyweight title, is not easily touched by awe, but now, as chief assistant to Pacquiao's trainer, Freddie Roach, who was groomed by the man most acknowledge as the greatest fight guru of them all, the late Eddie Futch, he clearly sees the champion from General Santos City, Philippines, as someone apart.

"Ricky Hatton [who defends his IBO and Ring Magazine junior welterweight titles here on Saturday night] is a good fighter worthy of respect," says Moorer, "but he is fighting someone so far out of the ordinary I just cannot give him any chance.".

Pacquiao's power to draw cultish support has long been a factor in his homeland. There, he is revered as a Robin Hood character, a fighter who moves his people as much by the generosity as the ferocity of his fighting nature. But here this week we have seen the spread of his appeal.

The promoter Bob Arum was so concerned by the fear of hysteria as The Pacman arrived at the Mandalay Bay Hotel and Casino – his favourite local watering hole – that he called off a planned publicity session when a crowd of photographers and fans marched behind their hero through the casino floor.

Roach was grateful for the respite. At the end of last week he cleared his Wild Card gym in Hollywood of the fans – he estimated about 350 of them had crowded into the sweaty workplace – who included the resurrected Oscar nominee – and failed fighter – Mickey Rourke. "The trouble is," says Roach, "Manny loves being loved. He can't say no to anyone."

When he is at home the 30-year-old, who local legend says, turned to fighting as a boy partly out of the grief that came when he was told his father had eaten his dog for dinner, each day opens the door of his house, which he shares with his wife and four children, to a flood of pilgrims. None of them leave empty-handed. He gives them food and money and, perhaps most of all, belief that a little joy and magic can come into the hardest of lives.

Pacquiao had to scuffle on the streets of Manila in his youth – now he insists he will never forget how it is to be poor and touched by a degree of hopelessness.

As a winner of world titles in five different weight divisions, with such scalps as the great Mexicans Marco Antonio Barrera, Erik Morales and Juan Manuel Marquez, and the iconic Oscar de la Hoya, Pacquiao's reputation as a fighter of the first rank has long been secure. But there is something more, and it was seen in San Francisco last week when a great stadium filled with baseball fans, the Giants' AT&T Park, rose up in massive acclaim.

"Manny crosses all borders," says Arum, who so skilfully marketed the young De la Hoya. "He touches everyone with his spirit."

The hero is unabashed when he is told how much he means to so many people. "My main objective," he says, "is to keep the interest of people who love boxing.

"If they love me, too, well, that is good. I want the people to be happy when they watch me fight and I know that it does bring them happiness when I fight well, and so, you know, my wish would be that I could fight every day of my life."

While Roach, somewhat out of character, and Hatton's trainer Floyd Mayweather Snr have been trading insults with increasing intensity, Pacquiao steps to one side. "They can say what they like, it does not affect my focus. This is to prove to the new fans I have after beating Oscar that I am a real fighter, that I have the talent and the discipline to be a great champion. If you want to be great you can never put that to one side."

Some of Pacquiao's zeal goes beyond the reach of Roach's experience. Every two days, reports the trainer, Pacquaio subjects himself to the "Thai stick". "I have nothing do with it because honestly I don't agree with it, but Manny does, so what can I say. An Asian guy works over his body, mostly his forearms and stomach, with a bamboo cane. The theory is that it deadens the nerves when a man is fighting and taking blows."

Roach shakes his head, partly in disbelief, partly in wonderment. If he takes so much of the best of what any trainer could hope for, he seems to be saying, he is obliged to accept the rest.

Mayweather Snr has attacked Roach's credentials, trashed his three awards as Trainer of the Year, disparaged his fighting career – "How would he know about my fighting? He was in prison for drug dealing at the time," was Roach's sharp riposte – but what seems to offend Pacquiao's trainer most is the suggestion that his man lacks power.

"Manny," says Roach, "was knocked out twice as a flyweight many years ago, one occasion he couldn't make the weight. It is not relevant now, because Manny Pacquiao has amazing strength and speed – the power comes from that speed and those legs."

There is also that look which comes into the eyes of the man now saluted as boxing's best pound-for-pound performer. It is appropriate for many reasons, not least that it is owned by a man born on the edge of a volcano who, here for the next few days at least, has reason to believe he has arrived at the centre of the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments