James Lawton: Harrison and Haye take note: Iron Mike had a hundred faults – but he never cheated the public

Tyson's is a lurid story but there was one thing he never did. He never conned the public. He understood fighting, indeed he was a great student of it

It doesn't get any easier to disperse the "fight" anger. But then how can it, when David Haye continues to insult that section of the public which knows boxing?

He might just concede that the joke went too far. Instead, he prefers to stir up the righteous indignation with his dismissal of the already unlikely possibility that the British Board of Control would perform a basic duty and hold back a million-plus purse from his non-combatant opponent, Audley Harrison.

Harrison, says Haye, was always going to go down in the third round. He was simply there to take his beating and how he presented himself for the slaughter was pretty much irrelevant.

This might be all right if we didn't have anything by which to measure the joke of grand larceny always implicit in Haye's so far counterfeit reign as heavyweight champion. This week, however, even the most forgetful of us did.

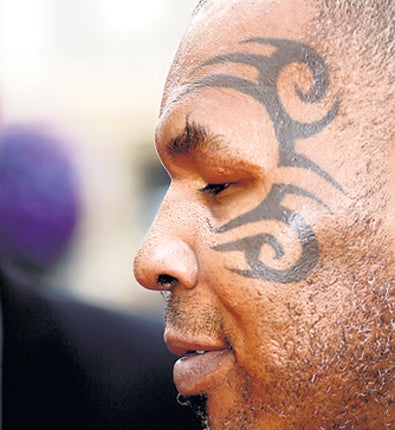

It accompanied Mike Tyson when he came back into our lives in a TV documentary which featured his reading of Oscar Wilde's poignant lament from Reading Gaol.

In many ways Iron Mike was the most appalling representative of what used to be the most prestigious prize in all of sport. You might say that if there is anything to celebrate about his life as he heads into his forties it is chiefly his somewhat miraculous physical survival.

He conveyed the odds against such a development vividly enough when, a few days after he had become the youngest ever world champion with his destruction of Trevor Berbick in Las Vegas 24 years ago, he allowed you to accompany him back to his roots in Brownsville, Brooklyn.

He told a hall full of high-school students of the odds he had beaten to gain the title, how most of his contemporaries were either in prison or dead from drug abuse, and later, when he had returned to Manhattan in his stretch limo with the darkened windows, a young policewoman showed you how it was in the building where Tyson had spent his early boyhood: rats and trash and syringes and human excrement on the stairs and in the apartments, and hopelessness that you could taste.

The Tyson TV show reminded you of all those bizarre days in his company. When he crashed in Tokyo, carousing with death-wish ferocity before being thrashed by the underdog James Buster Douglas; taking flowers to Sonny Liston's grave close to the airport runway in Las Vegas; emerging in the half-light of dawn from the prison outside Indianapolis where he did his time for rape and then serving breakfast to Muhammad Ali in the mosque across the frost-covered fields; the rage when he knew he couldn't beat Evander Holyfield and so why not bite off his ear? And then, near the end, taking you to the hotel room in Louisville where he had installed his beloved racing pigeons and cackling when they defecated on the five-star bed covers.

It is a lurid story, all right, and at least half of it was lived by only a shell of a fighter, who made many of his squandered millions largely on his old bad mystique.

There was one thing, however, that Tyson never did. He never conned the public. He understood fighting, indeed he was a great student of it, and when the time came he knew that there was a price to pay for the dissipation. He took his licks, most painfully when he was beaten by Lennox Lewis in Memphis in 2002. He always knew he had some obligation to put on a show – and make a fight.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments