Gloves come off in the fight for the soul of ice hockey

The NHL faces calls to ice the mayhem after the latest brawl. Rupert Cornwell reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Guess the sport. "Gillies got a good left in there, he staggered him a little bit," enthuses the commentator, "but Godard finally gets a right hand loose for an uppercut – both these guys are willing combatants." Heavyweight boxing? Or some trendy version of all-in fighting? You're nearly right. The correct answer is ice hockey, as practised in the National Hockey League.

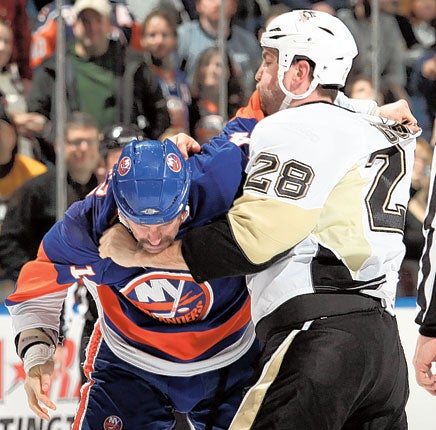

Godard is Eric Godard, a winger for the Pittsburgh Penguins, Gillies is Trevor Gillies, a centre for the New York Islanders. Far more important than their ostensible positions, however, is the fact that both are "enforcers" – the hard men that are a requisite of every NHL franchise, whose real job is to protect colleagues, settle scores and generally dish out GBH as needed.

And both could indeed be heavyweight fighters, each over 6ft 3in and tipping the scales at 16 stone-plus. But on the now infamous night of 11 February, their private set-to (scored, incidentally, as a draw by most analysts) wasn't the main event.

The Penguins and the Islanders have a good deal of previous, to put it mildly. When the teams had met in Pittsburgh six days earlier in a notably bad-tempered encounter, the Pittsburgh goalie skated to centre ice in the final seconds to fell his opposite number with a single left hook.

On 11 February, therefore, there were grudges by the truckful to be settled, and they were. The actual hockey game ended in a 9-3 blowout for the Islanders, but the statistic that really caught the eye was the total of 346 penalty minutes imposed by the NHL on the two teams – not quite a record, but close.

In fact, the Gillies-Godard contest was Queensberry Rules gentlemanly compared with a couple of mass brawls on either side of it. "This is old-time hockey," the commentator noted approvingly amid the mayhem, as the home fans raised the roof. The match officials meanwhile looked on.

This time, however, the tolerant NHL was not pleased. It fined the Islanders $100,000, suspending Godard and Gillies for 10 and nine games respectively. And the episode may not be forgotten lightly. Once again the question is being asked of the NHL, more loudly than ever: is violence in North American professional hockey out of control and a threat to its very future?

Even without the brawls, hockey has always been bruising and sometimes dangerous. It could not be otherwise, with large, heavily muscled athletes careening around an enclosed rink as they fight for a bone-hard slab of rubber travelling at speeds of up to 90 miles an hour.

Like American football, hockey has bred a macho culture. But the Penguins and Islanders stretched that culture to the limit. "Hockey is a tough, physical game, and it always should be," said Mario Lemieux, principal owner of the Penguins and one of the greatest players in NHL history. "But what happened wasn't hockey. It was a travesty. It was painful to watch the game I love turn into a sideshow like that."

To which some hockey fans initially responded: you hypocrite. Lemieux might be a legend, but was he not also the employer of one Matt Cooke, among the most fearsome of NHL enforcers, whose vigilante justice for the Penguins in the earlier game helped stoke the fires of 11 February? More to the point, violence and fights are one of the game's big attractions.

The formula seems to work. After the nadir of the lockout that cost the entire 2004-05 season, hockey has rebounded strongly. Attendances are up, and in 2010-11 revenues are forecast to hit a record $2.9bn.

To those who complain the NHL turns a blind eye to the mayhem, the league's commissioner, Gary Bettman, has a simple answer. "What would happen if we took out a part of the game that has always been there, we just don't know," he said. "But all our research finds that fans understand that it's part of the game, and they don't want to see it removed."

Nowhere is that truer than Canada, where hockey is the national sport. The world sees Canadians as gentle souls but Canadian repressions seem to find outlet in its excessive physicality. Indeed, in hockey's frontier era a century ago, a couple of Canadian players even clubbed an opponent to death with their sticks. Both were charged with manslaughter but both were acquitted – as the defence lawyer argued in one trial: "A manly nation requires manly sports." By contrast, the loudest tut-tutting about rink violence comes from that gunslingers' paradise to the south.

Now, though, it is asked, why is this the only sport where players are allowed to carry out their own justice? After all, if Messrs Godard and Gillies were real boxers, they would expect the referee to enforce the rules. Increasingly, too, people realise that violent sports can exact a terrible price. The NHL faces similar risks to the NFL as a result of head checks of the type more than once seen in the 11 February donnybrook.

And now there is a star exhibit to prove the point – one that may well have inspired Lemieux's outburst. The NHL's current marquee player is the 23-year-old Sidney Crosby, the Penguins forward. Since early January, however, he has not played because of a concussion due to heavy, though not illegal, hits in successive games. The NHL may be on sounder footing these days, but it can't afford to lose the likes of Crosby for long.

Heated exchanges on ice

5 March 2004

Philadelphia Flyers v Ottawa Senators

A four-minute mass brawl earned the teams a record combined 419 penalty minutes. By the end of the game, with 20 players ejected, there was a total of five players left to skate.

16 February 2004

Todd Bertuzzi (Vancouver Canucks) v Steve Moore (Colorado Avalanche)

Bertuzzi had been after Moore all game, and finally connected with a punch to the back of the head which knocked him out. Bertuzzi then fell on to Moore, crushing his face against the ice. Moore had three fractured vertebrae, vertebral ligament damage and a grade three concussion, while Bertuzzi lost $500,000 in earnings as a result of his suspension. It was the end of Moore's career.

26 March 1997

Detroit Red Wings v Colorado Avalanche

The game dubbed "Bloody Wednesday", with both sides seeking revenge from a brawl the previous year, featured a total of nine one-on-one fights, including the opposing goalies Patrick Roy and Mike Vernon squaring up, plus the obligatory bouts of all-in mayhem.

4 February 1994

Marty McSorley (Pittsburgh Penguins)

v Bob Probert (Detroit Red Wings)

The long-anticipated match-up between McSorley and Probert is said to be one of the longest tow-to-toe fights in NHL history. The referees were reluctant to get involved and the players on the bench merely watched as both men slogged it out for over 90 seconds.

Tom Hamilton

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments