Bunce on Boxing: Sykes' bragging offers Brook a cautionary tale

Paul Sykes boasted he would win the British heavyweight title by a knockout in 1979

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

On Saturday in Sheffield, in front of 10,000 punters and a record boxing audience for Sky of just under 500,000 people, Kell Brook reached the stage where bragging and challenging is allowed. It is allowed, but each time a fighter opens his mouth and starts issuing challenges he leaves himself wide open to abuse, ridicule and years of denial. Just ask David Haye, because Brook's verbal assault on Amir Khan was similar to Haye's endless attacks on Wladimir Klitschko.

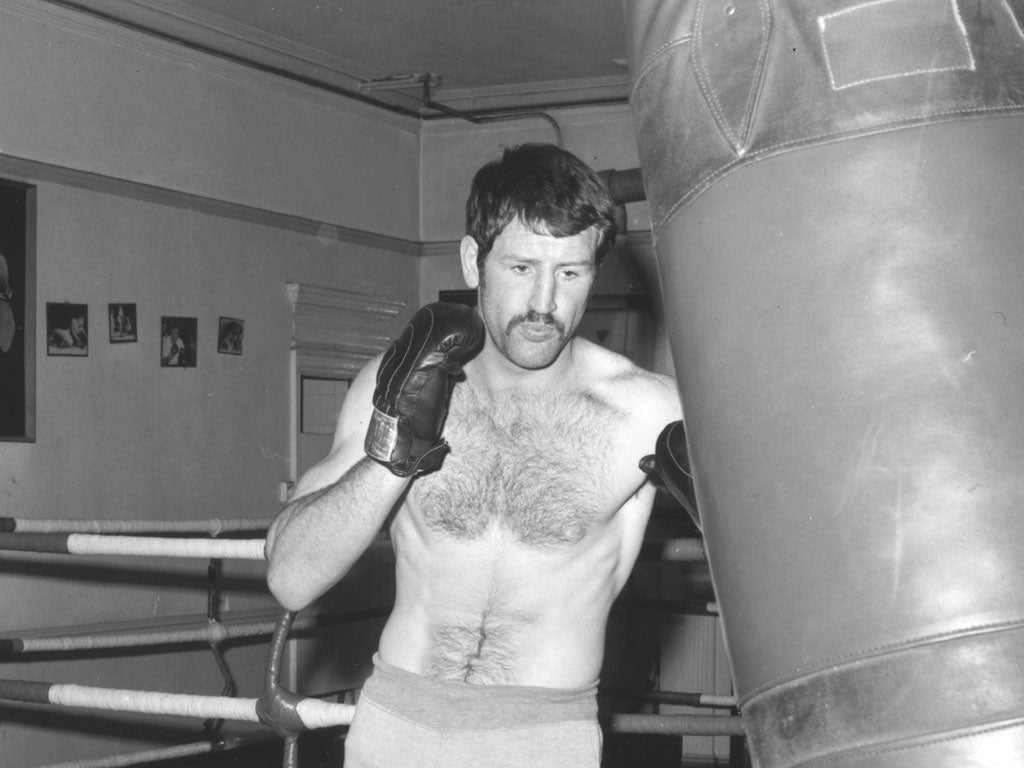

It is likely that the most outrageous challenge to ever become a reality took place in 1976, when a notorious thug called Paul Sykes was part of a documentary about life in Yorkshire's prisons. Trust me when I say that "notorious thug" is a compliment.

Sykes had been in and out of prison for most of his life when the cameras found him lifting weights, swearing at screws and looking down the lens with crazy violence in his eyes and promising to win the British heavyweight title. He was released the following year, when he was 32, and he turned professional with the British heavyweight title, held by Joe Bugner at the time, as his target. The prison interview was shown on TV and the fight, as improbable as it seemed, started to build momentum.

"I'm not a violent man but I am an expert at violence," Sykes said. "I've had an extra 10 years for whacking screws and coppers. I've never hit anybody didn't deserve it." However, tales from the working men's clubs in Wakefield from the rare months that Sykes was on release contradict his claims.

The publicity continued outside the ring and inside the ring Sykes was winning. In his sixth fight he carried on hitting the dazed, confused and then unconscious American David Wilson as he draped helplessly over the ropes. The referee finally dragged a snarling Sykes off.

A month later and a fight with the new British heavyweight champion, John L Gardner, was being talked about. Sykes, it has to be said, did his bit, perhaps realising that his days of freedom were limited. "I will knock him out and then have 750 birds just like Bugner," he said.

They were finally matched at the Empire Pool, Wembley, in June 1979, for the British and Commonwealth heavyweight title. Sykes had won six of his eight fights and Gardner, with Terry Lawless and Mickey Duff guiding his career, had lost once in 30 fights. It was a tricky night: Sykes had a following, a devoted travelling flock of friends and wannabe friends. In the ring it was a savage mismatch as the big daddy of a dozen prison yards was taken apart. The referee needed to halt it long before Sykes turned away in round six. Surrender was tough for an individual who was once dubbed Britain's Hardest Man.

He was soon back in prison and setting records for lifting weights. His life never improved. It was calculated that by 1990, when Sykes was 44, he had spent 21 of 26 years in prisons and had been transferred 25 times. He died in 2007, from liver cirrhosis. He had been living rough at times – in 2000 he was excluded from Wakefield city centre. One of his sons was serving a sentence for murder at the time of his funeral. Sykes remains a tiny footnote in British boxing history but he is also a sobering reminder of what can go wrong when fighters issue bold challenges.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments