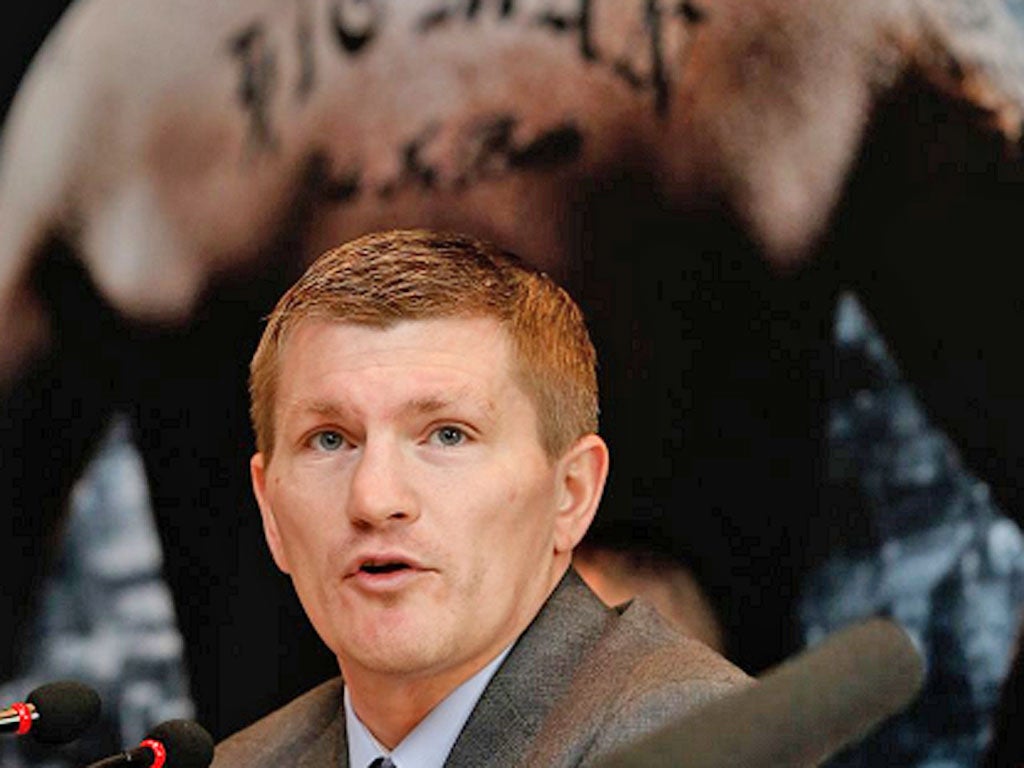

Bunce on Boxing: Ricky Hatton's comeback is not as crazy as some seen down the years

The refusal of Lewis and Calzaghe to fight again is often used as an insult

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nobody in the boxing business is ever shocked when a fighter announces a comeback and there have, trust me, been some idiotic returns over the years.

It is often a bigger shock when a fighter remains on the sidelines, remains retired and, dare I say it, appears to thrive within his inactivity. Lennox Lewis and Joe Calzaghe both quit at the right time, but for some bizarre reason their refusal to be goaded into boxing again is often used as a subtle insult when their careers are discussed. It is crazy because staying retired with money and senses in place should be the objective for all active fighters.

When George Foreman, who quit boxing in 1977, walked from the pulpit of his church in Houston in 1987, to fight in rings in forgotten places against anonymous men, he was on a mission from the Lord. It gently changed from a quest to lose some weight and make enough money to fund some youth projects, to a seemingly impossible dream of winning back the world title.

Foreman first became world champion in 1973 and regained the championship, wearing the same shorts, in 1994 when he was 45 years of age. "I got to the point where I needed to be reminded about things that I forgot," claimed Foreman. "I had two careers, the early one is history and when I watch that fighter on tape I just shake my head."

Foreman returned, made his millions, won the belt and retired again; he was arguably even happier than the first time when his retirement, like his comeback, was preceded by an epiphany following a lacklustre defeat.

There are others that are forced into an early retirement and then, when they are released, begin the most improbable of comebacks after taking a whiff of freedom.

The Tony Ayala Jr tale is a true horror story of failure, violence and a waste of talent. In 1982, Ayala was unbeaten in 22 fights, with 19 knockouts, and he signed for a world title fight. He was also an addict and during a rage he raped a neighbour. He was sentenced to 17 years, served every single day and on release started to fight again. There was no ring redemption for the reformed Ayala and he had lost his edge and quickly vanished.

My favourite comeback involved Ron Lyle, another felon, who as a young man shot a rival gang member. He was released at 29 and a few years later lost to Muhammad Ali in a world title fight. Lyle kept on fighting before retiring in 1980. In 1995, when he was 54 he returned, knocked out four men, but then his body turned on him and he quit before a rematch with Foreman could be made. The pair would have shared a ring and 100 years on earth had the fight actually taken place.

On Saturday in Manchester, in front of a capacity and adoring crowd of nearly 19,000, Ricky Hatton fights again after more than three years away. Nobody, as I said, is surprised by Hatton's return, which unlike so many comebacks in the sport's violent history is not motivated by bankruptcy or a desire to recapture lost glory. Hatton is fighting again to get rid of the demons of defeat that stalk him; his motivation is refreshing, his honesty intact and his personal assessment of the return needs to be brutally frank.

Hatton is certainly not immune to the delights of making a nice few quid, which he will, and winning back a version of the world title, which he is still very capable of doing.

Thankfully, there is no delusion with Hatton's return, no fake hope or stupid claims that this version of Hatton is the best. The version that returns is never better, but the fighter can often be wiser and the fans and the opponents less demanding.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments