Boxing: Sonny Liston was murdered by Mob, claims hitman's son

New book by Greg Swaim about his late father, James John Warjac, claims he helped kill the former World Heavyweight Champion via an enforced heroin overdose

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the world once hypnotised by Muhammad Ali watches the inexorable decline of the most important sportsman of the 20th century with a mixture of admiration, pity and disbelief, compelling evidence has finally emerged about the death of the anti-Ali, Sonny Liston. A tragic mystery now in its fifth decade, it will surprise few that the latest chapter reads like a deleted scene from The Godfather.

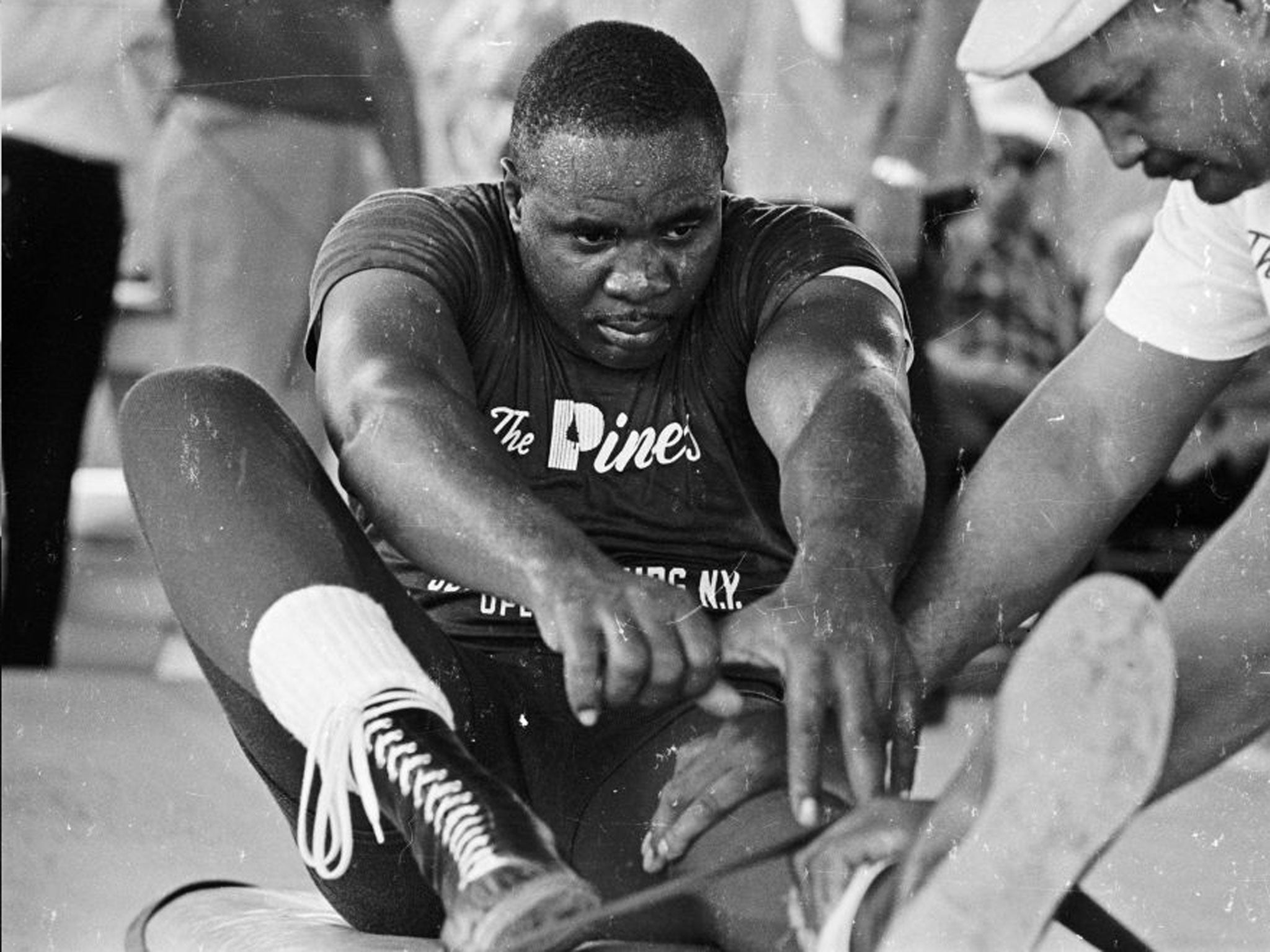

Descents don't come much quicker or crueller than Liston's. If Ali was the face of the civil rights movement, Sonny, as Norman Mailer noted, was "the bad nigger". In 1962 the Mob-managed ex-con with fists like hams captured the world heavyweight title for the Mafia with brutish nonchalance, demolishing Floyd Patterson in two minutes; three years later, in the second of his fruitless and endlessly controversial duels with Ali, a farcical first-round knockout in Lewiston, Maine, extinguished what was left of his credibility.

On 5 January 1970, he was found lying at the foot of his bed in the Las Vegas home where he had spent the loneliest of Christmases. He had been dead for six days. The coroner cited natural causes stemming from lung congestion; Geraldine, Liston's fiercely loyal wife, claimed it was heart failure; nobody else was convinced on either count, not least since one of the victim's arms bore needle tracks.

According to Warjac: Most Wanted, a newly completed book by Greg Swaim about his late father, Dale Cline, aka James John Warjac, the Mob hitman admitted he had helped kill Liston via an enforced heroin overdose, a popular Mob execution technique.

Liston was always destined to meet a sticky end. Feared inside the ring, loathed outside, he needed the aid of gangsters to secure opponents. So long as he was winning he was useful; after Lewiston, he became increasingly dispensable.

Unwilling to ingratiate himself, he did little to help his own cause. For some, the last straw was his alleged refusal to throw a bout with Chuck Wepner, the uncultured bruiser who inspired Sylvester Stallone's Rocky franchise. Liston also knew far too much: who knew what he might he let slip about those Ali bouts? At the time, it was deduced that Liston had fallen while preparing for bed and struck his head on a bench. Police sergeant Gary Beckwith, however, discovered some heroin in a balloon and a syringe near the body. More-over, the autopsy ascertained that Liston's blood contained traces of codeine and morphine – common when heroin is broken down.

Yet as Al Braverman, one his more trustworthy managers, assured me while I was researching my biography of Liston, Sonny Boy, his fear of needles was pathological.

In the early 1980s, when Swaim was 30, his grandmother died, leaving a batch of press clippings about Warjac, who had once been on the FBI's "most wanted" list. Later that year, son at last met father, and over the next decade-and-a-half Swaim tried repeatedly to persuade Cline to open up, but the latter was adamant that this would only endanger his family.

Eventually, during a night of vigorous drinking, the old man relented. He told Swaim about his role in both Liston's death and that of a showgirl who had wed a Texas oilman, depriving his family of a handsome inheritance: another enforced overdose, he claimed. Cline also apprised Swaim of the existence of a movie script that would explain all.

Swaim heeded the warnings, locking away any potentially incriminating material, but his curiosity was aroused anew after he discovered he had a Texan half-sister who shared his yearning for the truth. Together they began working on a book that also links Cline with Robert Kennedy, Frank Sinatra and the notorious über-Mobster Mickey Cohen.

"My father told me the story about Sonny's death – he was there when he was killed, along with others in the Mob," confirms Swaim.

"He was very careful not to disclose too much to me – I assume he was worried about the pressure the Mob may [impose], using his children as a threat."

Those fears were borne out shortly after Cline's death in 1997. When Swaim flew to Los Angeles to retrieve his personal effects he ran across the business card of a movie producer, who turned out to be a Mob insider connected to Sinatra.

"Let it lie," the producer advised. "Too many people are still alive who won't want you to know about this. Your life will be in danger."

The public's addiction to good-fellas and gangster lore remains strong, but even now, as he seeks a publisher, Swaim is probably still taking his life into his hands.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments