Who is Joseph Parker? The boy enamored with boxing who went to Azerbaijan and came back a man

Profile: Parker’s boxing life has taken him from the rich history of Auckland’s Mangere to a secluded, gated-community retreat in Las Vegas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is something ancient and comforting about the Papatoetoe boxing gym in Auckland’s Mangere and the wonders of the pictures on the walls held the attention of a ten-year-old Joseph Parker when he first walked through the door.

A man called Grant Arkell runs the gym, took a young Parker to heart and during the next decade helped to shape the kid that will walk out and fight Anthony Joshua this Saturday in Cardiff under the gaze, expectation and adoration of millions all over the world. “There were so many great fighters on the wall, I knew their names and their faces and then I was training where they had trained,” Parker said.

It was Arkell who put four-thousand dollars in a pot to help send Parker to the Youth World championships in Azerbaijan in 2010 and that meant he could not travel with the boxer; Parker travelled on his own, Arkell asked the Australian coach to help in the corner and Parker, a New Zealand team of one, won a bronze medal.

Parker was born in Auckland but speaks Samoan and has a very close connection to his heritage and the islands his parents left over thirty years ago to start a new life in New Zealand. “My dad was always working, always doing something and I had to go with him from an early age,” said Parker.

He had put the gloves on long before he went to the Papatoetoe boxing gym, had been shown the basics by his father Dempsey, named back in Samoa after the great American heavyweight Jack Dempsey. “My dad had the pads and I used to hit them from an early age,” said Parker. “That was part of growing up, part of becoming a man.”

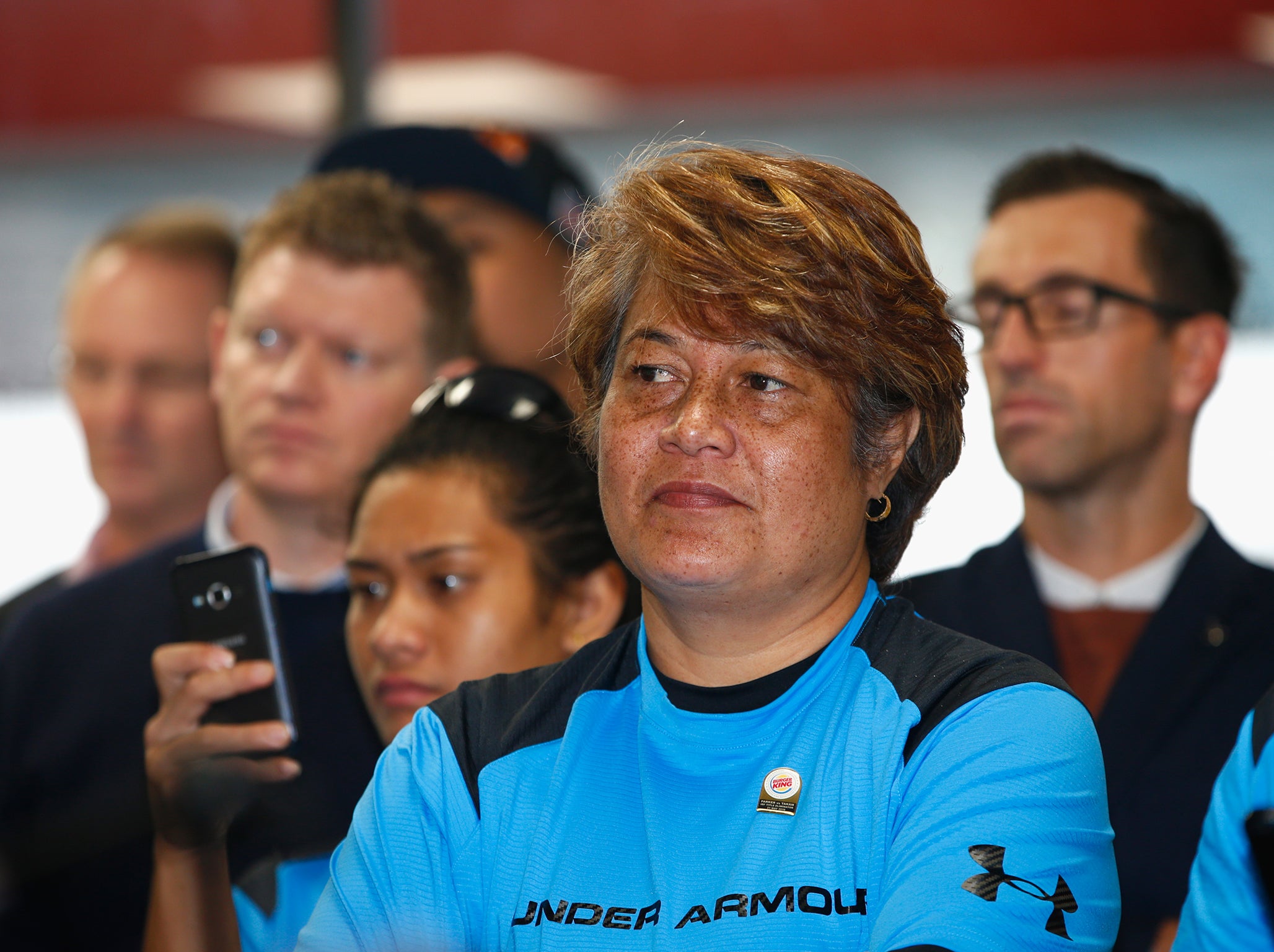

Parker’s mother would then pull him to one side. “She used to tell me: ‘The only time you can fight is when you’re in the ring – it’s a sport and it has rules.’ She wanted it used right,” said Parker. His parents are both here with him for this fight and his mother is the reason he refuses to trash talk. “She will not let me,” said Parker, which is something he shares with Joshua.

“My parents had to make a lot of sacrifices to fund my career,” added Parker. “It was not just flights and my kit, but they had to do everything to help keep me on the road. That is why I always say that I represent my family, my faith and my country when I fight.” Parker is a Mormon.

In 2011 he was back in Azerbaijan at the full world amateur championships and that is where he first met Joshua. “I had watched him early on, I was keeping an eye on him,” remembers Parker. “I lost and I walked to the back of the hall and he was getting ready to fight – I mumbled something, he mumbled something back. It happens all the time.”

Joshua lost in the final, it was the last time he lost a fight.

Parker’s boxing life inevitably took him from the rich history of the Mangere streets to a secluded, gated-community retreat in Las Vegas where he trains with Kevin Barry, an exiled New Zealander who won a silver medal at the 1984 Olympics. The pair are close, the type of relationship that the cynical in the boxing business often sneer at. It works for them and their tiny unit reduces the risk of nuisances trying to bend the ear of the boxer, which is the reason all relationships in the boxing business collapse.

“I guess there are two,” Parker told me last week, still refusing with a smile to refer to himself as Joseph Parker. “There is the one in the gym, locked away, concentrating on nothing more than getting ready to fight. Then there is the other one, the one with the family, the friends, I guess the nicer one.” Parker has a young child, a daughter.

A few years ago Barry took another kid from south Auckland, a hero of Parker’s called David Tua all the way to a world title fight with Lennox Lewis in Las Vegas. Tua lost, Barry was hurt.

“Joseph is not Tua,” insisted Barry, who eventually fell out with Tua. “Joseph is already the world champion.” Tua and Barry were together 12 years, seemingly inseparable and the nastiness of their split is the reason boxing insiders are so cruel about tight fighter-trainer relationships.

In Las Vegas Parker trains, eats, goes to church and helps with household chores as part of his isolation. Barry’s wife Tanya makes the food, Barry makes the rules and Parker and any sparring partners live by the rules and eat the food. It is a stark existence, boring most of the time, but it is what Parker responds to.

The Joshua fight will be his fourth world title fight, he enters the ring unbeaten in 24 fights, with the WBO belt, the blessing of a Samoan nation in prayer and with the hope that one day a kid just like him will walk through the door at the Papatoetoe gym and get inspired by looking at his picture high on the wall.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments