Diego Maradona film director Asif Kapadia: ‘We found half the footage in a trunk in Buenos Aires’

Interview: The new film centres around Maradona’s time at Napoli, where he moved from Barcelona with great fanfare in 1984, dragging them from relative obscurity to championship winners

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

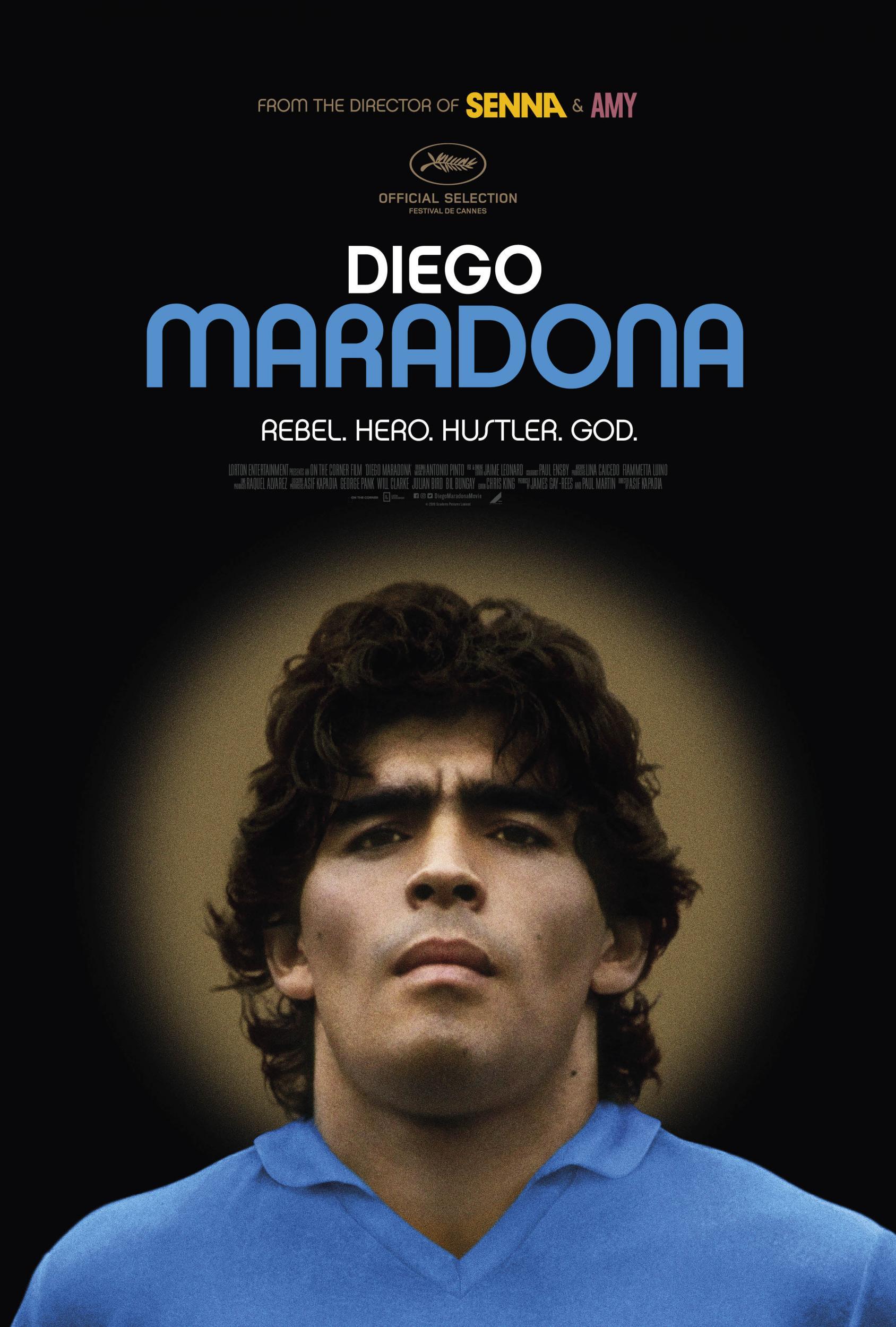

Your support makes all the difference.Ahead of the release of Diego Maradona, the film’s director Asif Kapadia, who also directed Oscar-winning Amy and Bafta-winning Senna, sat down with The Independent to discuss making the movie, gathering the extraordinary footage of the World Cup winner in his prime, and meeting the man himself.

The film centres around Maradona’s time at Napoli, where he moved from Barcelona with great fanfare in the 1984, dragging them from relative obscurity to championship winners in one of the fiercest league’s in European football.

His talent intertwined with the most dysfunctional city in Europe to create a wild story both on and off the field, in a relationship which grew more and more conflicted.

Here is an excerpt from our meeting with Kapadia. To listen to the full interview, download The Indy Football Podcast on Monday.

Jonathan Liew: Are you proud of the film?

Asif Kapadia: Yeah. It’s a weird one: I make these films and now I’m waiting for the response, so there’s a little moment of ‘what do people think?’ You’re handing it over. But I think he’s such a challenging character, such a tricky person to deal with, in a way making a film about him and trying in any way to tie it together is an achievement in itself. I’m open... what did you think?

JL: I really enjoyed the film. I thought it was a tough watch, at times, in common with Senna and Amy, there were parts where it felt unbearably sad, but I do think you get an insight into his character that you haven’t often got from a lot of the books or even the football coverage. What do you think you were setting out to achieve when you started out on this project?

AK: It’s had quite a long journey, because I read a book about him in the late 90s when I was just starting as a student, and I remember thinking wow, what a life. I had no idea where he’d come from or what he’d been through, the amazing things he’d achieved on the pitch but also just the chaos off the pitch. He puts himself in situations and everything’s calm, he’ll create and argument or a fight. So I think that was interesting, and it was 98 or 99 when I read this book and I remember thinking wouldn’t it be great one day to make a film about Maradona, but at the time I was just making short fiction films, I’d never made a doc. So this kind of project came and went and came and went a few times, and by the time it came around again post-Amy, it was like, well I’ve made these two films about these two brilliant geniuses who died really young, so if I going to do a third one it needs to be different, and actually, what happens when you get old? What happens when you lose the gift you had, you lose your talents, you have to deal with some of the mistakes you’ve made in your life? How do you deal with growing up? So I thought that was one of the challenges that interested me in him and his character.

But then he’s impossible to nail down because he just keeps going, whenever you think you’ve got an ending, something else will come along. You think OK, maybe it’s this and then he’ll do something else and something else. I’ve met his biographers and journalists who followed him for decades, and they said ‘good luck’. That became my question when we were making the film – so where do you think this story ends? – and they were just laughing because you can’t do it. Every time you send a book to your publisher, he will do something next week which makes the last chapters irrelevant. So that was a challenge. How do we end this? How do we do it in such a way where we give it an ending but also leave it open? Because he will do something, as he does continually, that throws everything up in the air.

So Naples became the centrepiece because it definitely felt like to me there was a before and after. He arrives as one person, a vulnerable innocent kid, and he leaves as someone very different. And during that seven-year period, he becomes the best player in the world and wins the World Cup in what everyone says is the best case of a single player taking a team through. He wins a championship in Italy when it was the most difficult championship, and I don’t there’s ever been any title that’s ever been as difficult as winning a title in those days, in Italy, with a club that’s never won. It’s also the character of Naples and its relationship with him, and everything that comes with Naples in the 80s. So it felt like that was the story, and everything that comes after is a repeated cycle of Naples, and everything before it was a minor cycle: of him arriving, great hope, he does something brilliant, something goes wrong, he gets into an argument, they don’t want him anymore, he goes, he’s dead, it’s over, and ah, he’s made a comeback. So death and resurrection is the way his biographer, [Daniel] Arcucci, described it, and that’s what it is, a series of cycles of death and resurrection and hope, but the biggest one was always going to be Napoli, so that’s the movie.

JL: As ever, the archival footage is breathtaking. Where does it come from, how did you obtain it, and what was the process of sifting through all of it trying to make your movie?

AK: So this was the beginning of thinking, OK there’s a movie in this. This producer, Paul Martin, contacted me around the time of the London Olympics and said there’s this archive of Maradona private footage, I think I can access it. This was just after I’d made Senna. I had a look at about 10 or 15 minutes of it and I though this is really interesting, but I’d just done this film about the Brazilian hero and I thought I can’t go straight into a film about an Argentinian hero. The timing wasn’t right. But I introduced Paul to James Gay-Rees who produced Senna and Amy, and they went off to somewhere like an hour outside of Naples to this guy who had lots of tapes. They saw some of it and they thought this could be really interesting, it’s all private footage shot for Diego. Then they contacted Diego’s lawyer and tried to do a deal, which they did, and it was only after that that I got involved.

There were Diego’s first agent, was Jorge Cyterszpiler, do you know this guy? Big curly hair and he walked with a limp. He knew Diego when they were kids, they kind of grew up together, and he came for a more middle-class, educated background. He’s a really fascinating character which we just didn’t have time to get into in this story. They were mates from when he was a youth team player. Jorge essentially did the deal to get him to Argentinos Juniors, he did the deal to get him to Boca, he did the biggest deal ever to get him to Barcelona, and he did the biggest deal ever again to get him to Napoli – so he’s the first super agent. He had one client, Maradona, he did the two biggest deals in the world. But he also had this idea in 1981: Maradona is a star, so he did a deal with Puma which he still has now, he did a deal with Coke, and he says we should make a feature film about Diego Maradona. So he hired two Argentinian cameramen to follow Diego around, on the pitch and off the pitch, and they shot in those old format called pneumatic, which is a very 80s format, and that’s what we’ve got access to.

The film started shooting in 1981, it was never made. When his leg gets broken, the whole operation has been filmed, his wife giving birth, so these guys have access all areas. These takes end up with the cameramen, but they can’t use them because they don’t have his permission. We can only use it because we have his permission and his image rights, but then part of the deal was we have access to your private footage and archives and photographs, and you have to give us permission to talk to everyone in your circle. So that’s how it came about. Hundreds of hours are filmed by these two Argentinian cameraman, half of it was in Naples, we found the other half in a trunk in Buenos Aires in the backroom of Diego Maradona’s ex-wife Claudia. It hadn’t been touched for 30 years. We had to bring a machine over from the UK, massive machine, about half the size of that table, and lug it over there, and the tapes were disintegrating, and I said to Claudia if you don’t want to do a deal with us, this footage is going to vanish forever, let me just digitise it and we’ll give it back you as a digital fileset. It was long after that we were able to actually get a deal to access it and use it, so a lot of the footage came from there.

That’s not just off the pitch; when he’s on the pitch playing and we have a close-up of Diego, that’s because his own cameramen were allowed on the pitch to shoot it, because back in the 80s, Italian football had a high angle shot from the top of the stand, they had a few cameras but it’s not like now where you have 50 cameras, so those shots even when he hasn’t got the ball they are looking at him, that’s because they were his guys. they can be right behind the goal, in the changing rooms, in the tunnel, when he arrives and he has that gladiator shot and he’s walking into sign for Naples, they’re in the car with him, so all of that material came from his own private cameramen. When I interviewed people everyone had their own private footage, photographs, this is pre-phones so there wasn’t a lot of that but there were home movies like the ones Claudia had, news footage, French TV.

JL: At what point do you slip that into conversation – ‘have you got any camera footage’?

AK: All of the material that comes in from the archive producers, I then look at it and go through it. But part of it is looking at Diego, because at the time when it arrives it doesn’t have a date on it, so you have to look at it and guess what period it’s from, what part of his life. I’m looking at him and studying his face and his eyes. He looks happy here, he looks unhappy here, what’s gone on here? Then you question ‘who’s that bloke next to him?’ Later on you go ‘oh that’s his trainer’. So let’s go speak to him. You interview him, explain what you’re doing.

I interviewed the trainer and asked him if he’s got any pictures. He said he had a few photographs. So it normally comes after knowing who they are, talking to them, pitching the idea to them, then saying is Diego on board. Then I’ll try and meet with people and ask if they’ve got anything. Most will say no but this process is like making a mosaic. You find lots of little pieces of broken glass and you put them together, step back and you have this picture. No matter how small, you don’t know how useful it’ll be. Someone will have a record of something.

JL: How do you organise that all? Do you have a big wall, a timeline?

AK: Depends on what space you have. With Amy we had a massive office so we did a timeline of her life. Every event that happened a piece of paper was cut out and put on the wall. You get a visual representation of someone’s life that way.

With Diego, I just didn’t have the space as we moved offices. But there was an element of that which I always do. With Diego, it was more of a whiteboard, so I’ll draw a graph with key dates and moments in his life and, using that arc, highlight when he was playing for this team. This was when he went to the World Cup, this is when he won the Scudetto. This is when he breaks his leg. This is when he gets divorced, this is when his kids are born. This is when the kid he doesn’t recognise is born. Initially I thought I’m not interested in tabloid stuff, not going to go there. But more and more when you dig up stuff, when I’m doing my research, you realise that seemed to be a really big thing. I didn’t think that was going to be a part of the story, I didn’t think I’d want to go into that, I’m not interested, but actually that was the turning point.

JL: At what point did you bring Diego into the process?

AK: The producers’ original deal was access to him, access to his image rights, access to people around him and his family and friends, but also the footage. But the deal was three interviews of three hours length, so that was the deal contractually.

JL: That’s not a huge amount?

I don’t know where that number came from. I wasn’t there for the initial meeting. My feeling is they say three but I’ll get seven. I always feel I’ll get more. Once people get engaged they talk more. Diego was tricky in the sense of getting to him. We were in London, he was living in Dubai at the time. Just getting to Dubai is expensive and hard. The first meeting we were there for nearly a week. Every day there was a reason why he wasn’t able to meet and it was cancelled to the next day and the next day and the next day. There was a bunch of us there. It was costing a lot of money. Eventually I met him for five minutes. I said ‘Hello’, he said we were going to make a great film. ‘OK. Bye!’

So I thought the only way I’m going to be able to do this is treating it like Amy and Senna where I haven’t got the lead character. I just have to make the film. But once I have the film I’ll ask him specific questions, so it wasn’t a do the interview first, make the film. It was make the film then talk to him.

The next time we went along it was better but he was quite tired and not particularly well. Slightly slurry. I thought this was going to be hard as I’m not understanding what he’s saying and we probably had about an hour and a half with him, and then his energy level dropped off. So I thought I was never going to get three hours. So I asked if I could come back tomorrow and the next day he was better, he was actually engaged, sharper, enjoying the process. We got a couple of hours with him and then again, his energy dropped off suddenly. So overall, we had around three hours each time we went out to see him, with six or so months in between when we were editing back in London.

JL: How much of an impression did you get he knew what was going on?

AK: Until they see the film, sometimes they don’t get what’s going on. He hasn’t seen the film yet. I doubt he remembers me either. He sees so many people per month, why would I be any different to the interviews he does every week?

There was an element that he’s also done so many interviews from an early age, dealing with press from the age of 15, 16, so I’ll ask him one thing and he’ll give me a great story about Sepp Blatter, for example, and I know and he knows that for a lot of journalists they’d be like ‘wow, what a headline’. And journalists have said he’s brilliant, you’re always going to get your quote, but that’s not what I need.

So I’ll come back again to the original question and he’ll say I don’t want to talk about her. OK, what about this guy? Oh he stole from me! So you’re like, how do I get to the heavy bits? Eventually it was the last interview, I knew I had to talk about these things and by then we’d worked out the technical process well enough because he doesn’t like being held waiting. If I originally went with one translator, I’d speak in English, she’d translate to Spanish, he’d answer, she’d translate to me. He didn’t like the waiting while I was being given an answer. So we had to come up with a way to do live translation. By the time we got to the final interview, Diego was sitting on his sofa, there’s the translator, she translates my question to him, he answers, but I had a Neapolitan sound recordist that I met while working in Naples there. So he [Diego] loved Luka because Luka was there, watching him, he was a season-ticket holder, he was watching him when they were playing. So they got on along and could talk about the good days in Naples. Then I had my laptop which was on FaceTime to my team in London who were typing if there were inaccuracies or anything that I wasn’t sure about. Fact checking, basically. I could type it and they would give me an answer in text. I had a phone dialled to Buenos Aires where one of our brilliant researchers, who understands Diego’s Spanish, was listening to his answers and calling me on another phone so she could do a live translation.

So we were in Dubai, there were people listening in London, there was someone from Naples and someone in Buenos Aires all at the same time so I could have a direct conversation with Diego and he could answer. Importantly, if he gave an answer that was going to be 10 minutes about something else I could interrupt him as I know I’ve only got an hour and 30 minutes. So you’d cut him and say ‘No, that’s not my question’, and you could see he wasn’t used to that.

JL: What did he get most engaged about?

AK: He did like talking about his family, his parents, his upbringing. That was quite powerful, and also the fact of not really contemplating where he was going to end up, this idea of becoming successful and feeling quite lonely, not having anyone around him. Partly that’s kind of the ego of getting to the top – and when I get to the top I’m on my own, there’s no one around me. But it’s also the whole support system. There’s no advice. That was quite emotional. He remembers all the England game. He spoke about that. He was quite open in the first meeting too. He said I’m happy to talk about drugs, my addictions... I want to make something that will help the kids.”

Diego Maradona is in cinemas from 14 June.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments