World Cup 2018: Clive Tyldesley on racism, Twitter vultures, finding the right words and a last Champions League final

The ITV commentator tells Jonathan Liew why finding the perfect way to describe the moment - be it Poland vs Senegal or the World Cup final - can prove the be all and end all in his industry

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

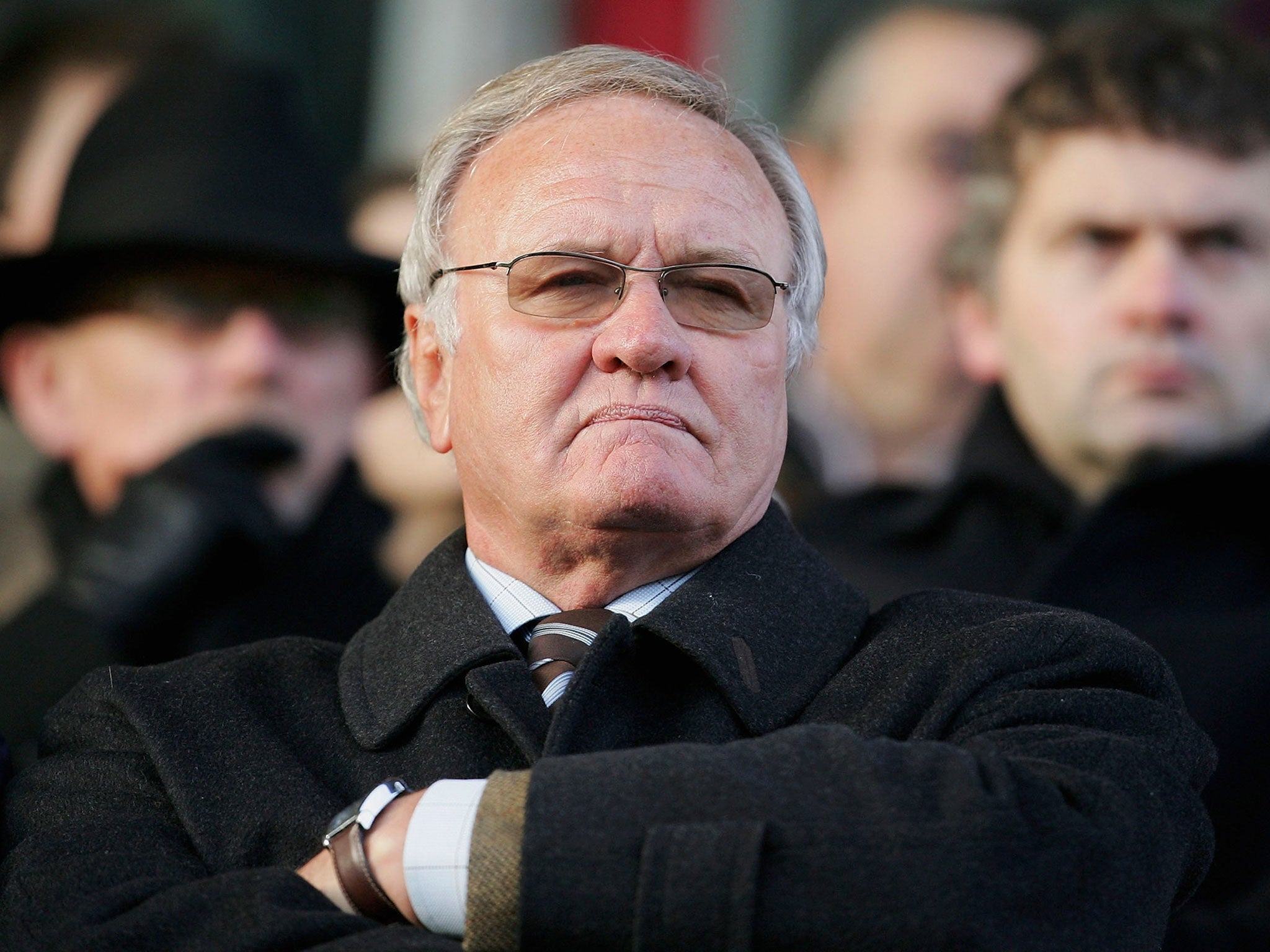

There is an exquisite moment in most Clive Tyldesley commentaries when, quite abruptly and quite imperceptibly, for just a fraction of a second, he leaves us hanging. He pauses, waits, lingers on the brink of the letter just a sliver longer than he needs to. Like a double space in written text, you’d barely notice it. But you can hear it, in: “Remember the name - Wayne Rooney!” Or: “And Solskjaer has won it!”

There’s probably a word for that minuscule pause. Tyldesley would probably find it.

“I’m always looking for the right word,” he reflects over a plate of salmon and a glass of wine in a central London restaurant. It’s five days after the Champions League final between Liverpool and Real Madrid, and although the World Cup is ostensibly the topic for discussion, the memories of a vivid and poignant night in Kiev are still uppermost in the mind. “When Gareth Bale scored his overhead kick, I think I said: ‘Stunning!’ It wasn’t ‘brilliant’, because he had no right to try it. There was a surprise element.”

He’s pleased with how it went: his 20th, and probably last, Champions League final as a commentator. ITV lost the live rights in 2015, this was its last year of showing highlights, Tyldesley is 63 years old, and he’s wise enough to know that’s probably his lot. “But,” he insists, “I have no intention of retiring. As long as I can still see. And as I long as I don’t fall into judgmental traps about footballers spitting.”

And to his credit, Tyldesley has never really been an ‘in-my-day’ commentator, despite his relatively advanced years, and the fact that his day – covering Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest in the 1970s and the all-conquering Liverpool’s side of the 1980s for local radio – was actually fairly spectacular. Very occasionally, he admits, he will indulge his censorious side. “When I got the replay of Sergio Ramos getting Sadio Mane booked on Saturday,” he remembers, “I just said: ‘Embarrassing’. Twice. Now, that’s a bit Barry Davies.”

For the most part, however, he’s determined to remain current and relevant. Over the course of a breezy hour, during which he's as comfortable talking about Twitter storms and the rise of e-sports as he is discussing his early days at Radio City on Merseyside, it's clear that what time has given him is a certain perspective.

“The whole Raheem Sterling thing this week,” he says by way of example. “When I first saw the tattoo, I was as appalled as I am by a lot of lyrics in rap music, that glorify drive-bys, ‘pop it like it’s hot’, all that stuff. And I like rap music. But as soon as there’s an explanation attached to it, that’s OK. I’m a little disturbed about the whole role model thing. Is Jay-Z a role model? At what point does a footballer take on the responsibility of a church leader or a politician or a parent? My dad was a huge Frank Sinatra fan, but I never had any leanings towards organised crime.”

For Tyldesley, the gradual migration of football from terrestrial to pay-television, the gradual evolution of footballer from local hero to global god, the gradual hardening of the border between the game itself and those who watch it, has repercussions that will eventually be felt. “The trust between ourselves and the game is totally broken down,” he says. “The marginalisation of football, in terms of the numbers who can now see it on television, is creating a generation that can take it or leave it. Football has taken its public for granted for generations. You could almost write an Orwellian novel about the day that football suddenly realises nobody wants to watch any more.”

On a more practical level, the widening gulf between players and the media has made his own job a lot harder. With England, Gareth Southgate – a former ITV colleague and guest at his second wedding a few years ago – will frequently give him a heads-up on the likely starting XI. But the days when Tyldesley would have a “snout” in the dressing room of every Premier League club, passing on team news to help him out with his commentaries – are long gone.

He remembers a game he was covering for Match of the Day in the early 1990s, between Howard Wilkinson’s Leeds and George Graham’s Arsenal at Elland Road. He had tried calling Graham for team news, and got nowhere. Next, he phoned David Rocastle at Leeds. Rocastle gave him the lowdown on the Leeds team, before dropping a bombshell that had evidently come from his own source in the Arsenal dressing room.

“You know Alan Smith’s not playing, don’t you?” he asked. “He’s got an injury. He’s not travelled.”

Tyldesley takes up the story. “So I drive up to the Holiday Inn in Leeds, and quite accidentally, it’s the same hotel the Arsenal team are staying in. About one in the morning, the fire alarm goes. So we all trudge into the car park, and George Graham walks over: ‘Hi, how you doing?’ I said: ‘I don’t want to worry you, George, but I can’t see Alan Smith anywhere.’

"He looked at me, and said: ‘You bastard’.”

The access may not quite be what it was, but Tyldesley still yields to nobody when it comes to preparation. He’s doing the opening game of the World Cup, Russia vs Saudi Arabia, and the opening ceremony that precedes it – “half an hour of men on stilts,” he says. And despite the fact that few of his viewers will know or care about the 46 players in the Russian and Saudi Arabian squads, Tyldesley will be as thorough as he has always been.

“Mark Clattenburg has been quite helpful in putting me in touch with a good Saudi journalist,” he says. “I’ve got a guy in Russia who’s pretty good. You’re basically going through two layers of research. On the one hand, you owe it to your profession, and the participants, to be accurate in identifying players. And the second aspect is what I was taught from my very early days: what’s the story?

“You editorialise. The art of good commentary is to present what’s important, and leave out what’s not. The reason we’re allowed to go to a football match for free and sit on the halfway line is essentially so we can send back the message from the front. Pheidippides was the first journalist. We are sent down to the Battle of Marathon because we have the capacity to run back and tell everybody who won.”

It’s flourishes like these – a formidable intellect, worn lightly – that has occasionally opened Tyldesley to criticism over the years. For some he’s irredeemably pompous, for some indelibly biased, for others – usually nameless eggs on Twitter – he’s the source of pure, monstrous evil. Such is the inevitable lot of the public figure in the social media age, of course, and when it comes to the abuse, commentators seem to get it worse than most.

“Twitter is not an opinion poll,” he reminds us. “It’s a soapbox for whoever shouts loudest. My @-mentions for all the other hours I live on this planet are pretty idle. Then, for 90 minutes, they are stirred into all kinds of views and verbosity that my wife will monitor on my behalf.

“I don’t mind the haters. My work is a matter of opinion. The ones I hate are what I call the vultures. And the problem with Twitter is that the wildfire starts, and within 10 minutes the original debate has passed. It’s become a matter of fact that what you said was inflammatory, or racist.

“I used to play a game when Top Gear was in its pomp: how long until Jeremy Clarkson said something that would end my career? It was usually about eight or nine minutes. The same box in the corner of the room, the same time slot. Neither of us in positions we’ve been elected to. And yet: I’ve got some moral responsibility that he hasn’t?

“Here’s the other thing: the apology is dead. We have become totally unforgiving. I don’t particularly want to stray into political areas – I’m no longer a member of the Labour Party, but I’ve been a voter all my life – but I’ve seen good politicians, capable people, lose their jobs over totally nothing. Simply because of what I call Daily Mail morals.”

Then he adds, quite abruptly: “Ron was different. We all got that.”

Almost as if anticipating the subsequent counterpoint, Tyldesley now addresses the Ron Atkinson incident. It is 14 years since Atkinson, at the time a respected ex-manager and broadcaster, lost his job at ITV, quite correctly, for using the N-word during a Champions League broadcast when he thought the microphone was off. Tyldesley was sitting next to him, and saw the implosion of his friend’s career in real time. Atkinson, quite correctly, hasn’t worked in commentary since.

“I wasn’t really aware of what he’d said, to be honest,” he remembers. “The studio were talking, I was half-listening to them, and he was still ranting away. It was probably the first and only time I’d heard him say n****r. He’d make jokes that... he might have to laugh at himself. But then, he made jokes that we all laughed at. I think it was a generational thing. While his language let him down, his heart and soul were always in the right place.”

And for Tyldesley, it ultimately comes down to language. Choose the right words, in the right moment, with just the right length of pause in between them, and the heart and soul will take of themselves. “The language is there to be emotive,” he says. “My wife and I saw Elbow at the NEC a couple of months ago. Now, Guy Garvey can write lyrics about love that bring tears to my eyes. ‘We kissed like we invented it’. Nobody has ever written lyrics as good as that. It’s popular art, and it’s brilliance.

“Now, I’m going to take a big swing here, but I am in popular art. And if ‘stunning’ is the word to describe Gareth Bale’s goal – and I still think it is, five days later – that’s good work. It didn’t make anybody cry, but I challenge anybody to find me a better, usable word to describe that moment. That’s when I feel good about my work. And that’s when I become reinforced against the haters – who are fine – and the vultures, who will say: ‘Is he referring to the use of stun guns?’”

Tyldesley knows, of course, that the idea of the humble football commentator as lyricist, wordsmith, orator, is one apt to generate its own quantum of ridicule. There are doubtless those who will snigger at the notion of elevating the seemingly prosaic function of reciting footballers' names on television to the level of performance art. But then again: if he’s not going to take his craft seriously, who else will?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments