How a World Cup qualifier and the suicide of a young girl launched the bloody 100 Hour Football War

El Salvador vs Honduras in 1969 left an 11-year mark on the country which is still felt today

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

This is a story of a football match, a martyr with a bullet in her heart, two teams at war and a despot slain by a bazooka in a truly desperate struggle to reach the World Cup in 1970.

In early June of 1969 the El Salvador national team travelled across their disputed border for a World Cup qualifier against their neighbours, Honduras. The night before the match the calm was invaded when bricks were thrown through the windows at the hotel in Tegucigalpa where the El Salvador team had been housed. Not pleasant, not a tragedy and not unusual.

In the match, Roberto ‘The Pistol’ Cardona scored the late, late winner for Honduras to win 1-0; they were closer to Mexico and the World Cup of 1970. It was, as expected, a dirty affair, nasty, cynical and with the threat of real violence in the air.

However, in El Salvador on that fateful Sunday night, watching on a tiny crackling black and white screen, a girl called Amelia Bolanios, a football-mad teenager of just 18, left the room after the last-minute goal from The Pistol and grabbed her father’s gun from under his bed. Bolanios pointed the barrel at her broken heart and fired. She died instantly.

The newspaper, El Nacional, reported her death on the front page, part of the lurid coverage of the shameful defeat against their hated neighbours. “The young girl could not bear to see her fatherland brought to its knees,” the editorial noted. The whole country was instantly mourning for the dead teenage girl. Meanwhile, the team returned and the authorities had to prepare for the second leg, in El Salvador, just seven days later in San Salvador and the funeral; there was no sense of calm in the towns and villages of El Salvador and it said the “death birds” circled high above the stadium.

The national team walked with the coffin carrying sweet Amelia through the streets during a national day of mourning. The president and his henchmen cried their tears and held up pictures of the dead girl during the nationally televised event. As Bolanios was buried, the second leg was still a fixture and that is staggering. Her final picture was on the pages of the papers on the day of the match, with one headline declaring: “She couldn’t take the shame.”

In San Salvador, the night before the match, the Honduran team hotel was wrecked, pigs’ heads were thrown through the windows. On the day of the match the First Mechanised Division of the El Salvador army transported the Honduran players to the stadium in the backs of tanks. “It looked like the soldiers wanted to kill us, shoot us there and then,” said Mario Griffin, the Honduran coach. The route was lined with thousands of people holding up pictures of the dead girl and the crack National Guard handled the Honduran players and officials like they were captives, frightened men being shuttled to an eager firing squad. Inside the stadium the Honduran flag was burned, replaced by an old rag and under this canopy of death and hate the match was played. It finished 3-0 to El Salvador.

And then people started to die.

On the way out of El Salvador two Honduran fans were butchered, hundreds finished the night in hospital with machete wounds and 150 cars were left ruined as the border closed. “It’s lucky we lost,” offered Griffin. The Honduran authorities complained and a third match was ordered, this time in Mexico at the end of the June. El Salvador won 3-2 and booked a place at the World Cup.

Meanwhile, the tension on the border, a notoriously violent border, increased in the days after the second game and it remained closed. Both governments made bold claims of covert slaughter by opposition guerrillas in the border lands and then in early July a proper war started. It lasted for 100 days, 6,000 died, 12,000 were wounded and 50,000 people lost their homes. A truly legendary Polish journalist called Ryszard Kapuscinski went to cover it and dubbed it the Soccer War. He knew football was at the dark heart of the violence.

The combined armies of El Salvador attacked on two fronts, the North Theatre and the East Theatre, and their air force converted C-47 passenger planes for bombing raids on the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa. The Honduran air force struck back. It is a war for war buffs because ancient planes from the Second World War, flown by veteran American pilots, were used in action for the last time; men flew F4U Corsairs and P-51 Mustangs on bombing and strafing raids as the death toll mounted and the bloody days ticked away. There were dogfights, American planes against American planes, above the green hills of the border. Both sides were reduced to machete fighting when ammo started to run short; the Hondurans had the help of Anastazio Somoza Debayle, the Nicaraguan leader and noted despot in a time of despots. Debayle would eventually die in a 1980 raid by a Sandinista death squad - given the name Reptile in honour of his nickname - when he took the full force of a single bazooka one night in Paraguay after an earlier exile in Miami.

It took 100 hours before something like peace was restored after Honduras made countless international appeals. However, a final peace treaty between the two countries was not signed until 1980.

Each year the death of Amelia Bolanios is celebrated in El Salvador. And each year the 6,000 dead are mourned on either side of the sad and unforgiving border.

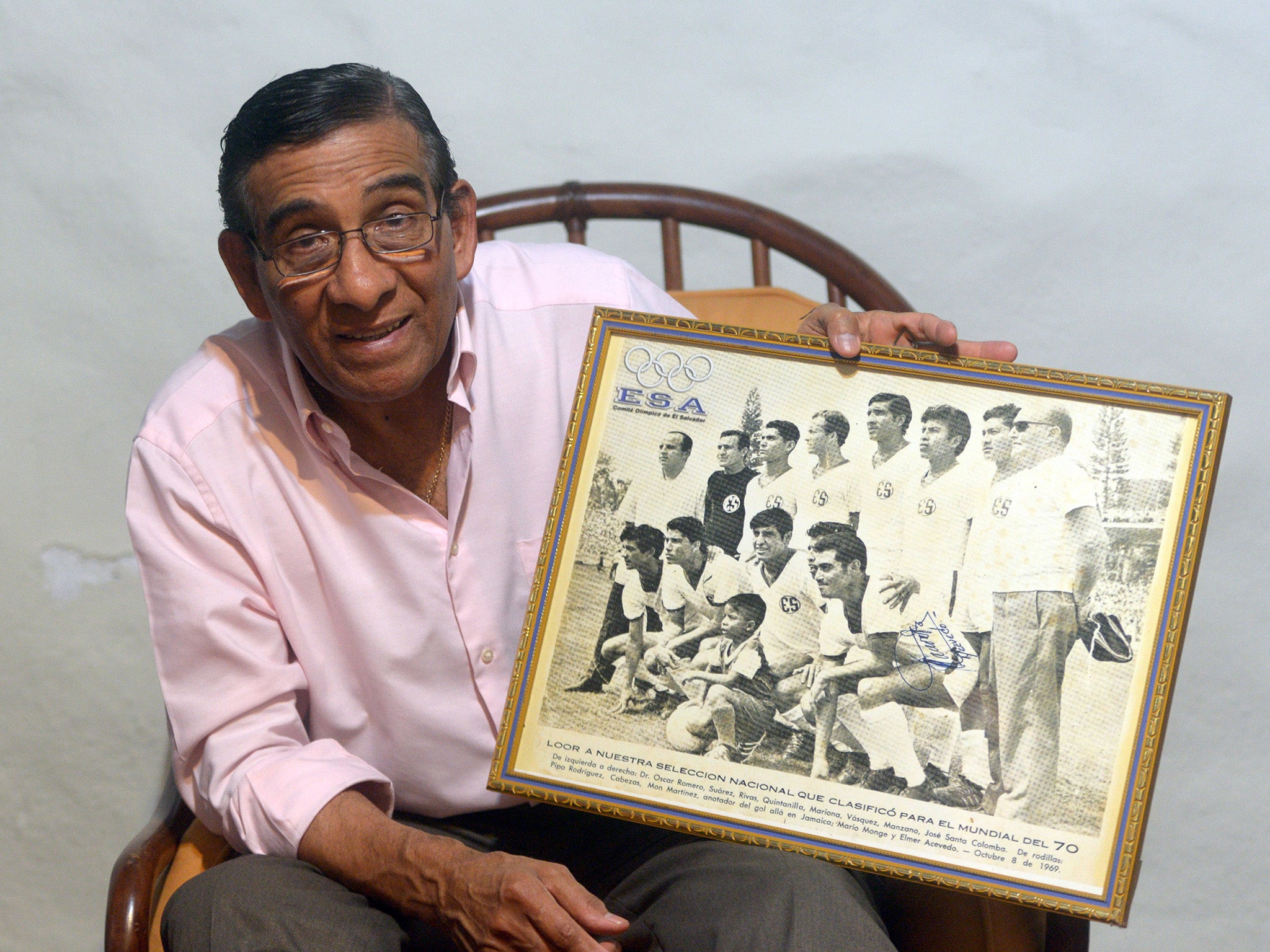

The following summer El Salvador travelled to Mexico for the glorious World Cup, a team with blood on their palms rubbing shoulders with Pele and other football gods. They were beaten by Mexico, Belgium and the Soviet Union; the team scored none, conceded nine and on their return home they all went to sweet Amelia’s grave to sit with the broken-hearted teenage girl who launched a 100-hour football war.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments