When East Germany met West and caused one of the greatest World Cup shocks

East Germany 1-0 West Germany: At the 1974 World Cup, Hamburg played host to an extraordinary meeting of two rival sides. The result was even more unbelievable, writes Adam Bushby

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Arriving at Hamburg airport in their matching light grey jackets, green shirt and yellow ties, the East Germany squad and management team were all smiles. The departure to their camp in Quickborn was delayed when a replacement bus needed to be found as the one emblazoned with “DDR” (Deutsche Demokratische Republik) and flag designated to pick them up went ‘missing’. Given West Germany didn’t even recognise the DDR as a proper country — the national tabloid Bild even referred to the East in inverted commas — this was hardly a surprise. No doubt the slight was documented in forensic detail by one of tourists.

At their base for the first group stage, agents of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany’s Ministry for State Security, better known as the Stasi, among the entourage relaxed their surveillance a touch, presumably overawed by the chance to sample some of the pleasures of the West. With this new-found freedom, a trip to the Reeperbahn was organised by the owners of the Sporthotel in Quickborn. A night on the tiles beckoned. The West German hosts even offered everyone from the East German delegation a free TV. The officials declined — fraternisation with the West was a strict no-no, more so the receiving of illicit Western goods — but some of the players noticed that all the televisions were gone by the time they left.

A 2-0 win over Australia in the East Germany’s first ever game at a World Cup finals was followed four days later by a 1-1 draw with Chile in their second. A somewhat unexpected scoreless draw between their first two opponents, mere hours before kick off, had meant that the pressure was off by their third. Both West Germany and East Germany had already qualified for the knockouts, just leaving the thorny issue of the most politically charged football match of all time to traverse.

Coaches of the DDR-Oberliga teams were invited to attend the all-German clash, but Hans Meyer, coach of Carl-Zeiss Jena, was notable by his absence. “On the day, I had stomach pains and had to stay home,” Meyer later recalled. Meyer is well-known in Germany for his sarcasm and irony — he certainly wasn’t ill on the day of the game. He had turned down the offer on the grounds that he had to catch a train from Gera at 4am, then “travel with the fans to Hamburg, wave my hammer and sickle flag, get stared at by the other fans like some exotic creature, get straight back on the train after the game, and then get back home in the middle of the night”. He saw straight through the absurdity of the situation and presumably watched the game at home, ohne flag.

It wasn’t a harmonious build up to the finals for the 1974 World Cup hosts, and favourites, by any means either. West German authorities wanted to avoid a repeat of the shocking violence of the Munich Olympics two years earlier when the Palestinian militant group, Black September, murdered five Israeli athletes and six coaches. The Chilean consulate in Berlin was fire-bombed shortly before the finals began so the South Americans trained on a pitch surrounded by barbed wire, while Scotland had concerns over the IRA and there were also very real fears that the Baader-Meinhof gang were planning something big after a threatening letter announced that the Volksparkstadion would be blown up. That security at the finals was beefed up in response was an understatement. The West German base camp in Malente, to the north of Hamburg, resembled a “fortress”, according to Paul Breitner.

Looking beyond the barbed wire, the guard dogs and the armed guards, it’s no exaggeration to say that on the day of the game itself, the day one half of Germany would meet the other, West Germany expected two points to be served with the largest piece of cake this side of Hamburg. “Warum wir heute gewinnen” screamed the headline of the tabloid Bild’s front page. “Why we will win today”.

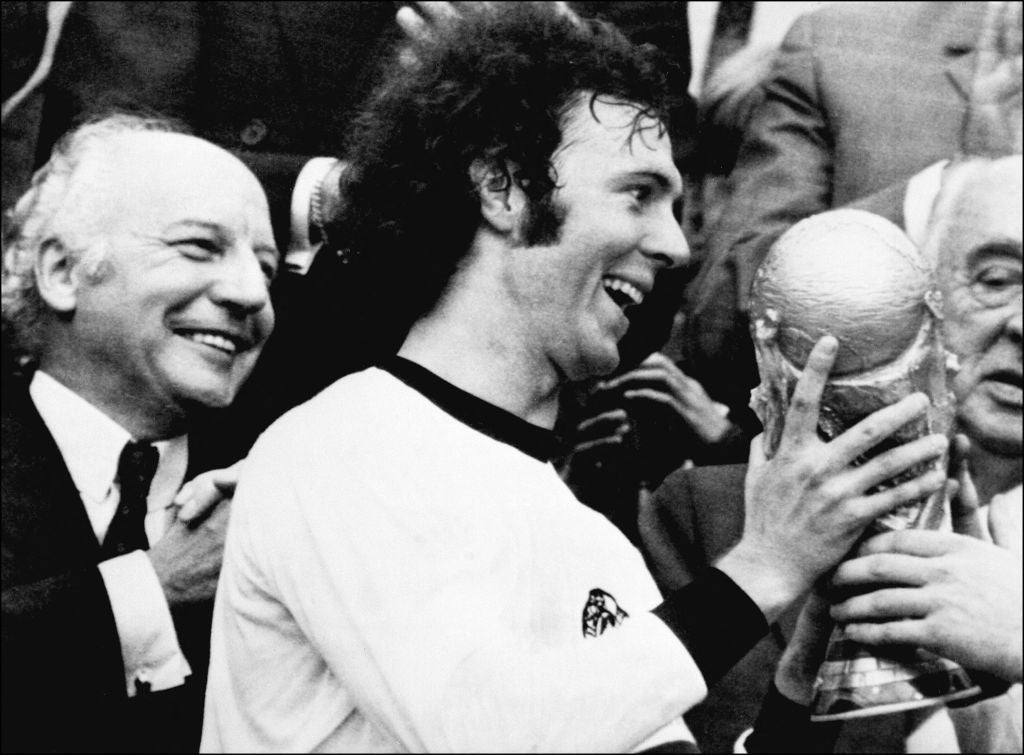

The optimism in West Germany had not been backed up by performances on the pitch, however. They had stuttered to a 1-0 win over Chile that was greeted by catcalls from the home fans in West Berlin’s Olympiastadion. A 3-0 victory over Australia in the second match again failed to thrill the watching public. The composure associated with captain Franz Beckenbauer deserted him when he gave away possession and was booed by the West German crowd. Der Kaiser spat in disgust in the direction of the hisses.

Nor was all well behind the scenes in Malente either. A few days before the tournament, a dispute over player bonuses had seen manager Helmut Schön pack his bags and threaten to leave the camp altogether. So too had left-back Breitner, who was convinced to stay by Günter Netzer, Gerd Müller, Wolfgang Overath and Uli Hoeneß. Meanwhile, Beckenbauer was negotiating over the phone with DFB vice-president Herman Neuberger to raise the World Cup-winning bonus from DM30,000 per man to DM100,000. They would eventually settle on DM70,000 but not before Schön had berated his players. “All I ever hear from you is money, money, money!” It was a mess.

Not that it should come as a surprise that Schön was a little highly-strung in the build-up. The manager was born in what would become East Germany and had managed in the Soviet-occupied East until overwhelming political interference made his position untenable and he fled to the West. As Uli Hesse explains in the brilliant Tor!, the West Germans “knew their Dresden-born coach wanted — no, needed — to win this match at all costs”. All eyes turned to Hamburg.

Chants of “Deutschland, Deutschland” rang around the stadium before kick-off, though the choir didn’t include the 1,500 hand-picked, East German apparatchiks; they seemed content with waving their little flags — black, red and gold ones embossed with hammers and compasses. Müller rolled the ball to Wolfgang Overath and a game for the history books got under way.

West Germany dominated the early chances but although the floodgates might have creaked a bit, it wasn’t all one-way traffic. A better first touch by Gerd Kische after being set free by Hans-Jürgen Kreische may well have seen East Germany get their noses in front. Kreische then missed an open goal from close range before tehe West replied, with Müller hitting the post. It was goalless going into the break, and remained so by the 78th minute. Enter our hero.

The most significant goal of the 1974 World Cup began with a long diagonal into the path of Jürgen Sparwasser. Using the element of surprise, Sparwasser opts to control the pass with his face, a move of deceptive finesse. He races diagonally from left to right, past both the flat-footed Horst-Dieter Höttges and Berti Vogts. He arrows towards Sepp Maier’s goal … he can’t … can he?

“Sparwasser.”

Another touch away from Höttges and Vogts …

“Sparwasser!”

He has to shoot.

“Und …”

Shoot man, shoot!!

“Tor!!!”

He has you know!!!!

Sparwasser arrows the ball over Maier into the roof of the net and with it secures one of the great World Cup upsets. It is when watching the goal in slow motion from behind Maier’s goal that the deftness of Sparwasser’s shape to shoot can be appreciated. Imperceptible at first, he cocks his right leg back but holds off connecting for a split-second, long enough to sit Höttges on his arse and daring Maier to commit to a dive, which he does. Bang!

Sparwasser does a tipple tail then wheels away like a puppy chasing a roll of toilet paper. “Never before in my life have I done a somersault,” he would later say. He ends face down on the turf on the touchline, surrounded by his ecstatic teammates, overcome with the emotion of it all. Now it is cries of “Heja, heja DDR!” that ring crisply through the still night air.

"Following the final whistle, all the players swapped shirts, although we didn’t do it on the pitch because officially it was forbidden," Kreische remembers. “But we got on very well. We spoke the same language after all. It was a hard but fair battle.”

‘Spoke the same language’. Let that hang in the air for a few seconds. German was the first language of both Germanys. This game pitted Germany against Germany. In the World Cup. One saw the other as an aberration, while one saw the other as the enemy. And that’s really quite astonishing when you think about it.

Against All Odds: The Greatest World Cup Upsets is available to buy now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments