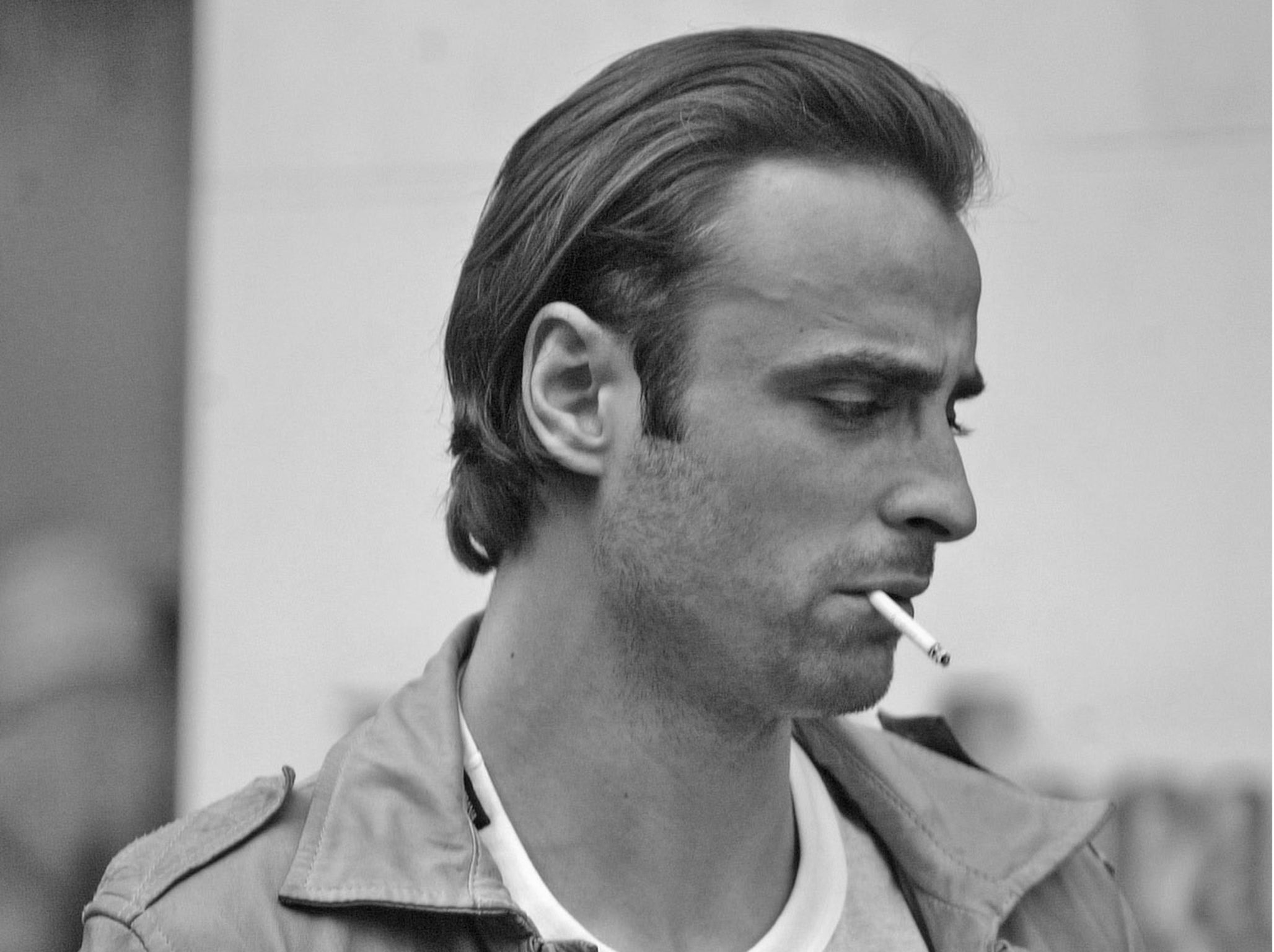

Premier League 100: Why there have been few players as misunderstood as Dimitar Berbatov

At No51 in The Independent's 100 greatest Premier League players is Dimitar Berbatov, an enigmatic genius whose star burnt brightest during his two seasons at Tottenham Hotspur

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The smuggled cutlery was among the first signs that Dimitar Berbatov was more than a little bit different. The Bulgarian had only been at Tottenham Hotspur for a matter of days when he began rummaging around in the club canteen, searching for something. “He used to come to the training ground with his own knife and fork,” his former team-mate, Mido, later recounted. “He used to get a knife and fork out of his pocket and eat. And we all used to think: ‘What is that? What is going on?’’

It was a good question, one that followed Berbatov throughout the eight years he spent strolling around Premier League pitches with all the lofty indifference of a landed gent exploring the outer reaches of his estate. ‘What is going on?’ Defenders would ask it after he had ghosted past them. Fans would ask it after another middling performance marked by a wonderful goal. And coaches would ask it, again and again, after the misanthropy, melancholy and mood swings.

No player in the 27 year history of the Premier League has been as misunderstood as Dimitar Berbatov, both on the terraces and in the dressing room. Some thought he was aloof. Others thought he was arrogant. But at least everybody could appreciate his class: the goals, the vision and one of the finest first touches we have ever seen, the ball never far away from sticking meticulously to his blue-tac blob of a right boot.

It did not help his case that he made a slow start to his new life in England. In 2005/06 he scored 24 goals for Bayer Leverkusen, drawing dewy-eyed scouts from across Europe to North Rhine-Westphalia. A £10.9m move to Tottenham — a club Berbatov would later confess to not having heard of — was agreed, but he struggled in his first few matches for the club: “The worst player on the pitch” in the words of Mido.

His consciously restricted work rate was one distinct early worry. But what did Spurs expect? You do not pay £100k short of a club-record fee for a workhorse. Berbatov’s brilliance was instead defined by an artisanal elegance and the complete elimination of any superfluous movement. No high press. No dropping deep to assist the defence. Certainly no chasing after lost causes. And for good reason. His managers would eventually stop demanding such things for the same reason nobody ever asked Jackson Pollock to paint between the lines.

Before long there were goals. Lots of goals. He was up and running with a tap in against Sheffield United, beginning to score regularly from November onwards. There were thumping volleys against Reading and PSV. A floated free-kick against West Ham. An ice-cold penalty against Chelsea at Wembley. And a sublime finish against Braga that encapsulated his entire approach in the blink of an eye: a flick, a whack, a shrug. You don’t need to sprint until blue in the face if you can read the game like a storybook. You don't need multiple touches if you have the skill to only take two.

On YouTube, the goalscoring compilations of most players are soundtracked by brash Europop or pounding drum and bass. Berbatov’s is set to The Cinematic Orchestra's sweeping ballad, “To Build a Home”.

Key to his turnaround at Tottenham was Martin Jol’s decision to pair him up front with Robbie Keane. It did not matter that they were strange bedfellows: Berbatov with his statuesque poise, Keane with his fraught kinetic energy, forever starting and stopping, bobbing and weaving, moving, moving, moving. “You ran for both of us and talked for both of us,” Berbatov told the Irishman upon his retirement. When the duo helped Spurs to League Cup success in 2008, Keane pulled on a cap and bells while glugging from a Carling bottle, as Berbatov sauntered around in the background with a wry smile and on-brand arched eyebrow.

And yet for all of Keane’s dynamism and drive, there could only be one leading man. And there was never any doubt that Berbatov, who eschewed Duolingo and Babbel in favour of learning English by watching gangster movies, was Tottenham’s very own Vito Corleone. Their Don. Their Godfather. “When he is not the centre of attention and main man, he is grumpy,” his brother, Asen, conceded towards the end of Dimitar’s time at Tottenham.

But beneath the theatrical swagger and sadness, something more complexed lurked. “Nothing is what it seems with Dimitar,” the manager who knew him best, Jol, once revealed. “And depressed people, they can be very cheerful but people don’t notice. But I think there is nothing wrong with him. Sometimes it’s a pose as well. He doesn’t want to work his socks off because that’s not him.”

Centre stage can be a lonely place to be, especially for a man who may have craved attention only to often react awkwardly to it. “I didn’t like it,” he once remarked of hearing Spurs supporters singing his name. “Some players do, but I was embarrassed and thinking: ‘Please, please shut up.’” Before long Jol was sacked, replaced by Juande Ramos, with Spurs finishing eleventh in the league. Berbatov pushed for a £30.75m move to Manchester United and the two-season love affair was over. Daniel Levy replaced him with Frazier Campbell.

Perhaps this contradiction at the core of Berbatov’s personality can explain why his ensuing spell at United was not perceived to be as personally successful, despite close to fifty Premier League goals, two league titles and a memorable hat-trick against Liverpool at Old Trafford. Jostling for position with Cristiano Ronaldo, Carlos Tévez and Wayne Rooney, his time as a leading man was over. He was never a system player. He was never an impact substitute.

In his autobiography, Sir Alex Ferguson writes illuminatingly of how Berbatov’s presence began to wane. “Berbatov was surprisingly lacking in self-assurance,” he conceded. “He never had the Cantona or Andy Cole peacock quality, or the confidence of Teddy Sheringham… Berbatov was not short of belief in his ability, but it was based on his way of playing. Because we functioned at a certain speed, he was not really tuned into it.”

After four seasons in Manchester, Berbatov would end his time in the Premier League by returning to London and reuniting with Jol, this time at Fulham. Reinstated as the main attraction he quickly rediscovered the scoring touch that had started to abandon him during his final season at Old Trafford, equalling his second most prolific season in English football. But old habits die hard. “He just didn’t really talk to anyone, you’d walk into a room and he’d be sitting there and he wouldn’t lift his head,” one team-mate, Mark Schwarzer, recollected. “You’d go ‘Morning Dimi’ and he’d just grunt at you. He never ever opened up, you could never find out more about him.”

His final season in the Premier League then mirrored his first: a man determined to play the leading role but with little to no interest in the superficiality of all that surrounds it. To the end, Berbatov was plagued with accusations of nonchalance and laziness, yet craved responsibility despite his aversion to adulation. Does that not show his maturity? Does that not show his selflessness? There have been few Premier League players as fundamentally misunderstood, before or since.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments