Paul Pogba, Pep Guardiola and the evolution of leadership in the modern game after penalty debacle

Man United appeared to lack leadership when Pogba and Marcus Rashford discussed who should take the spot kick vs Wolves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is a wish so often heard in the stands and, at clubs like Manchester United and Arsenal of late, occasionally heard among the staff themselves. More than anything, it is of course only ever heard when things aren’t going well.

“This place needs some proper leaders,” as some at Old Trafford have literally said over the last few years, not least at Molineux on Monday.

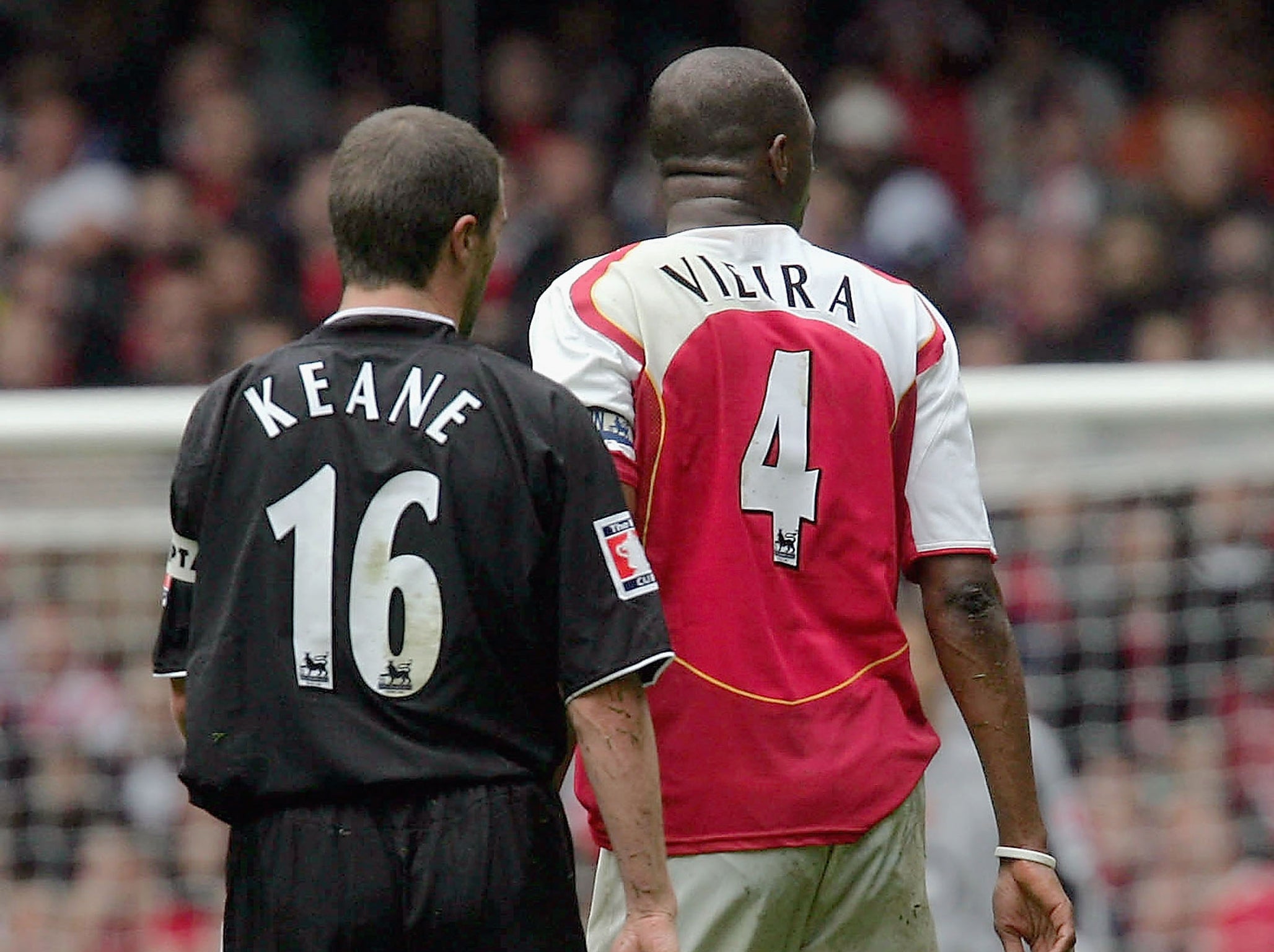

The instigation there inevitably involved one of those players often considered well short of such standards, as Paul Pogba took the ball of Marcus Rashford for that controversial missed penalty. Many around the club were only too willing to point to a contrasting incident from 2002, when United were 3-0 up in an easy Champions League qualifier against Zalaegerszeg, and a penalty was seen as the perfect opportunity for the misfiring Diego Forlan to end a drought at the club.

Well, it wasn’t seen that way by everybody.

Roy Keane had no time for such indulgences, and forcefully insisted that the usual rules must still apply. He grabbed the ball off Forlan and handed it to regular penalty-taker Ruud van Nistelrooy. That was that.

From that little memory, it was a natural leap for many to wonder how the current dressing room would react to a leader like Keane; how he’d straighten things; what his effect might be.

The answer, however, may not be as positive as usually imagined.

Except you don’t really have to imagine. There’s already precedent. A squad as limited in status as Ireland’s didn’t really take to Keane’s approach when he was assistant manager. Many thought it was a bad joke, and old-hat. A much higher level group like United’s would likely have an even lower tolerance for it.

“The modern player just wouldn’t have it,” one source who has worked at a top-six club says.

This isn’t to single out Keane. It applies to pretty much any old-style hard-edge ‘leader’ you can think of, from Tony Adams to Graeme Souness, and reflects a wider change in the game.

That style just doesn’t really exist any more, to anything like the same level.

There is no better reflection of this change in prevailing mood than through the change in the dominant team.

At the very height of Sir Alex Ferguson’s United empire, one of his great abilities was an appreciation for delegation, and that didn’t just apply to his staff. He ensured he had big characters as players, who were almost self-policing, and psychologically conditioning certain standards in the team.

Manchester City have largely succeeded in their grand aim of replacing United as the dominant club, but Pep Guardiola has very much not succeeded Ferguson in this approach. He has done the complete opposite. He has mostly got rid of such characters, in a policy summed up by his jettisoning of Joe Hart.

There were obviously a few factors to that decision, not least the goalkeeper’s struggles with his feet, but it is telling that Guardiola saw no use for Hart’s famed “impact on the dressing room”.

The Catalan didn’t want any such characters diluting his authority. All of the power was centralised around the manager, and the ideas he put in place.

Jurgen Klopp and Mauricio Pochettino operate in the same way, if to different degrees. You only have to consider how the Argentine looks to get rid of any player who shows the merest hint of dissent. Even Tim Sherwood, often wrongly seen as exactly such an old-school character, views it like this. “This is the modern game,” he remarked.

Some of this is obviously down to the psychological development of the modern player. They have been brought up a world away from the hard-edged hazing and bollocking culture that forged decades of players, and ensured only the most resilient survived.

Just as much of it, however, is down to the football development of the modern player.

The “leader culture” naturally ruled in a sport that was much more free-form than it is now, that involved much less collective co-ordination, and basic tactical structure. As recently as 15 years ago, for example, those at the top levels of hockey used to marvel at how unsophisticated football was in terms of organised pressing. It is little wonder that the strongest-willed individuals had much more influence in such an environment, or that managers saw the importance of bringing them in. There was a need for players who just “knew” what to do. Football was much more instinctive.

That has drastically changed in the last decade. Guardiola’s own 2008 reimagining of pressing, and its drastic spread and evolution through coaches like Klopp, has dramatically changed the very coaching of the game as much as the actual football. Academy graduates aren’t just taught how to play. They are taught how to use space and position relative to their teammates, how to move. They are tactically educated. Those who know Raheem Sterling cite this deeper understanding of space as a major reason for this resounding improvement in his game, transforming him from a winger who “largely moved in straight lines”.

“There is just so much to learn” for the modern player, as Sterling’s famous current manager so often states.

In the midst of that – and tactical instructions that for the first time in football’s history can rival the type of plays an NFL quarter-back has to study in terms of their elaborateness – one angry “leader” ranting away has much less effect. It is much less important, especially in polyglot dressing rooms.

One Premier League coach even privately argues how a team that “needs leaders” is really just a team that is “badly coached”.

The bottom line is you don’t need big characters when you have a big idea; a proper playing identity.

This is what has really changed. The system subsumes all. Team identity is more important than all.

Everything follows from that.

This is not to say that absolutely everything has changed, not least as regards standards. Keane was still right on that penalty incident. He and figures like Adams would still have been great players in this era. Dressing rooms will still occasionally need hard truths, and always need assertion.

True “personality” in football remains the same, too: the courage to get on the ball, to play it assertively rather than safely, to keep going after a mistake.

But the idea of what “leadership” is has changed.

This is what Gareth Southgate has tried to drum into his England squad, with a “leadership group”. This is why Harry Maguire is seen as part of that, and is so good for this Manchester United team. He is a very modern leader in the sense he is diligent, and responsible.

This is one reason Arsenal have bought David Luiz, and similar is said of Jordan Henderson at Liverpool.

These players are seen as “glue”, and are much more effective in the modern game in terms of fusing teams than the welders who used to use the fire of their personality.

These days, that’s a much better route to getting what everyone really wishes for: how to win.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments