Jurgen Klopp beware - the numbers don't always add up at Liverpool

FSG’s reliance on analytics to assess players has led to some expensive mistakes and contributed to Brendan Rodgers’ sacking

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Don’t expect Jürgen Klopp to have all the answers about how to stop Liverpool throwing money around like confetti on players who vanish without trace. He vetoed Borussia Dortmund’s purchase of Bayern Munich’s Mario Mandzukic last year because he and the striker had clashed during a match. It was to prove a costly mistake. He signed Ciro Immobile from Torino for £14m instead. Dortmund stopped scoring, Immobile bombed and was offloaded to Seville on loan.

The Dortmund buying method does not generally fail. It entails Klopp, his trusted friend Michael Zorc – a former Dortmund player with whom he has been known to holiday and from whom he once received the gift of a pet dog – and the Dortmund chief executive Hans-Joachim Watzke, all having to be unanimous. Robert Lewandowski (£3m from Lech Poznan) and Shinji Kagawa (£300,000 from Osaka, sold to Manchester United for £18m) prove they can call the big ones right.

But simplicity is not something Klopp will encounter at Anfield, where the first obstacle he will face when the euphoria of his introduction has subsided will be the club’s deep attachment to the theory that players’ statistics – analytics – can provide most of the answers in the market.

The philosophy was only to be expected when the club entered into the ownership of John W Henry, who made his millions by using hard data to play the futures markets and getting the edge on those prepared to rely on instinct. But what began as a significant tool has become an intrinsic part of how Liverpool operate.

Damien Comolli, known as the metrics king when hired as director of football by Henry, was wise enough to accept the scout’s intuitive feel, not least because there are no analytics on very young players. He backed the judgement of Liverpool’s Academy in 2011 to spend £200,000 on Jerome Sinclair, one of the great young hopes, and £1.5m on the 14-year-old Sheyi Ojo, currently on loan at Wolves. It was on the basis of what the scouts saw that, despite managing director Christian Purslow’s reservations, they spent big on Raheem Sterling (£400,000) in the last year of the Rafael Benitez era. Liverpool backed their judgement.

But Comolli’s departure and Brendan Rodgers’ arrival as manager, two months later, coincided with analytics assuming greater significance. Mike Gordon, one of Henry’s early Boston Red Sox business partners who is now running the Liverpool side of FSG’s business, discovered Ian Graham, a football specialist at Decision Technology, a British data collection firm being paid for their research by Tottenham chairman Daniel Levy at the time. The two struck up a close relationship.

Gordon’s interest meant that the executive Liverpool had already signed as head of performance analysis, Michael Edwards, became an increasingly important part of the Liverpool set-up.

Where once Graham was the man with the answers for Gordon on data, Edwards is now the Anfield authority with the Americans’ ear. When Rodgers agreed to share control of transfer policy with Edwards, Gordon, chief executive Ian Ayre and two men hired from Manchester City as head of recruitment and chief scout – Dave Fallows and Barry Hunter – he found himself signed up to the numbers.

The analytics propounded by Edwards saw some very big claims for some very average players. Oussama Assaidi was one of the first sources of excitement, arriving from Morocco in 2012 with some of the best stats Liverpool had known. He started four games and is now playing in Dubai.

Spaniard Iago Aspas’s figures were even more impressive. “The club were mad on him,” says one source. Brentford, where owner Matthew Bentham is another devotee of analytics, privately complimented the club on their purchase. Aspas (outlay: £9m) played 14 games in two years, did not score and is now back where he started, at Celta Vigo. Steven Gerrard flinched at the sight of Aspas, with the body of a little boy who “looked about 15” as he describes him in his autobiography, going up against John Terry and co.

Mamadou Sakho (£12m) was another whom Edwards – “Eddie” as he is happy to be called – urged Liverpool to buy on the basis of the numbers. There was talk within the club in 2013 of the player being “not just the best defender in England but in Europe”. It was the manner in which he plays – his shakiness – which always gave Rodgers cause for concern.

The numbers cannot tell a club how a player will adapt to England. Liverpool’s Academy staff were convinced in the Benitez era that the Spanish attacking midfielder Suso was a good buy but when he made it to the fringes of the first team they found him mentally weak, dropping down a notch when he thought he had made it. He had a poor diet and was a poor professional. By the time Rodgers realised that the numbers game was killing him, it had become entrenched as Anfield orthodoxy.

Fallows, who is widely respected, does not appear to have challenged it, having arrived with Hunter to put to work the same Scout 7 software they used at City. Hunter, Rodgers’ Northern Irish compatriot, is thought to have a better relationship with Rodgers but had a foot in both camps of what became a political struggle. FSG took a very dim view of Rodgers challenging Edwards. They view him as part of a support system, put in place to help the manager.

Klopp will require someone at board level with expertise in the transfer market if he is to avoid being confronted with the same philosophy and sub-standard players. City’s model – a director of football with experience of playing and buying at the top level, Txiki Begiristain – is the ideal.

Evidence of how FSG lack the expertise still abounds. It was there in their equivocation about whether Klopp was the right man. They were being told he was not four weeks ago, before belatedly starting to make inquiries of their own. It was there in Gerrard’s autobiography when he disclosed that the pursuit of new acquisitions entailed him being asked to text targets and ask: “Fancy joining us?” It was also there in FSG proposing to install Louis van Gaal above Rodgers as director of football in 2012 – something the manager refused to accept. The Dutchman actually has a negligible track record in the transfer market because he prefers to develop young stars instead.

There are no signs that Henry and his associate Tom Werner, Liverpool’s chairman, are tiring of analytics, despite a poor run. There were hints of change when they recently fired Ben Cherington, an avowed analytics man, as Red Sox general manager and replaced him with Dave Dombrowski from the Detroit Tigers – who is not. But he has maintained the analytics and pursued a new line based on the physics of the velocity of pitches thrown, balls hit and how fast the ball spins.

The difference with the baseball is Henry’s proactive involvement. His own belief that you should not pay out for pitchers over 30 – because they lose pace and get injured – saw the Sox sell John Lester last year and buy several average replacements on the basis of their high ground-ball rate stats. Those new pitchers all bombed.

Klopp’s high pressing game will require a huge physical contribution. “The players don’t know what will hit them,” says one source. That means January may be busy. And so it starts again. Only when FSG decide on a football philosophy and employ a board director with expertise of elite-level football will Liverpool put upheaval and a maverick theory in the past.

When stats go wrong: FSG’s poor purchases

Mamadou Sakho

Position: Centre-back

Cost: £18m from Paris Saint-Germain in 2013

Appearances: 47 (four as sub), nine clean sheets

Oussama Assaidi

Position: Winger

Cost: £2.4m from Heerenveen in 2012

Appearances: Six as sub, no goals

Sold to UAE Arabian Gulf League side Al-Ahli Dubai in January for £4.7m

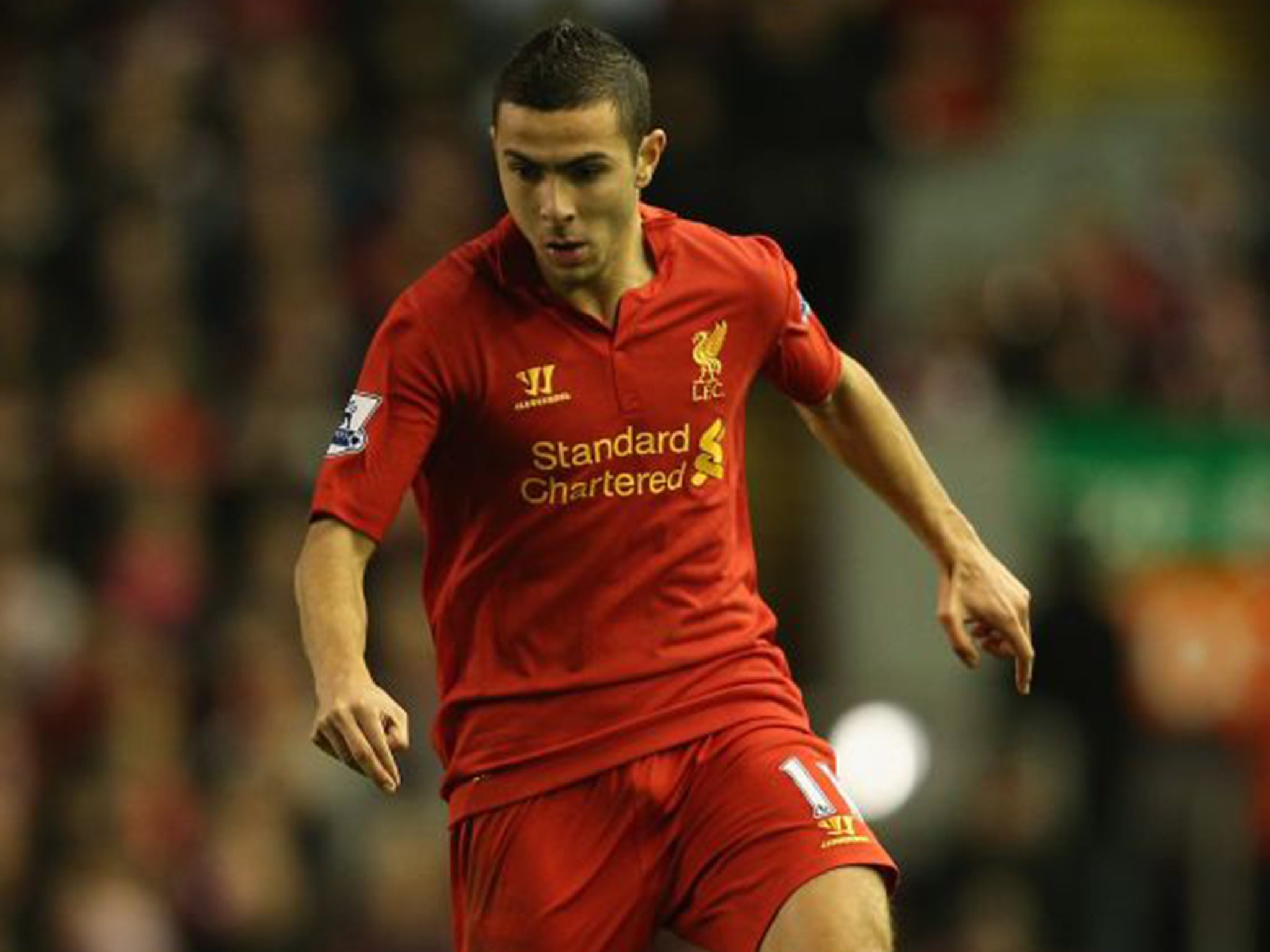

Iago Aspas

Position: Forward

Cost: £7.2m from Celta Vigo in 2013

Appearances: 15 (nine as sub), one goal

Sold back to Celta Vigo in June for £3.5m

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments